Preserving cultures and protecting wildlife

Updated: 2013-11-10 07:59

By Remy Scalza(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

For nearly two decades, Namibia has been part of an ambitious experiment in both community tourism and wildlife conservation, known as communal conservancies. "The idea was to fight poaching by restoring control over wildlife to the local people," said John Kasaona, the director of Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation. "We wanted to show them that they could benefit financially from keeping these animals alive, in particular from wildlife tourism."

The plan has been a resounding - and rare - success story for African wildlife. Seventy-nine conservancies now cover 20 percent of Namibia. Populations of desert lions, desert elephants and black rhinos, all threatened with extinction in the '90s, have increased several times over, while poaching has plummeted.

At the same time, the conservancies have teamed up with tourism operators, giving travelers unprecedented access to animals and local culture.

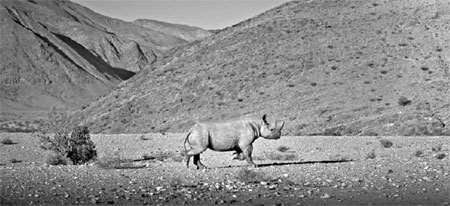

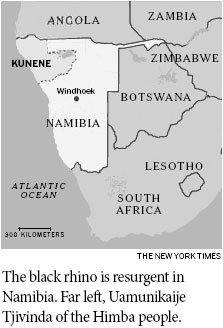

Nearly half of all of Namibia's conservancies, and many of the country's most ambitious community tourism projects, are in the northern Kunene region, an expanse of dry mountains and valleys the size of Greece but with fewer than 90,000 inhabitants. Rutted tracks thread through desert, cross dry river beds and sometimes disappear altogether. There, the conservancies have logged one of their greatest successes, the return of the endangered black rhino.

"These animals were almost completely wiped out by poachers 25 years ago," said Aloysius Waterboer, a guide at Desert Rhino Camp, a tent lodge located in Damaraland, traditional home of the Damara people. Roughly 30 rhinos now live in this area. The camp sits alone on 4,400 square kilometers of rocky hills and desert scrub leased from area conservancies, who are also 40 percent shareholders in the project. Many of the expert rhino trackers on staff are former poachers. "If you're a poacher, all you really want is to feed your family," Mr. Waterboer explained. "So it made sense to put them on the payroll."

At the edge of Kaokoland, in the arid northwest, may be Namibia's most unusual community tourism experiment. The first guest camp owned by the Himba people, one of the country's last truly seminomadic tribes,sits on a mountaintop in the Orupembe conservancy. Opened in 2011, Etambura Tented Lodge is hundreds of kilometers from the nearest village on the electrical grid. Many of its Himba owners reside in the surrounding valleys, herding goats and cattle, and living in dung-and-stick huts, as they have for centuries. More than wildlife, it is these people whom travelers come to see. And unlike tensions with animals, the challenges to isolated tribal communities posed by the conservancy model are just beginning to be acknowledged.

"Wildlife are cared for like our own livestock, and money from tourism goes into our conservancy bank account," said Uamunikaije Tjivinda, a Himba woman, as she threw strips of dried giraffe meat into a pot of boiling water. "The conservancy has been good for us."

"Before the camp opened, there were almost no tourists in this part of the country," said Kaku Musaso, a camp manager brought in from the city of Opuwo who, like many modern Himba women, wears Western clothes and speaks impeccable English with a British accent. "It was rare to see any white people here."

Early one morning, Ms. Musaso guided visitors along a rocky ridge, then down a steep slope to a watering hole. Hundreds of goats clustered around a shoulder-deep depression dug in an otherwise dry river bed, where a young boy was scooping buckets of water into a wooden trough. In the shade of a shepherd's tree, six Himba women and a dozen children gathered.

Like Ms. Tjivinda, many women of the semi-nomadic Himba people have plaited hair that is a striking rust-red color, rubbed with ocher dug from the earth.

The women unrolled blankets and topped them with baskets and jewelry made of beads and ostrich bone. Ms. Musaso bargained and the visitors handed over the equivalent of $20 in Namibian bills. When asked what they used the money for, one woman produced a package picturing a young woman with long, regal tresses: synthetic hair extensions, made in South Africa.

The New York Times

|

Photographs by Remy Scalza for The New York Times |

(China Daily 11/10/2013 page10)