More than the job's worth

Updated: 2014-03-14 07:25

By Li Yao(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

A mainland immigrant seeks job-hunting advice from the New Arrival Women League. |

|

Mainland immigrants protest lack of government support to boost their job opportunities and demand recognition of their qualifications and professional credentials gained on the mainland. |

In a city hungry for talents and facing a declining work force, prospects for recruiting outside talent are sharply curtailed by layers of red tape and bureaucracy which force many mainland professionals out of their chosen fields and into menial jobs. Li Yao reports.

Shi Yijin, 42, didn't know how to answer her former colleagues, nurses from the mainland, when they lamented the heavy price she paid for moving to Hong Kong. Nobody was trying to be mean but Shi was unable to conceal her overwhelming sense of defeat.

Her husband is a permanent resident here, so in 2008 she came with her eight-year-old daughter so the girl could get a Hong Kong education. Shi's colleagues at Fangchenggang municipal hospital in Guangxi province warned what would happen but she came with high hopes that her 18 years' experience as a senior nurse and her commitment and passion for her work would assure continued progress on her career path.

A receptionist at the Nursing Council of Hong Kong gave her a bunch of forms to fill out to apply to write the nursing qualification exam. She had to supply documents including her diploma and transcripts from the nursing school she attended, and detailed records from the hospitals where she had interned and practiced.

Document fault

The Nursing Council found fault with her documents repeatedly. Her application dragged on for years. Beijing's health ministry considered her nurse's certificate nullified once she quit her job on the mainland and moved to Hong Kong. Ministry officials wouldn't even write her a confirmation letter and, without that, the Hong Kong Nursing Council wouldn't even look at her application.

"What I asked is merely a chance to take the exam, not a job at a hospital immediately," she said with a note of reproach toward the unhelpful bureaucrats. She was blocked at the doorway, despite her years of experience. Under the circumstances, she doubts anybody would listen to her plea that the government allocate resources to help professionals like herself make the cross-border transition.

Refusal by Hong Kong institutions to recognize academic and professional credentials from the mainland has made Hong Kong a good deal less attractive to many mainland professionals, says Chou Kee-lee, a professor at the Hong Kong Institute of Education examining immigration policy and poverty.

About 30 percent of working-age mainland immigrants are overqualified for their positions in Hong Kong, says Chou, and at the same time, they have been held back from pursuing the fields in which they were trained.

The percentage of mainlanders with post-secondary education in Hong Kong doubled from 7.9 percent in 2006 to 16 percent in 2011, based on the 2011 census. There's little improvement in their standing in the job market, though. Many mainlanders with tertiary education, including academic degrees, work well below their qualifications. Some are compelled into blue-collar occupations where job stability can be uncertain, the hours long and the pay poor, Chou said.

Chou has reminded the Hong Kong government that highly-trained mainland professionals, like anesthesiologists and cardiology nurses, can become contributors to mitigate Hong Kong's shortage of medical staff and - with the aging population and low fertility rate - its shrinking workforce.

Hong Kong authorities, he contends, should facilitate the cross-border movement of people with professional qualifications - even if that should entail providing intensive training courses to allow them to acquire whatever qualifications they may be lacking. The sooner the better, Chou adds. He believes that a little extra training to bridge the gap between mainland and Hong Kong in specific professions would mean a whole lot of difference to Hong Kong's much discussed search for professional talent.

The difference between breaking or making someone

For someone like Shi, the former nurse from the mainland, the more accommodating approach proposed by Chou would open the door for her to provide badly needed services to the community. It would also be a boon to her psychological wellbeing.

Shi thought she had a shot at making her own way to pass the qualification exam, without having to spend a fortune and three solid years at a nursing school in Hong Kong.

She bought textbooks. She paid particular attention to the study of English, thinking that would be the most challenging subject for her to master. She had no outside support to provide her with guidance. She was completely on her own. All the while that her applications to write the qualifying exam were rejected, she went to the Employees Retraining Board and earned a certificate as an instructor of Mandarin. That career lasted a year - but then students gravitated to teachers who came from the north of China, who speak standard Mandarin. Her best working days in Hong Kong were over. "It was exhausting, to be sure. Each one-on-one session took only an hour. I spent more time commuting from one student's place to the next. But at least there was some respect when they talked to me," Shi recalled.

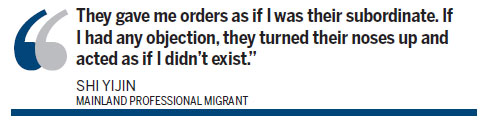

That sense of having value and of being treated with respect, quickly evaporated at her next job, as a part-time domestic assistant and company cleaner. Her co-workers were two semi-illiterate women in their 60s. "They gave me orders as if I was their subordinate. If I had any objection, they turned their noses up and acted as if I didn't exist," she said.

The difficulties have started taking a toll on her health. Her cervical pillar hyperplasia, a degenerative condition has worsened. She was diagnosed with depression in 2010 and has kept up regular hospital visits every month. She has been getting a monthly disability allowance for two years.

"Isn't it ironic that I hoped so strongly to continue my career to look after patients, but now that hope is in tatters? I need to be taken care of myself" Shi said sadly. With her self-confidence nearly destroyed, she doubts that she would be able to perform competently as a nurse today, even if she were offered a posting.

The end of her career hopes have not silenced her however. She knows more than 10 mainland nurses, all women, facing struggles similar to her own. Shi has encouraged them to take up the battle on behalf of other mainland women who want to come here. "Think of doing this for young nurses who may find themselves trapped in the same way," she urges the other nurses.

Despite her debilities, few could match her persistence in petitioning government agencies demanding that they acknowledge the problem and offer more support to newcomers. She can't claim real progress at this stage. She believes if she can raise a chorus among the disenfranchised that her efforts will have been a success. So far they've all given up. They take up their work as housewives, cleaners, and health-care assistants at private households or private elderly homes.

Chen Yan-xia, 40, a nurse with 13 years' experience at a hospital in Enping, Guangdong, wishes someone had been campaigning on her behalf when she came to Hong Kong in 2006 for a family reunion with her husband in Hong Kong. She was unconcerned that her nursing certification was going to expire the following year. By the time she realized that the need to file her application to write the nurse qualifying exam was urgent, her certification had expired and she was too late. Now, she works part-time as a healthcare assistant helping patients in private households, earning less than HK$500 on a 12-hour shift a day.

Chen believes an effective orientation program would have set her on the right course.

"Being a nurse is a decent job on the mainland, a respectable one. In Hong Kong, I found myself suddenly plunging to the bottom of society and losing contact with middle class people. I feel diminished when running into ex-colleagues and facing the dreadful comparisons," she admitted.

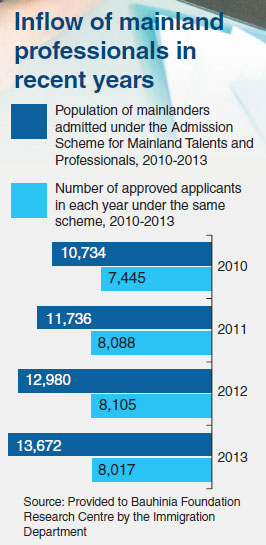

Teachers, accountants, and even artists are also swept up in the chaos stemming from the steadfast refusal among Hong Kong institutions to recognize qualifications from the mainland. There appear to be no exceptions even among those accepted for entry into Hong Kong under the Admission Scheme for Mainland Talents and Professionals.

Contact the writer at liyao@chinadaily.com.cn

(HK Edition 03/14/2014 page1)