Rebuilding the metal boy with a clockwork brain

Updated: 2012-01-08 07:58

By Henry Fountain(The New York Times)

|

|||||||

PHILADELPHIA - What makes an automaton tick?

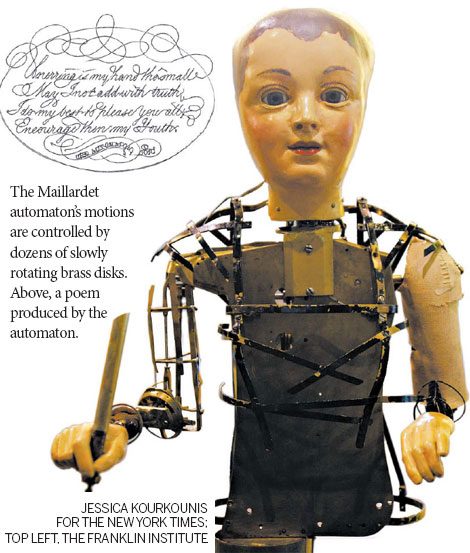

For the one at the Franklin Institute here: a couple of hefty spring motors. A mechanized doll built more than two centuries ago by the Swiss watchmaker Henri Maillardet, it uses power from the wind-up motors to write and draw.

But it is what's between the motors and the arm that makes the half-meter-high Maillardet automaton seem like more than a machine. A stack of rotating brass cams precisely control the arm movements. As steel levers follow hills and valleys cut into the edges of the rotating disks, the arm moves smoothly along three axes - side to side, to and fro, up and down.

The disks are its read-only memory, giving the automaton a repertory of three poems - two in French and one in English - and four drawings, including one of a Chinese temple.

"It's amazing that it does it," said Charles F. Penniman, a retired museum employee who gently tends to the automaton. "But it's really amazing that it still does it after 200 years."

The Maillardet automaton hasn't always done it - in two centuries it has had about as many ups and downs as the undulations on the cams. It was exhibited across Europe for four or five decades, may have been brought to the United States by the 19th-century showman P. T. Barnum, and was damaged in a fire before being donated to the Franklin Institute in 1928. Over the years it's been dressed as a boy (right) and a woman (wrong), and inspected, adjusted, modified and repaired, sometimes poorly.

But these are heady times for the machine: an automaton plays a crucial supporting role in the current Martin Scorsese film, "Hugo," and in the 2007 illustrated novel the film was based on, "The Invention of Hugo Cabret," by Brian Selznick.

Mr. Selznick was inspired by the machine at the Franklin Institute. While working on the book he learned that Georges Melies, the early French filmmaker who is central to the story, had a collection of automatons that was eventually thrown out. Mr. Selznick knew little about the machines. An Internet search turned up references to the Franklin Institute's automaton.

"When I called, that's when I was informed it had broken many years earlier," he said. "And that it was in the basement and out of view."

When Mr. Selznick visited, the Maillardet automaton's head was off, and it could not actually write or draw. But Mr. Penniman was able to wind it up and show him how things moved. "It feels like Charles has this very personal friendship with the automa-ton," Mr. Selznick said.

Mr. Selznick was also instrumental in getting the machine repaired, by Andrew Baron, a designer of pop-up books and restorer of vintage mechanisms in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Mr. Baron came to the museum for several weeks in 2007 and set to work, with the aid of photographs by Mr. Penniman. The automaton, which is part of the museum's permanent "Amazing Machine" exhibition, is now in working order, although it is demonstrated only rarely.

Once wound up and turned on, the machine whirs into action, producing a drawing or poem in about three minutes.

If all goes exceedingly well, it will automatically begin another drawing or poem shortly after finishing the first.

No one knows exactly how automatons of this type were made - trade secrets were common in the early 19th century - but the precision of the work is remarkable.

"It's hard to get a very lifelike, fluid motion of a simple arm movement or hand movement without becoming jerky," said Jeremie Ryder, a conservator at the Morris Museum in Morristown, New Jersey. "Here they were doing it just brilliantly."

Mr. Baron said the movements of the head and eyes, which are controlled by cams, are especially remarkable.

When the automaton stops writing briefly as the cam stack shifts, the head comes up and the eyes gaze out for a few seconds.

"In this moment, he appears to his audience as if he's thinking about what he is going to do next," Mr. Baron went on. "It's performance art."

The New York Times

|

Charles F. Penniman, a Franklin Institute volunteer, tends to the doll. Below, a drawing by the Maillardet automaton. Jessica Kourkounis for The New York Times; Below, The Franklin Institute |

(China Daily 01/08/2012 page9)