Cleaner cooking fuel that saves trees

Updated: 2012-09-09 08:08

By Alice Rawsthorn(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

LONDON - When Sanga Moses was traveling to the tiny Ugandan village where his mother lives, he spotted a familiar figure walking beside the road, carrying a large bundle of firewood. It was his 12-year-old sister, who complained of having had to miss school to walk 19 kilometers to and from the nearest town to collect wood as cooking fuel for the family.

Millions of other Africans, mostly girls, are in the same plight. Mr. Sanga, now 30, was so concerned that he gave up his job as an accountant in the Ugandan capital Kampala and plowed his $500 savings into developing an accessible source of cheap, clean cooking fuel.

As well as saving time and money, it promises to reduce the pollution produced by the fumes of makeshift fuel, and the health problems caused by inhaling them, which are responsible for the death of more than 1.5 million people every year.

Three years later, thousands of Ugandans are cooking with the organic fuel produced by the company he founded, Eco-Fuel Africa, and some 1,500 farmers are augmenting their income by using its equipment to convert agricultural waste into organic charcoal. As well as generating income for those farmers, the system has created jobs for hundreds of other people in selling and delivering fuel and fertilizer. It is also helping to slow the deforestation of Africa, as fewer people now need to forage for wood.

Unlike many other humanitarian design ventures, which were initiated by Western designers in the hope of helping people in developing economies, Eco-Fuel Africa was conceived by people whose friends and relatives are intended to benefit from it.

"The problem I see with most other interventions is that they don't involve local communities enough and are initiated by foreigners who don't understand local problems," Mr. Sanga wrote in an e-mail.

The American design commentator Bruce Nussbaum summed up the problem in a 2010 blog post with the title: "Is Humanitarian Design the New Imperialism?"

From the outset, Mr. Sanga was determined to develop a system that would fit into his customers' existing cooking methods rather than force change upon them.

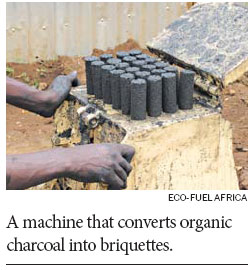

The system begins with the farmers, who collect organic waste and convert it into charcoal in kilns provided by the company. They keep some of the charcoal to fertilize their land, and sell the rest to the company. Eco-Fuel Africa deducts the price of the kilns from their charcoal sales. The charcoal is then converted into briquettes by local distributors using Eco-Fuel Africa's machines. Already some 110 distributors, mostly women, employ local youths to make deliveries.

Mr. Sanga had to sell most of his belongings, including his bed, to pay for the production of the first kiln. Eco-Fuel Africa introduced its first products in November 2010, less than two years after he saw his sister carrying her bundle of wood.

Mr. Sanga is now determined to expand the system, buoyed by Eco-Fuel Africa's selection as a finalist in the 2012 Buckminster Fuller Challenge, which celebrates projects that address "humanity's most pressing problems." The goal is to establish some 200 micro-franchisees next year.

And the more successful Eco-Fuel Africa is, the more money it will generate for another of Mr. Sanga's projects - using part of the proceeds of its sales to plant trees.

The New York Times

(China Daily 09/09/2012 page11)