A letter from Heaven

Updated: 2015-05-20 07:50

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Children's Cancer Foundation is doing its bit to ease the suffering of terminally ill children. And that includes taking them on a foreign trip in a wheelchair, if necessary. Ming Yeung reports.

Every Mother's Day has been a torture to Mrs Ng. Her daughter, Tracy, died in October 2008. She had cancer.

All that belonged to Tracy is put away in drawers and Ng and her husband never speak of her. It's as if the daughter they lost never existed, except for the pain that never goes away.

"We also live a lie. Some of our friends believe my daughter has been abroad, studying," Ng said. "When they asked why she hasn't come back, I tell them, 'she didn't like it here.' This is life. We all put on masks."

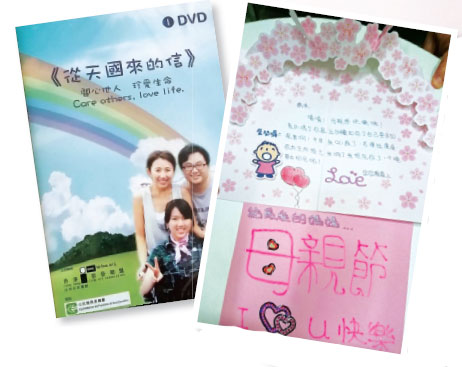

Three nights before Mother's Day (May 10), Ng took out the memorial book. Tracy had spent her final days writing her "letter from Heaven", to her mother and father and to her classmates. Tracy had sat on the very sofa where Ng now sat turning the pages, interleaved with keepsakes and family photos. There was Tracy, dressed as a princess, and here were the messages she had written from her heart, to those she loved.

"I'm sorry mama," wrote the 13-year-old. "I'm sorry for all the troubles I have caused. I wish I could repay you in the future but I won't have the chance. I'm happy that at the end of my life I did something to make you and papa proud. You two said I did great but I think you are better, because I'm your daughter. Without your guidance, how would I be open-minded? Without you how would I be this good?"

Ng could not stop crying as she revisited the bittersweet memories of her little girl. She said her head still hurt from her tears. She recalled, "Tracy was so independent and mature, unlike other innocent girls."

Live until you die

Maybe Tracy grew up so quickly as she had to cope with a deadly affliction since she was only 5 months old. A polyp was found on her vocal chords. It was removed through surgery but more kept appearing. In her short, tragic life, Tracy had 110 operations.

The hopelessness of her situation weighed especially heavily on Tracy who, being so young, couldn't figure why the illness kept dogging her. "A day lived is a day gained," Ng would tell Tracy.

"It's not about how long you live. It's about how well you live," Ng remembers telling her daughter.

It was July 2008. Tracy had just completed Form One in a Band One girls' school. Her doctor told her she had lung cancer and her time was short.

A month before the end, she was referred to the Children's Cancer Foundation (CCF), an NGO that provides palliative and home care for young people under 18 with cancer and other life-threatening illnesses and for their families. One of the missions of the foundation is to fulfill the last wishes of dying children, as much as possible, says Molin Lin Kwok-yin, CCF's professional services manager.

Lin has been in children's palliative care for 15 years. She says the goal of the foundation is to improve the quality of life for dying children through organized activities.

About 40 to 50 children die of cancer every year in Hong Kong. Over the past decade, there have been 180 to 200 new cases a year.

Even in the face of those numbers, there is no "terminal" ward for children and adolescents in Hong Kong's public healthcare system. There is no specialist training for dealing with dying children for doctors or nurses

A study by CCF and the Department of Social Work at the Chinese University of Hong Kong laid bare the inadequacy of the healthcare system for dealing with the most heartrending of all terminal cases - the children. The survey was taken among 680 pediatric professionals, between December 2013 and August 2014.

More than half - 60 percent of the respondents said they had only limited knowledge of palliative care. More than 70 percent said they had no idea of how to tell parents their child was going to die. They were under tremendous stress knowing they were not fulfilling their professional obligations.

Participants with working experience of 5 years or less experienced a significantly higher level of difficulties, the study indicated.

Wallace Chan Chi-ho, who ran the survey, said palliative care is more concerned with the holistic needs of child patients in dealing with issues related to death. It is therefore to be hoped the authorities would provide more training in palliative care to less experienced doctors and nurses. Chan said he also hoped the government would provide more support on policy and services.

"We encourage patients and their families to reach us earlier so that we can do more to help them. Accepting palliative care does not mean giving up," Molin Lin said, adding that CCF provides services from reducing distressing symptoms for patients to psychological support to their caregivers.

Last wish fulfilled

What do dying kids wish for? Well, much the same as healthy kids do. They want to go on outings, to amusement parks, for instance. The difference with sick kids is they need doctor's approval, plus special facilities, such as wheelchairs in certain cases.

Experiencing their dreams eases the pain suffered by dying children and lifts the hearts of their loved ones who will remember the special moments as long as they live.

Angel loved to sing. Before she died, she wanted to perform at her own live concert. CCF helped to fulfill her last wish, in 2011 when her condition was relatively stable. Her idol, Joey Yung, came as her special guest and so did an audience of hundreds who were swept up in her talents. Angel had a few years left in which to savor her fond memories. She died a few months ago.

Granting a child's last wish may become a race against time. "If a kid wants to do something, we have to do it as soon as possible, within our resources. If we waited for signs of improvement, it might never happen. We have to race against their failing health," Lin told China Daily.

CCF has funded annual overseas trips for some patients from underprivileged backgrounds and their families. A doctor, nurse and a social worker accompany them.

Lin recalls a teenage boy with advanced liver cancer who wanted to go to Japan. The foundation staff was worried. They were worried the ailing boy might die on the way. A doctor was called in and gave his approval for the boy to go. The boy had a wonderful time on his journey of a lifetime and died peacefully, two days after coming home.

"We can see on these trips that the kids and their families are so happy, forgetting for a short time the heartbreak caused by the sickness," Lin said.

Some last wishes of children are hard to be fulfilled. Lin has dealt with about 500 dying children. About 10 of them said their last wish was to die at home.

"Dying at home is not an easy choice. Parents of patients suffering from acute pain might worry that they can't handle it. It takes a lot of work to make this happen," Lin said.

Lin's first case was an orphaned child who lived with his older brother. What ensued proved a nightmare for the family. The child died before the medics arrived. The medical professionals were obliged to call the police who arrived to question the grieving brother to establish with certainty that the child's death was from natural causes. Then the press showed up to probe the matter.

Lin remembers the older brother of the child saying he was outraged. The police, he said, almost made it sound as if he had killed his brother.

"The whole process was very time-consuming and was a torture for the family. We have to prepare the parents who wish to have their child die at home and tell them the possible consequences," Lin reckoned.

Postscript

On Mother's Day this year, Mrs Ng received a final gift from the daughter she continues to mourn these many years later. In addition to "the letter sent from heaven" together with the memorial book to her mother in October 2008 after she died, Tracy left another gift, a card which she had given to Lin for safekeeping until it was time for Ng to receive it. Tracy would have turned 20 this year.

With trembling hands, Ng took the card Lin held out to her. The grieving mother could not hold back her tears though for all the sadness and the memories it stirred, but she thought it the best Mother's Day gift she'd ever received.

Tracy had been her treasure and when she died Ng's world caved in. "Everything I did was for my daughter. Now she was gone, I felt like there was no hope," she recalls.

Ng had lost about 50 pounds after her daughter's death. She felt moments of rage, for which there was no evident exploration and oftentimes she sank into depression. Time heals all wounds they say. For Ng the wound will never heal but she feels better.

Ng has learned to make it through remembering the words of her dear child now lost. "Life is good. Health is even better. Eat good. Live well."

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

|

Tracy, who would have turned 20 this year, left a card to her mother. |

(HK Edition 05/20/2015 page9)