Rice noodles'Mr Big

Updated: 2018-07-27 07:17

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

The turnaround story of a rice noodle mill in Jiangxi province is one of innovative craftsmanship transforming the traditional staple against the background of the nation's reform and opening-up, reports Dara Wang.

Jiangxi Wufeng Food Co - once a small rice-noodle mill in Huichang, Jiangxi province - has achieved its legendary status in Hong Kong after nearly crashing and burning in the late 1980s. Today, about 150 bowls of its rice noodles are sold every minute at two of the biggest rice-noodle chain restaurants in Hong Kong - Tam Chai Yunnan Noodles and Tam Jai Sam Gor Mixian.

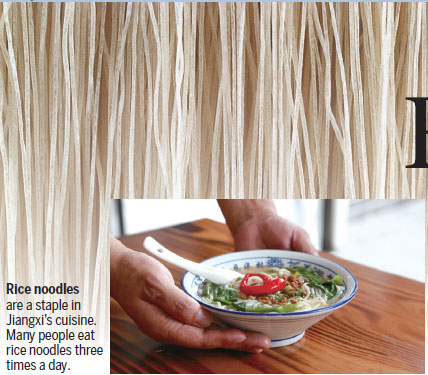

Aficionados credit the noodles' popularity to their distinctive chewy texture.

The company's success came only after three years of trial and error, strain and frustration, but it stands as an example of how small companies can succeed.

Three decades ago, rice noodles had quite a different texture. Neither were they popular. Before becoming a subsidiary of China Resources Ng Fung in 1996, Jiangxi Wufeng had been a 20-worker factory under the food bureau of Huichang county since the 1960s. Sales were slow. Production was less than 10 tons a year and never improved. By 1989, things were so bad that people got indigestion, gas pains and flatulence from their noodles. It was time to create something better or go broke.

Seven workers, including Guo Yonghong, a mother of a one-year-old girl at the time who later became the company's manager, formed a research and development team to take charge of machinery design, data handling, plant operations and quality control. "Our goal was to produce elastic rice noodles, suitable for everyone, even those with stomach problems," recalls Guo.

They found the problem in the fermentation process, which she calls an essential part of the rice noodle making process. Fermentation consumes the sugar in an oxygen-deprived environment, producing organic acids or gases that cause stomach acidity and upset.

Fermentation could only make the rice 50 percent cooked. The low cooked level made the noodles lose the chewiness so they were not very appetizing, explains Guo. Not only that, they were prone to breaking in boiling water.

The team overhauled production by abandoning the traditional fermentation process and made a new formula from scratch to avoid stomach upset caused by organic acids and gas through fermentation.

They soaked the rice, mashed it and pressed it into noodles at high temperatures. The first results were disappointing, says Guo. The unfermented rice was only 10 percent cooked after all that and the rice noodles still broke in boiling water.

It was found, after thousands of trial tests, that when the rice was crushed into fine particles, small enough to pass through a 0.25-mm sifter, it could reach a higher cooked level at 75 percent after pressing.

Then it was back to the drawing board to find a way to cook the noodles through and through. The noodles were placed in an enclosed room at a specific temperature and humidity, and kept there for eight hours. The noodles produced then were 85 percent cooked, and two minutes' steaming nearly completed the cooking at 95 percent.

Still, it wasn't perfect. "We got the ripe level we wanted, but when the rice noodles were taken out of the steaming room, we were all stunned," says Guo. The noodles had hardened and were glued together. They tried to force the noodles apart by hand. No luck. "Even if we had used all our strength until our hands turned red, we still could not separate the noodles."

They did everything, including covering the noodles with a cotton quilt soaked in water. They tried an induction cooker, hoping the steam would soften the noodles. Nothing worked.

Months later, team members' patience almost snapped; one of them vented his frustration by pitching a handful of the rice noodles into a vat of water. The rock-hard noodles came apart. Then, they stood up in the boiling water and did not break. The noodles held their shape even when a comb was run through them.

The factory adapted the combing method and has since used a comb-shaped stainless steel machine to separate the rice noodles.

The experiment took three years during which Guo worked from 7:30 am to 2 am the next day for 15 yuan ($4) a month. She had almost no time to eat and sleep and suffered stomach problems. Her weight dropped to 45 kilograms. Her dorm closed before midnight so she had to squeeze through the iron bars of the front door. She had to become something of a contortionist.

The day-to-day intensive work didn't beat Guo, who has never regretted joining the team even during their toughest times. When talking about her daughter, she softens her voice. "She's the one I owe most."

Guo hesitated for some 10 days out of concern for her little daughter when she was tasked to join the research and development process of rice noodles. She eventually took up the offer and had to send her daughter to her parents' home in nearby Ruijin county under a demanding work schedule. Guo's daughter did not live with her until she was in Grade 3 at primary school. This was Guo's greatest regret.

Efforts finally paid off. The factory became one of China's first chewy rice-noodle producers. All it needed was orders.

From overseas to domestic

In 1992, the factory took its new formula rice noodles to a food expo in Hainan province. They took a photo of a single rice noodle holding a 2,300-gram weight. A bundle of about 20 strings of rice noodles was enough to sustain the weight of a person weighing 48 kg. The photo attracted the attention of a Jiangxi-based company specializing in the import and export of cereals and oils. The company introduced the factory to China Resources in Hong Kong, which is now a Fortune Global 500 enterprise.

Two months later, the mill had its first order from Canada - 100 boxes of rice noodles, 2.4 tons. It took the factory nearly half a month to complete the order. They did not have a logo or packaging so they opted to use China Resources', and the company has stuck with that logo since.

The order came with a historical blessing, owing to the socialist market economy introduced the same year as part of the nation's reform and opening-up policy launched by then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping in 1978.

A series of economic reforms aimed at attracting foreign investment followed, resulting in China achieving average economic growth of 9.7 percent annually from 1978 to 2016.

The days of food shortages were still indelibly imprinted in the thoughts of people back then. Domestic purchasing power was limited. A 24-kg box of rice noodles produced by Guo's factory, priced at HK$180, was beyond the means of most people on the Chinese mainland back then.

The company steered clear of the mainland market for more than a decade until 2003, when it established its market overseas. As general living standards on the mainland improved, prices were no longer a deterrent.

Today, the mainland market takes up the largest share of Jiangxi Wufeng's sales volume. Last year, the company produced 30,000 tons of rice noodles, of which 55 percent was sold on the mainland (mainly in key metropolitan areas like Beijing and Shanghai), while the rest was sold overseas.

To stay competitive, Jiangxi Wufeng started an online store on Tmall.com - China's largest business-to-consumer online retail platform run by Alibaba Group - in 2014. But, about four years later, sales remained sluggish due to the low recognition of the rice noodles from Jiangxi, says Guo.

"To perform better in the mainland retail market, we need more branding awareness and recognition," she argues.

Many rice-noodle producers in Jiangxi have the same problem - the province does not have an established reputation for high-quality rice noodles amid stiff competition from Yunnan province and Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, whose reputations are well established.

Speak for Jiangxi

According to the Jiangxi rice noodle association, comprising nearly 100 rice-noodle producers, Jiangxi exported 30,000 tons of its signature straight-cut rice noodles last year. This accounts for over 60 percent of the volume of the nation's straight-cut rice noodle exports, ranking first among all provinces or regions. However, few in China know that those rice noodles are from Jiangxi, said Yang Xiaolin, secretary of the association.

To promote brand awareness, the association applied for a collective trademark which was approved in March this year. It will establish a set of standards, covering production exceeding national standards, annual sales volume and brand reputation. Members of the association adhering to the standards will be allowed to use the group's trademark.

Yang hopes the trademark will strengthen trust among consumers. "We would like consumers to know that rice noodles with this collective trademark are safe and reliable," he said. "Those of poor quality will be gradually weeded out."

Guo is currently investing over 2 million yuan to study fully automated production, and expects Jiangxi Wufeng's annual production capacity to reach 70,000 tons by 2020.

It's beyond her imagination that after three decades, the company could reach its level of success today, or that she would one day be developing innovative plans for the rice-noodle business.

The company, which now employs 856 people earning 3,500 yuan monthly, is increasing its production scale and developing its e-commerce to provide some 400 new jobs over the next two years.

"I hope that, one day, Jiangxi's rice noodles will be easy to get and become famous, just like instant noodles," says Guo.

In the near future, she hopes the first thing that comes to mind when people mention Jiangxi will no longer be poverty, but famous chewy rice noodles.

Contact the writer at dara@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 07/27/2018 page8)