The fate of horses at risk

Updated: 2013-09-01 08:10

By Fernanda Santos(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

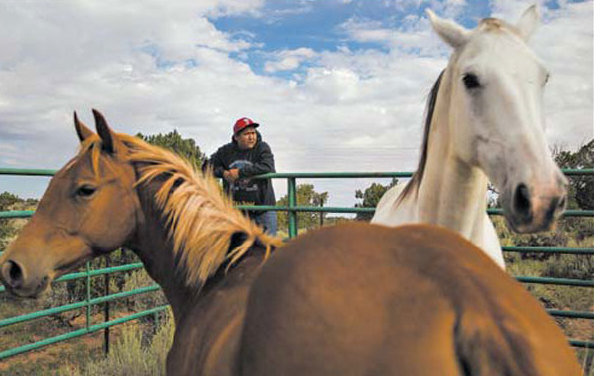

Free-roaming horses cost the Navajos $200,000 a year in damage to property and range. The horses are in competition for water and forage. Photographs by Diego James Robles for The New York Times |

Issue pits Indians vs. stars

It seemed like a logical alliance for the interconnected worlds of Hollywood and politics. Bill Richardson, a former governor of New Mexico, and the movie star Robert Redford joined animal rights groups in a lawsuit to block the revival of horse slaughter in the United States, proclaiming they were "standing with Native American leaders," to whom horse slaughter "constitutes a violation of tribal cultural values."

Soon, though, the two men found themselves on a collision course with the Navajo Nation, America's largest federally recognized tribe, whose president released a recent letter to Congress asserting his support for horse slaughtering.

Free-roaming horses cost the Navajos $200,000 a year in damage to property and range, said Ben Shelly, the Navajo president. There is a gap between reality and romance when, he said, "outsiders" like Mr. Redford - who counts gunslinger, sheriff's deputy and horse whisperer among his movie roles - interpret the struggles of the Indians.

"Maybe Robert Redford can come and see what he can do to help us out," Mr. Shelly said. "I'm ready to go in the direction to keep the horses alive and give them to somebody else, but right now the best alternative is having some sort of slaughter facility to come and do it."

The horses, tens of thousands of them, are at the center of a passionate dispute playing out in court, in Congress and even within tribes across the West about whether federal authorities should sanction their slaughtering to thin the herds. The practice has never been banned, but it stopped when money for inspections was cut from the federal budget.

In Navajo territory, parched by years of unrelenting drought and beset by poverty, one feral horse consumes 20 liters of water and 8 kilograms of forage a day, some of which the Indians need for their cattle.

There are 75,000 feral and wild horses in the United States, Mr. Shelly said. They have no owners,

and many are believed to be native to the West. The tribes say they must find an efficient way of reducing the population. Although it is common to shoot old horses, there are too many of them to be dealt with, and there is money to be made rounding them up and selling them.

There is also the question of sovereignty, one of the points raised in a resolution endorsing horse slaughter that was issued by the National Congress of American Indians, the oldest and largest organization of American Indian and Alaska Native tribal governments.

Citing hillsides and valleys denuded by overgrazing by feral and wild horses, which on reservations throughout the West "are nearly everywhere you look," the resolution accuses the federal government of failing to consult the tribes before proposing language in the Agriculture Department's appropriations bill to again withhold money for slaughterhouse inspections.

Mr. Richardson acknowledged the conflict, which has sown divisions even among members of the same tribe. The plaintiffs in the lawsuit include tribesmen who spoke of American Indians' special relationship with horses, "the magnificent four-legged" animal "who has a part in our creation stories," as Paul Tohlakai, a Navajo, put it.

"Institutionally," Mr. Richardson said, "there have to be some issues that have to be dealt with, and that's why the ultimate solution is to find a natural habitat, or a series of natural habitats, and adoption for the horses."

The United States has never fostered a market for horse meat, a dietary staple in places like Belgium, China and Kazakhstan, but at one point, there were more than 10 slaughterhouses. The last three closed in 2007, after Congress banned the use of federal money for inspection of the facilities, which effectively ended the practice since they don't receive the government's seal of approval.

In their last year, the three plants slaughtered 30,000 horses for human consumption and shipped an additional 78,000 for slaughter in Canada and Mexico.

Wayne Pacelle, the president of the Humane Society of the United States, said the group's efforts were focused on preventing the killing of horses for human consumption "to avoid creating an industry that would turn horses into a global food commodity."

Mr. Pacelle said there were alternatives to slaughter, like using contraceptives to control the horse population.

For Mr. Shelly, his question has been whether it is better to slaughter free-roaming horses or, as many on the Navajo reservation have done, let them die slowly of thirst and disease.

The New York Times

(China Daily 09/01/2013 page9)