No comfort for 'comfort women'

Updated: 2014-03-07 08:28

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Saturday, March 8 is International Women's Day, a day when in this part of the world, many pause to remember the 200,000 women throughout Asia who were forced into sexual slavery during the Japanese War of Aggression. To this day, Japan still has made no apology to the victims. Ming Yeung reports.

On Ship Street in Wan Chai sits an old two-story red brick building, said to be one of the most haunted places in the city. Perching atop a flight of granite stairs, Nam Koo Terrace is believed to have been a place where young women were forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese Army. So local legend holds. The building has been long since abandoned and now sits derelict. Any record of what may have happened here during the four-year Japanese Occupation from 1941 to 1945 is long lost.

With the approach of International Women's Day every year, the cry for justice is raised again on behalf of more than 200,000 women forced to become sexual slaves to the Japanese Army in Korea, on the Chinese Mainland, in Taiwan, Hong Kong and the Philippines. Many of the victims have spoken out demanding compensation and an apology from the Japanese government.

The recent resurgence of Japanese nationalism has fueled anger among the victims, now in their 80s and 90s, and rapidly running out of time.

Victims' testimony

Wan Aihua was the first of the victims on the Chinese mainland to attest to the Japanese atrocities against women. She spoke out in 1992. Abducted for the first time at the age of 14 and forced into sexual slavery three times, she suffered multiple fractures and ultimately was left infertile by her Japanese captors. Encouraged by her example, other survivors came forward across the lands formerly occupied by Japan. These victims added their accounts to the history of Japan's War of Aggression and joined Wan in demanding an apology from the Japanese government.

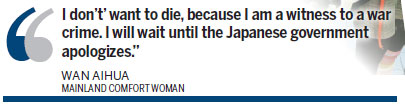

"I don't' want to die, because I am a witness to a war crime," said Wan. "I will wait until the Japanese government apologizes," she vowed.

The apology has never come. Wan died on September 4, 2013 at the age of 84, in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, her hopes unfulfilled.

"We do not know how many women suffered in this way (in Hong Kong), nor how many, if any, are still alive," stated a document presented by the Hong Kong Government to the Legislative Council in 1993. "None has approached us for assistance, nor otherwise become known to us," the document continued.

Women who became victims of the Japanese Army in other countries have come forward, but not one single woman from Hong Kong has spoken out to say she was forced into sexual slavery. It was reported that during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, about 10,000 women were forcibly "recruited". The colonial government appears, however, to have been unaware or indifferent.

Professor Adam Lui Yuen-chung, president of the Hong Kong History Society and former head of History Department at the University of Hong Kong, said without documentation, without the testimony of victims, it is impossible actually to prove women in Hong Kong were forced into prostitution.

In its 1993 assessment, the Hong Kong government noted the dim prospects for compensation to the victims, in any case. "If any such cases did become known to us, the Hong Kong government would consider sympathetically how we could assist them. But the scope for legal redress (from the Japanese), is constrained by the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951."

Legal bases removed

The San Francisco Treaty of 1951 and reparations made under terms of the treaty by the Japanese government, fully discharged Japan's obligations for the damage and suffering. The treaty removed all legal bases for further claims.

Japanese writer Wani Yukio, however, states plainly in his book Silent Years that after extensive research, he concludes that atrocities did take place. "Hong Kong indeed had 'comfort stations', as well as 'comfort women', yet unlike other areas, none of these victimized 'comfort women' came forward publicly to fight for compensation," writes Yukio, the grandson of a Japanese colonel who was stationed in Guangdong during the war.

In the book, Yukio cites Wan Chai, Shek Tong Tsui, Tsim Sha Tsui and Sham Shui Po as the four main areas where the Japanese set up "comfort zones" in Hong Kong.

There was a comfort zone serving Japanese in Wan Chai, an area where congregated many Japanese, and meanwhile, a comfort zone serving Chinese in Western District. The military confiscated more than 160 buildings stretching from Arsenal Street to Fleming Road in Wan Chai. The area was confined by wires and the army ordered the residents to move out in three days, making tens of thousands of people homeless, Yukio writes.

The book cites an account of one witnesses to the atrocities, Doctor Li Shu-fan, head of the Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital. Dr Li described finding an ambulance stolen from the hospital outside what was represented to be a "guesthouse" in Wan Chai. Closer inspection by Li, however, revealed the place was indeed a comfort station, housing "about 200 comfort women".

Japanese general officers later defended comfort stations calling them necessary to prevent the mass rape of civilian women by soldiers, and the attendant risk of spreading venereal disease throughout the army.

Fear of being viewed as debased, degraded by their society may be the reason why Hong Kong women have remained silent, theorizes history professor Siu Kwok-kin of Chu Hai College.

Siu noted that the women who provided sexual services to the Japanese fell into three categories. Some were local prostitutes, recruited by the Japanese. Others were prostitutes sent from Japan. Local women forced into sexual slavery comprised the third group.

Siu pointed out that during the late stages of the Japanese occupation, famine spread throughout the colony. Food supplies from Japan were being diverted to Japanese soldiers fighting in other parts of Asia. Half a million civilians from Hong Kong were sent across the border into mainland China. Many of the comfort women may have been among them, he added.

Also at issue for Siu is the teaching of History under the colonial government. The British intentionally concealed the passage of Hong Kong's darkest days from the Opium Wars to the Second World War, he argued. Blank pages were left in the local history so that people never knew.

The colonial government, he contended, wanted to set aside ethnic conflicts and strive for social harmony to push forward the development of industries and financial houses. During the 60s and 70s, major Japanese corporations became big players, heavily investing in the development of Hong Kong.

"Hong Kong people sort of anesthetized their sufferings against the backdrop of complicated Sino-Japanese and Anglo-Japanese relationships," Siu said, but he stressed that it's about time the current administration revived the lost history, to make Hong Kong's school children aware of that darkest period under Japanese occupation that lasted three years and eight months.

Though the victims in Hong Kong never were documented, they are not forgotten. Mei Li, founder of Hong Kong History Watch, is organizing an exhibition March 8, Women's Day - with photos borrowed from the Hong Kong Museum of History in Wan Chai. She says the exhibition documents the scale of Japanese brutality and the blight they have left on human history.

The wounds of the former comfort women will not even begin to heal without a proper apology from the Japanese government, said Mei Li.

"The Japanese denial of the history of the comfort women is akin to raping them again," charged Li, an expert in women's history and the slave trade.

Li has seen countless women suffer from immense depression and nightmares after being raped during her career as a medical translator in the US. She said the suffering of comfort women, raped on average 20-30 times a day, day after day, must have been far greater than the pain suffered from a single assault.

"Could you imagine having a life being raped by men one by one 20 times a day for several years?" Li asked. "Could you understand their pain?"

"To speed up their healing process is to acknowledge this issue and help spread the message," she continued.

Li has never encountered any of the sexual slaves of the Japanese aggressors for as long as she has researched the issue. She is confident, however, that any victims still out there will feel comforted that the campaign for justice is going on.

"We want to tell them even though we are complete strangers, we care about them and, moreover, the lesson and sacrifice of comfort women serves as a reminder of the devastation brought by wars, and we all need to keep that in mind," Li said.

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

|

Human rights activists protesting in Taipei in a campaign for Japan's apology and compensation to Taiwanese comfort women. |

(HK Edition 03/07/2014 page1)