Students subsidizing British universities

Updated: 2007-12-13 07:42

Picture this: a top 30 university in China is just completing its mid-term exam week in its "international program" for students preparing for degree courses in Britain.

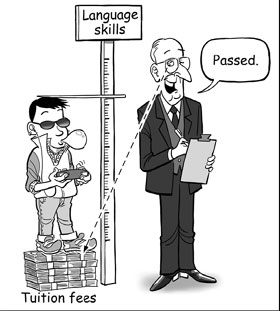

The results are not good. In the listening skills exam, for example, only four out of 54 students in two classes managed to pass. Is this a crisis? Are the students' dreams of education in Britain fading away? Perhaps that should be the case, but it is not.

These students may not be able to understand lectures; they may not be able to write a grammatical sentence or answer questions. But they can contribute something that keeps the door to Britain open: they can subsidize new British universities ranked outside the top 60 and thus keep fees for British students at a lower level.

Their financial contribution is significant. Thousands of students across China take these Sino-UK courses every year, run by dozens of Chinese schools and universities.

Most Russell group universities and many others in the top 50 protect themselves to a certain extent. They insist on a high score from the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) - a level 7 or 7.5 - as part of the admission criteria.

Demand for places at these universities, which have the best reputations, is such that they can afford to remain more discriminating. But, sadly, other universities are very willing to accept IELTS 6, thus welcoming students who may struggle to do well on courses.

The huge rise in China's middle class provides the context for this impact on the British education system.

At China's end, this is what happens: every summer, the country runs its national university entrance exam. Most high-school students who do well in the maths, Chinese, English and science tests taken by millions, will go to a respected domestic university. But not everyone can get into a well-regarded establishment such as Peking University or Tsinghua University.

So what is the best option for those children of the growing Chinese middle class who do not get in? Putting your offspring into those considered to be second-string Chinese universities would involve a loss of face. Better, then, to stump up the cash to ship them off abroad.

The top 30 Chinese universities might not let these students join the ranks of their normal intake, but they will accept the students' money and offer a place in a private school they run that has an international link with a British university.

Since the late 1990s, the numbers of Chinese students coming for undergraduate and postgraduate studies in Britain has ballooned. The problem early on in this trend was that 40 percent of Chinese students were failing their British exams. So followed the establishment of "international foundation programs", designed to act as a transition between the Chinese education system and Britain's.

In these programs, Chinese students are expected to learn to listen, work in teams, contribute their ideas in class discussions, analyze texts and write in paragraphs.

These programs, on the surface, are an excellent idea. The pre-masters course run by the Northern Consortium of British Universities has its strengths in training areas such as research methods and presentation skills.

However, as these programs have proliferated, the standards have not been maintained. In the mid-term exam on one program in China, a business teacher said that in one of his classes, 75 percent of students failed.

There is an unwillingness to grapple with the problem. This particular Chinese university initially stated that students who missed three classes before the mid-term exam would be excluded from the test; it did not happen.

The mid-term exam results will add a few grey hairs to the heads of frustrated foreign teachers on these international programs. However, there are many vested interests in making sure the system continues and that those who fail are rescued.

Chinese students who cannot listen, speak or write after around eight years of formal English lessons may well still find themselves on their way to Britain. Their inability to do well means more students for professional courses from June to September in British universities.

These charge thousands of pounds - a nice little top-up for British universities already charging 10,000 pounds to 15,000 pounds ($20,364 - $30,547) for tuition fees for the actual course.

British universities boast on their websites about links with Chinese counterparts. They rarely highlight the mismatch between expectations and results on both sides. Nor is there a focus on why those links exist. It is not to diversify student intake, in most cases. The links are, as one teacher ruefully says, about "cash flow".

It seems that, whether or not the international program is good, the teachers and program organizers face exactly the same issues: unmotivated students and pressures from British universities to increase the numbers taking up places.

Unsurprisingly, some students on some programs realize low-ranking British universities are desperate to have them, so they have even less reason to raise their game.

The more China prospers, the more students will come to British universities. Yet, in the current system, the British universities that keep their China links to a minimum will almost certainly be the ones that prioritize quality over cash cows.

The Guardian

(China Daily 12/13/2007 page11)

|

|

|

|

|

|