Time we changed our development paradigm

Updated: 2007-12-21 07:26

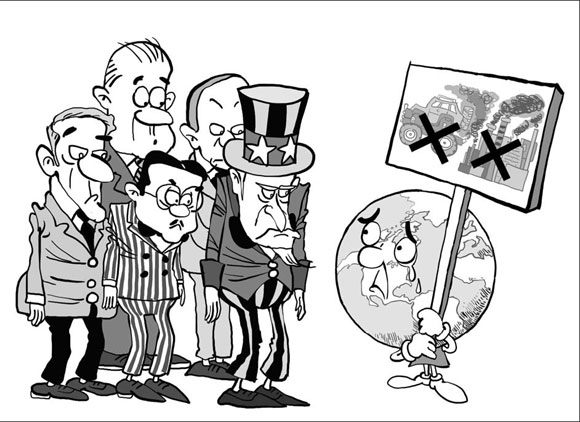

World leaders left Bali this week after debating the future of our planet. Nothing concrete emerged, though, because it will take another two years for them to agree to a post-Kyoto Protocol deal - if they agree at all, that is.

Many a method has been suggested to save the world from the impending catastrophe of global warming. So what's the best way to fight climate change? Carbon trading is the most potent weapon the West has developed to green our valleys and blue our skies. But what is this carbon trade?

The conflict between industrial development and the environment was first recognized in the early years of the last century. But pollution then meant what the eyes could see and the nose could smell. Clean air became a big issue in the 1960s and the 1970s.

But by then the world had discovered a far greater threat to life: the hole in the ozone layer. We panicked because we could all die of radiation. Many studies later, however, it was declared the hole was above Antarctica, so the rest of the world (that is, the entire human race) need not worry. Let the icy continent suffer.

By then, nevertheless, the world had realized something was seriously wrong with the way it was trying to make life more comfortable for those who could afford it. What was it? Chlorofluorocarbon - used in refrigerators, spray cans and air-conditioners. It was banned. We thought the world had stopped using it, and we heaved a sigh of relief.

So far, so good - but not as good as it gets. Nature was acting strange. The air had not cleared after all. Something called greenhouse gas (GHG) was responsible for the damage to the environment, we discovered. What causes it? Burning of fossil fuel, which emits carbon in the atmosphere. And perhaps for the first time, we (actually, those who care for mother Earth) began talking seriously about how to save the world.

How do we do that? Windmills. No, not by charging full steam a la Don Quixote at the mistaken giants, but building more of them. But they are very expensive, and definitely not cost-effective for developing countries.

The consensus, though, still seems to be "coal bad, windmills (and solar panels) good". Nothing wrong with it, except that today's world cannot satisfy its energy need (read greed) with just windmills, solar panels and bio-fuel (we'll come to that later).

This is where the Kyoto Protocol comes in. Though it came into effect in 1997, its process began five years before, at the UN Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. And though 150 countries signed it, GHG emissions kept increasing because emissions cuts were "voluntary".

In 1997, the signatories met in the Japanese city of Kyoto. A heated debate followed, and many an argument later they agreed on a protocol. All the signatories, except the US, have ratified the protocol since. Australia resisted ratifying it until new Prime Minister Kevin Rudd assumed office a couple of weeks ago. The Kyoto Protocol gave us the clean development mechanism, or CDM. That simply means a country can earn carbon credit by making certified emissions reduction, or CER, by cutting the use of energy, offsetting the damage caused to the environment by planting trees or through other eco-friendly means. And this CER can be sold to other countries.

What neither the protocol nor world leaders stress is that no matter which countries buy or sell CERs, it will result in more GHG emissions. This is a no-win situation for the environment, and thus human beings.

It's time we reconsidered the existing paradigm of development. The world has been talking about sustainable development. But as one of India's leading ecologists, Debal Deb, says: "It is common understanding among natural scientists that if development means unlimited growth in production and consumption of materials, sustainable development is an oxymoron. That's because unending growth of anything in the universe is impossible - except perhaps the universe itself."

The fact is development can be sustainable only in a zero growth economy, which would improve the quality of everyone's life by ensuring conservation and equitable distribution of natural resources.

That, however, is not possible in today's market-ruled world. It's impossible to stop further depletion of natural resources. And no one realizes that better than the big companies that have caused the greatest damage to the Earth. To cover their crimes, they have jumped on the sustainable growth bandwagon. They claim to be returning as much as possible of what they have snatched from nature to mother Earth through so-called sustained "green" efforts.

Oil prices have kept rising despite the increase in production of bio-fuel. And who has benefited? Multinational oil companies, of course, although the West keeps blaming China and India for the price hike.

Bio-fuel is clean energy, and many countries took to it in right earnest. But the use of corn and other food crops to make bio-fuel has caused a crisis: food prices throughout the world have shot up. This confrontation between food and fuel is tilting, very slowly though, towards the latter.

So what is to be done? We are standing at a crossroads. One path, as the old saying goes, is easy but can lead to doom. The other is tough, but can ensure a better future for our children. The easy path, as is self evident, is the one of unlimited economic growth. The tough road is one of controlling our greed. In short, if we want humankind to survive, we have to change the current model of development, the development that focuses more on money than the environment or welfare. And as long as money gets precedence over life, we will not be able to save anything, let alone the environment.

On the eve of India's independence, Mahatma Gandhi was asked whether the country would follow the British path of development. He replied: no one knows how many worlds would be needed if India were to follow the British development model. No one knew then, but the UNDP, which cited the episode in its latest report, says if the whole world were to follow the developed nations' development model, we would need nine planets the size of Earth to dispose of its carbon emissions.

There is similarity in what Gandhi said in 1947 and what Marx wrote almost a century before that in Capital, Volume I: "The more a country starts its development on the foundation of modern industry the more rapid is the process of destruction."

Marx's critique of capitalism, writes Deb, endorses the strong sustainability argument that industrial development is unsustainable because monetization of the natural world causes progressive degradation of human life and the destruction of nature.

In reply to Nobel Economics laureate Amartya Sen's Poverty and Famine, Deb writes: "Socialism envisages a sustainable, socially just society. Strong sustainability, endorsed in the eco (socialist) view contends that money cannot buy the right to deplete the natural world; (strong sustainability, as opposed to weak sustainability, forbids any further depletion of natural resources to ensure human beings, including future generations, are not deprived of the goods and services of nature, and) reiterates Marx's contention that: 'Even a whole society, a nation, or even all simultaneously existing societies taken together, are not the owners of the globe. They are only its possessors, its usufructuaries, and, like bona patres familias, they must hand it down to succeeding generations in an improved condition'."

The world can only ignore Marx (and Gandhi) at its own peril.

The author is a senior editor of China Daily

(China Daily 12/21/2007 page11)

|

|

|

|

|

|