A peek into the sausage factory

Updated: 2015-01-08 05:58

By Sylvia Chang(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

While the rose-sweet aroma of hand-crafted Cantonese sausages still figure in a typical New Year's Day lunch in HK, the craft of making this generic food item may not last forever. Sylvia Chang reports.

It was six o'clock on a winter morning. The temperature fell to 9 C, much colder than usual in this tropical city. In the dark, chilly winds blew in gusts. Only a few people were walking the streets of West Point. On the 13th floor of an industrial building, located at Connaught Road West, seven workers, in short-sleeved T-shirts and aprons, had already labored for an hour. They were making a traditional local food item, known for its rose-sweet smell - Cantonese-style sausages.

With a recorded history of more than 600 years, Cantonese-style sausages are a favorite in South China. People especially like to eat sausages on the last day of the year. It's a food item they bond over. What many people enjoying sausages don't care to notice is that the art of making the product is on its way out.

Yu Kam-wah, 59, owner of the aforementioned factory, has spent most of his life in the trade. He began learning sausage-making at eight. The oldest son in the family, Yu inherited the factory from his father, who had fled to Hong Kong from the civil war on the mainland in the 1940s. The sausage industry boomed after mainlanders immigrated to Hong Kong in huge numbers in the 1950s. It was a good time to set up a small family-owned business, as Yu's father did.

"Back then we made sausages at home, or on the rooftop of a building. Everything was done by hand. The family started working at dawn and I would join them after school," Yu recalled.

In the 1980s, the trend of sourcing processed food from the mainland began, leading to the inevitable decline of the sausage industry. And with mass production replacing handcrafted sausages, there are less people to appreciate the craftsmanship. A decade ago, there were 10 sausage-making factories in the same industrial building but now only two are left, says Yu.

Not worth the trouble

"This is a dirty and arduous work. Young people wouldn't like to do it," said Yu Kam-choi, 55, binding sausages with hempen cords and hanging them onto a big iron hook. He's the fourth child of the family and also the youngest among the workers.

"It looks easy, but requires a lot of effort," Yu Kam-choi continued, demonstrating the craft of tying cords to give the material the right shape.

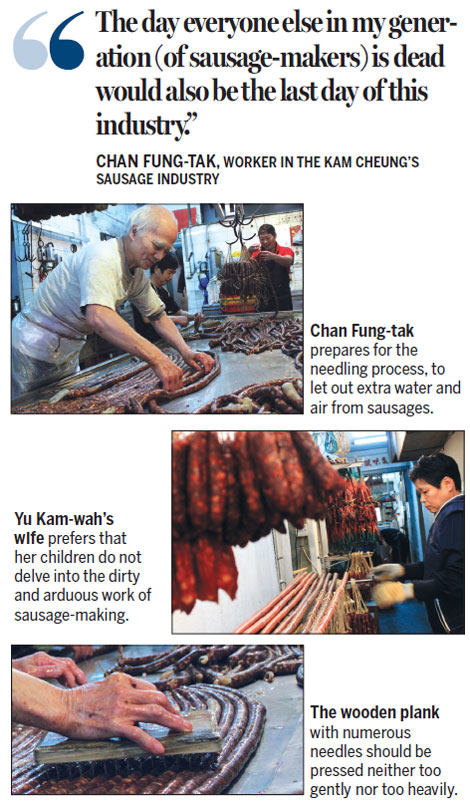

Beside him stands Chan Fung-tak, who began making sausages in 1957. With the abundance of grey in his hair and eyebrows, he is turning 80. He lifts a wooden plank with numerous needles sticking to it and presses it against the sausages, to squeeze out extra water and air. It's a traditional tool in which the needles, as Chan points out, are neither too light to get impaled on sausage peels nor so heavy that the meat would get pushed out of the skin.

Chan joked that he would like to paste the photos that we took to illustrate this article on his coffin, as a token of the passing away of a craftsman of a dying art. "The day everyone else in my generation (of sausage-makers) is dead would also be the last day of this industry," Chan said.

After needling was over, workers tied the long sausages tightly, suspending them from a three-meter-long bamboo pole, before putting them on electric stoves to dry.

The last step is to cut out the small strips and pack dried sausages in dedicated bags. Yu Kam-wah's wife, surnamed Lee, performs the task. She has been doing it ever since she got married to Yu. Apart from the time spent in raising children, she has worked alongside her husband all these years.

"But I never encourage my children to do this. This industry is dying." Lee laughed.

Usually Hong Kong people prefer eating sausages with rice. They put dried sausages in rice, combined with chicken and seasonings, such as fermented soya beans, and then steam all the ingredients together. Boiling water releases the sweet smell of sausage in the air, spreading vibes of happiness in the family.

Orders for sausages increase in the lead-up to the New Year. Once that passes, Yu and his workers go back to their hometowns to do something else. "Sausage industry is a half-year business. Nobody would like to eat this greasy food on a hot day," said Yu Kam-wah.

He is rather taciturn in his responses, when asked about the difficulties he had experienced all these years. All he would say was, "It's hardjust hard"

"All those difficulties were endured by him alone," said his wife, cutting the ropes binding the sausages. "During the earliest years, he tried again and again to make the most delicious of sausages. He just couldn't figure out a way to make it work. "

Yu Kam-wah's pursuit of perfection led him to sink deep into melancholia. Now he has to take medicines to cope with depression. He had worried himself sick trying to nail the art of making the perfect sausage. He believed this was what his life was about.

But the worst is probably over. "It's much better nowmuch better" Yu murmured.

Contact the writer at sylvia@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 01/08/2015 page7)