Nobel winner touting cell test

Updated: 2013-04-21 07:50

By Denise Grady(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||

|

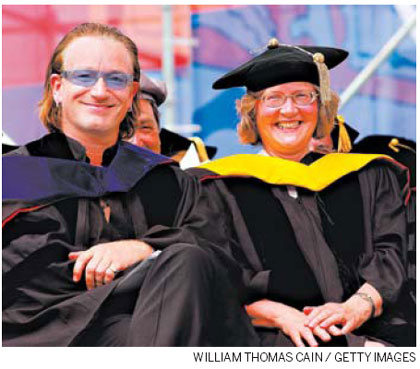

Elizabeth H. Blackburn says data links the size of telomeres, bits of DNA that keep cells from aging too soon, to disease. Dr. Blackburn at the University of Pennsylvania in 2004 with U2's lead singer Bono to receive honorary degrees. |

SAN FRANCISCO - Elizabeth H. Blackburn considers herself a skeptic. But she admits to impatience at times with the questions some scientists have raised about one of her ventures.

At issue is a lab test that measures telomeres, stretches of DNA that cap the ends of chromosomes and help keep cells from aging too soon. Unusually short telomeres may be a sign of illness.

Dr. Blackburn, who shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in medicine for her work on telomeres, thinks measuring them could provide a chance to intervene early and even prevent disease. A company she helped found expects to offer measurement tests this year.

Other researchers have raised doubts about the usefulness of the measurement, which does not diagnose a specific disease.

But Dr. Blackburn, 64, a professor of biology and physiology at the University of California, San Francisco, says she is convinced.

A decade of data from her team and others links short telomeres to heart disease, diabetes, cancer and other ailments, including chronic stress and post-traumatic stress disorder. She has also delved into the connections among emotional stress, health and telomeres.

Telomeres are often compared to the plastic tips that keep the ends of shoelaces from fraying. Scientists had long suspected that telomeres protected the ends of chromosomes, but no one knew how. Each time a cell divides, its telomeres shorten, and if they get too short, the cell cannot divide any more. But in healthy cells, the telomeres were being rebuilt.

At Yale University in the late '70s, Dr. Blackburn deciphered the structure, finding that telomeres consisted of six DNA units, repeated many times. She and a researcher at Harvard University, Jack W. Szostak, determined that an enzyme must be restoring the telomeres. In 1978, Dr. Blackburn moved on to the University of California, Berkeley, and in 1984, Carol W. Greider, a graduate student in her lab, found the enzyme: telomerase.

The three shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2009.

A decade ago, Dr. Blackburn began to collaborate with Elissa Epel, a psychologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies chronic stress. One of their projects involved mothers who were the main caregivers for children with chronic diseases.

"It really resonated with me as a mother," Dr. Blackburn said. "I just sort of felt for these women so much. A very nonscientific reason, if you will, but isn't that an interesting question?"

Compared with the mothers of healthy children, those with sick ones had shorter telomeres and less telomerase, and the longer they had been caring for the children, the shorter their telomeres were. The findings were similar in people taking care of spouses with dementia. Other studies have suggested that traumatic events early in life may have effects on telomeres and health that persist for decades.

These studies, Dr. Blackburn said, have taken her far from her early days as a lab rat, to issues and segments of society that she considers neglected. She has also become curious about the effects of meditation. And she has wondered whether it does anything to telomeres.

People began to ask if their telomeres could be measured. Dr. Blackburn thought it was reasonable to offer a test to the public and helped found a company, Telome Health, in May 2010.

The plan is to begin offering telomere tests, which will require a doctor's prescription, sometime this year. The price will be "competitive," said the company's president and chief scientific officer, Calvin Harley. Other companies with similar tests charge from $300 to $700.

The test does not diagnose a particular disease. Dr. Harley likens it to the "check engine" light on a car - something may be wrong, but more tests are needed to find out what.

"It's not a crystal ball to tell you how many years you've got left," Dr. Blackburn said.

There are ways to protect telomeres, and maybe even lengthen short ones, Dr. Blackburn said. Exercise and a nutritious diet, losing excess weight and easing emotional stress may help.

Some researchers are skeptical, arguing that the associations between short telomeres and illness do not prove cause and effect. Among those who have questioned the test is Dr. Greider, Dr. Blackburn's fellow Nobel winner.

Dr. Blackburn acknowledged that a worrisome result could put a seemingly healthy patient on a path to more tests, prodding and poking.

"You worry about that," she said. "But that's not the fault of the test, is it? That's the fault of the way medicine is practiced. Let's not blame the messenger here."

Dr. Blackburn's hope is that measuring telomeres will become part of a new direction in medicine, geared to what she calls "intercepting" disease.

Unusually short telomeres may indicate a problem, she said, adding, "If you're in the lowest percentile for your age group, you might really be interested in knowing why."

The New York Times

(China Daily 04/21/2013 page11)