The role of race in sleeping well

Updated: 2012-09-02 07:56

By Douglas Quenqua(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

|

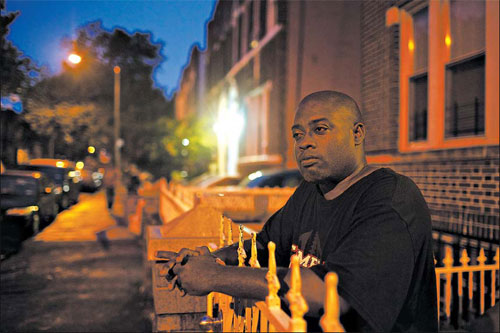

Moleendo Stewart, 41, believes stress from dealing with inequality plays a role in his continuing sleep problems. Benjamin Norman For The New York Times |

Moleendo Stewart can't say for sure what's caused his lifelong sleeping problems. There's the childhood spent in loud, restless neighborhoods in Miami. "You hear people shooting guns all night, dealing drugs," said Mr. Stewart, 41, who lives in Brooklyn, New York. He also cites his weight, 117 kilograms.

Sleep experts would point to another factor: He is a black man.

The idea that race or ethnicity might help determine how well people sleep is relatively new among sleep researchers. In the United States, non-Hispanic whites get more and better-quality sleep than people of other races, studies show. Blacks are the most likely to get shorter, more restless sleep.

What researchers don't yet know is why. "We're not at a point where we can say for certain is it nature versus nurture, is it race or is it socioeconomics," said Dr. Michael A. Grandner, a research associate with the Center for Sleep and Neurobiology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Doctors say that unlocking the secret to racial sleep disparities could show why people in some minority groups experience higher rates of high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes. Helping poor or immigrant populations to get more solid sleep, they say, could also help break the cycle of poverty and disadvantage.

"When people aren't sleeping as well during the night, they aren't as productive during the day, and they're not as healthy," said Dr. Mercedes R. Carnethon, associate professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Illinois.

In a study in June, whites from the Chicago area were found to get an average of 7.4 hours of sleep per night; Hispanics and Asians averaged 6.9 hours and blacks 6.8 hours. Sleep quality - defined as ease in falling asleep and length of uninterrupted sleep - was also higher for whites than for blacks.

While those findings are consistent with earlier studies, this one, led by Dr. Carnethon, adjusted for risk factors like cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea and obesity. Blacks and members of other minorities, who are statistically more prone to experience such problems, still got less and more disruptive sleep than whites.

One obvious remaining culprit, says Dr. Carnethon, is socioeconomics. Because Chicago is still a fairly segregated city, "the blacks and Hispanics in our study were generally living in neighborhoods that are closer to freeways, so you have freeway noise, there's more business noise at night, and there's potentially more crime," Dr. Carnethon said. People in lower-income neighborhoods are also more likely to have multiple jobs or to work odd hours, which can interfere with sleep.

The idea that differences in work and living conditions can explain the racial sleep disparities is a popular one among sleep experts. But studies that have accounted for work and living conditions in racial sleep disparities suggest a more complex reality.

At least one study suggests that socioeconomic factors affecting sleep are highly specific to race and gender. Being divorced or widowed was particularly detrimental to the sleep of Hispanic men, while never being married was more likely to take a toll on Asian men. Asian women lacking in education were more likely to report problems than similarly educated white women. And all men in relationships slept better than single men, regardless of relationship quality; for women, the quality of the relationship was more likely to affect sleep.

"There's an effect of socioeconomics," said Dr. Grandner, a lead author of the study, "but it's not really the economic. It's more about the socio."

One study from 2005 - also taking place in Chicago - measured sleep among 669 participants while adjusting for education, income and employment status. Black men on average still slept 82 minutes less per night than white women, who were found to sleep the best of anyone in the study.

Of course, isolating the real-life effects of social inequality can be tricky. "There are more subtle differences" among people than income and education, said Dr. Kristen Knutson, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and an author of the study. "We had no way to control for stress, and there are social stresses an African-American man might feel that a white man with the same income and education level wouldn't."

Mr. Stewart said he did see discrimination as playing a role in his sleep problems. "As a black person in America, even if you succeed in terms of education, you still have to deal with the inherent inequality of society," he said. "In general it's not a fair thing, and you stress because of that."

Sleep experts refer to this as the "autonomy" problem, and studies have shown it has an effect on sleep. "People who feel they have control over their lives were able to feel secure at night, go to sleep, sleep well, and wake up well in the morning and do it all over again," said Dr. Lauren Hale, associate professor of preventive medicine at Stony Brook University in New York, referring to a study she conducted in 2009. "That's part of the cycle not just for blacks and minorities, but other disadvantaged populations."

The New York TImes

(China Daily 09/02/2012 page11)