Drawing the line on poverty

Updated: 2013-10-18 07:17

By Andrea Deng(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

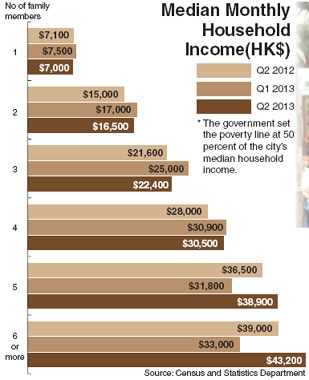

Late last month, Hong Kong took an important step in its war on poverty. Many experts believe the declaration of an official poverty line at 50 percent of the city's median household income is the most important step so far. Andrea Deng writes.

Chief Secretary for Administration Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor gave an impassioned speech ahead of the government announcement of the city's first official poverty line. "I share the viewpoint of the Chief Executive, that in a city like Hong Kong, such an affluent city, we really need to do more for the disadvantaged, for the low-income working poor," she said.

"Because I was the director of social welfare for over three years, I have first-hand experience of how appropriate government intervention can give our people better prospects. We can help people who want to help themselves, particularly children. We can give them hope. This is very close to my heart."

Law Chi-kwong, associate professor of social work at the University of Hong Kong and a member of the Commission on Poverty, said the declaration of a poverty line shows the government "acknowledges the problem and is facing it squarely".

"The poverty line gives us a quantified benchmark that makes it easier to compare the before and after effects of government welfare programs. It gives us a way to evaluate how effective they are," said Law.

It had taken endless machinations and debate to get this far. The first Commission on Poverty was set up by the Donald Tsang administration in 2005. It lobbied for a poverty line, said Mariana Chan Wai-yung, chief officer for policy research and advocacy, for the Hong Kong Council of Social Service (HKCSS). The plan was shelved to be taken out periodically to be kicked around like a football, then put away again.

"The government insisted Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) was enough. We didn't agree. The CSSA was not up to date with changing needs. But there was no basis for comparison (between the previous and current performance of the welfare systems)," said Chan.

"Now, the government will have to hand in transcripts," Chan concluded.

Families of the working poor

Lam has stressed often that with the poverty line in place, the administration's principal focus will be on policies to help working poor families, especially children. According to government figures, there are 300,300 non-CSSA households currently below the poverty line. Some are not eligible for CSSA, some didn't apply, perhaps out of pride. Among those 300,000-odd households, 48 percent, roughly 143,500 households, somebody has a job. There are 493,000 people in households that fit into this category: the working poor. Typically, they are not poor enough to apply for CSSA and not earning enough to afford decent living standards.

A report by Oxfam Hong Kong in April this year said that the Minimum Wage Ordinance, since it took effect in May, 2011, has not significantly reduced the number of working poor families.

"In the fourth quarter of 2012, 170,000 working households were living in poverty, only 800 households fewer than in 2010," the report said.

The report also found that about 70 percent of the city's children who live in poverty are children of working poor households.

Chan, of the HKCSS, noted that these working poor households have more children, stretching the family income to the point where it's simply not enough. The organization found that in these families, every 1,000 adults aged between 15 and 64 are required to raise 275 children under 15 years old. In comparison, the ratio for the overall Hong Kong households is 1000 to 160, Chan said.

Most of the working poor families earn between 40 percent and 50 percent of the median household income. "If these families were given a subsidy, we might be able to lift them out of poverty," Chan said.

Sole breadwinner

Ho's family is an example. Ho is an assistant chef. He works 12 hours a day, seven days a week and is the only breadwinner of his family. When the Minimum Wage Ordinance took effect in 2011, Ho's monthly salary rose from HK$9,000 to roughly HK$10,000. A year later, he got another raise. Now he gets HK$11,000.

He's applied for the Work Incentive Transport Subsidy, which gives him HK$600 a month to offset the cost of riding public transit to and from work.

His family is hovering just above the poverty line for a family of three. Things haven't changed that much for the family since the implementation of the minimum wage. Two years ago, the Ho's were living in a windowless, 70-square-foot subdivided unit in Sham Shui Po. Their daughter, four years old at the time, was diagnosed with allergies, affecting her nose and sinuses.

Ho and his wife concluded the little girl's problems probably stemmed from lack of ventilation. They moved to another subdivided flat in the same district. This one had a window. The window and the sunlight added another HK$1,000 to the rent.

The place is so cramped, there's not even enough space for a fridge or washing machine. It costs HK$3500 for all that. Mrs Ho washes clothes in the plastic tub which she used to shower her daughter a few years ago. She has to shop for food every day. With no refrigerator the food would go bad if not used right away.

"It doesn't take much time to clean the house. Basically I just need to clean a few tiles on the floor," said Mrs Ho. They sleep in bunks - Ho in the upper bunk, his wife and daughter in the lower.

The family has applied for public housing estate and been waiting for five years now.

Ho doesn't get much time with his daughter. He's at work seven days a week. She goes to school before he gets up. She's asleep by the time he gets home from work.

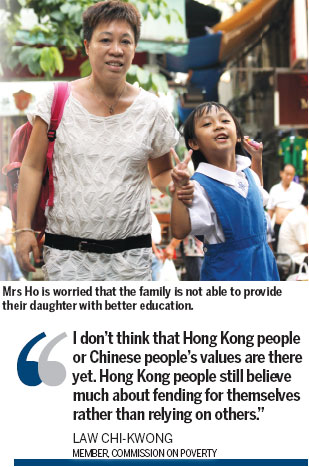

Besides paying for their daughter's allergy medication, the Ho's are paying tuition for the girl to take English classes after school.

"My daughter only attended the half-day kindergarten before because the government subsidy was only enough to cover that much. So now she has to catch up on a few subjects. I could still help with her Chinese and general knowledge. But neither me nor my husband speaks any English," said Mrs Ho.

"She's only in the first grade now. School will get harder and harder. I'm worried about not being able to get her a good education," she said.

Expectation of change

Several organizations, including Oxfam Hong Kong and the HKCSS, have advanced proposals for low income subsidies - for the working poor. Law remarked, however, that the government would have to assess the impact on the labor market before going ahead with a subsidy program.

"For example, we have to consider that if the family receives additional subsidies, some family members might quit their part-time jobs, so the family income will stay the same. This is the actual experience in other countries. I think we need to be cautious in pushing subsidies," said Law.

He said that it would be better to improve the current existing welfare schemes rather than introducing substantial changes, so that the labor market would not suffer any sudden, jarring impact.

Besides cash transfer, which are the simplest and most transparent measure, there are other forms of measures which could encourage more people to work and achieve self-reliance. Child care services to the help working poor households would be a big step. Day care services would free up many people to go back into the labor market, Law said.

Many have also voiced the hope of improving the scheme, saying CSSA should not give the boot to young people as soon as they finish tertiary education. Young graduates cannot be counted as part of the family unit under CSSA, based on the principle that graduates should be able to fend for themselves.

The reality is, Law argued, it is very common that a tertiary graduate can earn only HK$9,000 a month and it is still too early for them to be kicked out of the social safety net. Many contribute to the family and are left with only HK$2,500 in their pockets. If the graduate had been on a student loan, then he has to pay back HK$900 a month, leaving him only HK$1,600 of disposable income for personal use and social activities.

"It would be much better if the young people could have more time to develop their careers and accumulate savings before they separate from the family. It would be just a matter of time before they could earn HK$12,000 or HK$13,000," Law said.

No matter what measures the administration adopts, it will take some time for public discussion. The Low Income Family Subsidy was proposed by Oxfam Hong Kong only in May this year. HKCSS proposed its low income supplements in August.

"This is one of the reasons why I don't think Hong Kong would get to becoming a welfare state. The public will debate it," Law said.

"Plus I don't think that Hong Kong people or Chinese people's values are there yet. Hong Kong people still believe much about fending for themselves rather than relying on others, even though there is a growing concern of their economic status," he continued.

"There are still things that we could do to change the current situation without resorting to tax increase," Law said.

Contact the writer at andrea@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 10/18/2013 page1)