Mongka Khan The Rivertown

By Pauline D Loh (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-12-06 09:54

|

Large Medium Small |

|

|

Life-sized bronzes populate the magistrate's court, a replica which shows Southern Song justice at work. [Photos by Pauline D Loh / China Daily] |

|

|

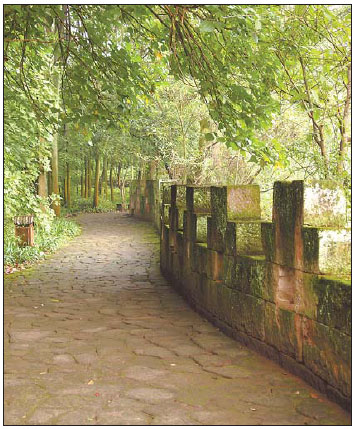

Quiet moss-coated paths are now silent and green. |

A little river town in China once changed the course of European history when it defeated a great Khan. Pauline D Loh tells the story.

Our little motorcade made its way noisily through the main street, police escort blaring its sirens to clear the way. We squirmed a little in our official black limousine, unused to such privileges and uneasy about the inconvenience we were causing the local folks, some of whom had stopped marketing to stare, curious about the commotion.

Thankfully, we were soon out of town and climbing up the mountain roads to Diaoyu Cheng, or Angling City, an historic site in Hechuan that is 45 minutes away from the municipality of Chongqing.

Many years ago, students from China's most famous military school, the Whampoa Academy, also took this road.

They, like us, came here for a lesson in strategic warfare, to learn how a little army of Southern Song soldiers held on to a river town outpost for 36 years against unrelenting attacks from the invading Mongol army.

It was here that Mongka Khan, one of Genghis' grandsons and his heir, stubbornly besieged the unassailable cliffs for more than three decades. He was wounded in a last battle in 1259, and some say he died in a fit of rage when the Song governor sent him a live fish - a message that Diaoyu Cheng had enough food and water and could hold out to the bitter end.

The town folks are very proud of the fact that this memorable battle averted a huge Mongolian invasion that would have changed the course of European and African history. After Mongka's death, the other khans leading the attack on the West turned back and hurried home, as the jockeying for the next in line to the Mongol empire began.

It was another decade before a concerted effort by the Mongolian army finally battered down the defenses and paved the way for the Yuan Dynasty, which ruled China for almost 100 years from 1271 to 1368.

These days, the only sounds at Diaoyu Cheng are the echoes of history, with intermittent bird calls disturbing the verdant quiet. Bamboo groves fringe the stone paths that lead through spring-fed reservoirs, retrofitted military barracks and moss-covered ancient city walls.

Cannon platforms dot the battlements, and our guide leads us first to the one at the east gate where the shell wounding the Khan was reputedly fired.

We stand on the edge, looking down sheer cliffs to the sloping banks far below, now carpeted with terraced rice fields and vegetable gardens. The riverine mist rises and veils the vista with a filmy layer that gives the whole scene an otherworldly dimension. Suddenly, we can almost hear the battle cries of the Mongols as they charge up the embankments.

Diaoyu Cheng, like most river habitats along the great Yangtze, has many Buddhist relics. Along one cliff, an ageless reclining Buddha rests, carved out of the rock, its face blurred by thoughtless attacks in an age where youth had lost its reason. No one knows exactly how old it is, although it had been here for as long as anyone can remember, before the Song and probably dating from the Tang dynasty.

It was thought-provoking to realize that these serene images of peace and universal goodwill should have witnessed the bloody battles between two armies.

We wandered back along vertigo-inducing steps to where the old city gate stands. It is still an imposing edifice with a steep stone path that dips frighteningly downwards. This flight of steps was added a lot later. During the heated battles those thousands of years ago, it had been all sheer walls.

To get up and down, the locals had chiseled out buttress holes in the cliff face to support wooden planks that could be removed in the event of an enemy attack, leaving no toeholds for the opposing army.

As we panted up the steps again, we saw a plaque left by the Whampoa Academy students 70 years ago, a sort of formalized graffiti that said: "We were here!"

It brought a smile to the spouse's face, and he reminded me we also had the venerable Jiangwu Academy in our home city of Kunming, another famous military campus.

Our next stop was Diaoyu Tai, the natural stone embankment where legend says a heavenly deity once saved the town from famine by casting his rod into the river.

He certainly had a great view of the waters, at a point which marked the confluence of three rivers - the Yangtze, the Jialing and a smaller tributary.

As my husband hurried down cliff to see more Buddhist relics, I decided to stay put and admire the sites of the old granary and the arsenal factory.

Deep groves had been carved out of the solid granite ground. We can still see the foundation on which the great stone mill rested, turned by donkey or horse power. A sort of minor irrigation system made sure that the milling ground could be washed easily after the work was done.

Farther along, the old arms factory stood separated from other human settlements on the hill.

Deep depressions marked the site, and I was told this was where gunpowder was produced. Now, recent rains had filled the cavities, and the little ponds reflected the skies above - an oddly tranquil image for a historical relic with such potential violence.

The juxtaposition of war and peace continues as the eye travels east from the armory and meets a temple, where the Song soldiers must have gone for spiritual solace and comfort.

On Diaoyu Cheng, efforts have been made to preserve Song Dynasty life as it was, including a well-thought-out representation of a magistrate's court of that era.

Life-sized bronze sculptures represent the officials and guards in the court, and a spirit screen guarding the entrance to the court is embossed with a mythical creature that closely resembled a kylin, the Chinese unicorn.

No, says our guide. It is not a unicorn.

It is a creature named tan, whose legendary greed was so great it not only swallowed everything made of gold within reach, but it was about to swallow the sun, which looked like a great ball of gold to it.

"Tan" means greed in Chinese, and the creature was embossed on the spirit screen so officials going in and out of the court were reminded constantly of the dangers of corruption.

At the end of our tour, I could not help but feel awed but also a mite maudlin.

History is so relentless. Diaoyu Cheng is now applying to get on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list. I hope it succeeds, if only because it has so bravely held on to its heritage all these years.