Economy and Trade

Trailblazers of reform

By Xin Zhiming (China Daily)

Updated: 2011-06-01 10:09

|

Large Medium Small |

|

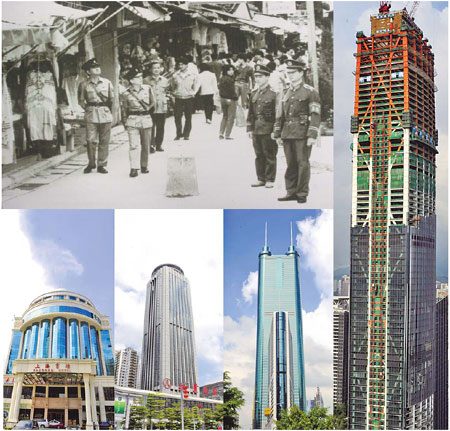

Top left: Chung Ying Street bordering Hong Kong and Shenzhen in the 1980s. The 250-meter-long commercial street was once a shopping paradise as thousands flocked to it for products that could not be found on mainland store shelves. Above: Landmark buildings of today's Shenzhen. Top Left: Xinhua; Above: Lu Haixin / Xinhua |

In the 1980s, when Li Zhongjian saw an expensive overseas-made cigarette lighter, he had the foresight to figure out how to make it in his home city of Wenzhou in East China's Zhejiang province. Li formed a company - something very rare in China then - to make the lighters, initially for the domestic market. At that time, China was just starting to shake off the shackles of the old planned economy and was starting to embrace a new one that later developed into a market-oriented economy.

Li soon found he could make more money selling the lighters overseas. As well, many other people in Wenzhou were also making and exporting lighters, turning the city into the base for lighter manufacturing in China. Indeed, at its peak in the 1990s, Wenzhou accounted for about 80 percent of the global market, with more than 3,000 manufacturers.

Nowadays, when commentators talk about the successes of Li and his compatriots from Wenzhou, they focus on the wealth of the country's first batch of entrepreneurs. But many may not know that wealth often comes at a price.

In late 1970s, China started to rethink its economic strategy after fierce discussion and debate, and embarked on building a market economy that would later change the global economic landscape.

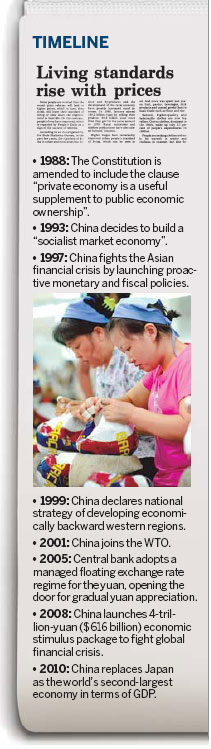

In 1981, the central government agreed on private individual businesses being established, saying they were "necessary supplements" to the economy.

In September 1981, the central government confirmed China would shift its focus to opening up and introducing foreign technologies and capital.

Meanwhile, the first signs of a market economy had been seen in some areas, including Wenzhou, when some audacious young men, China's entrepreneurial trailblazers, formed small businesses to sell various types of ironware and other products.

But this reform and opening-up road, however, proved very bumpy at the beginning of the 1980s due to ideological differences. The Wenzhou entrepreneurs encountered setbacks. Police tried to arrest the better known businessmen, or the so-called "Eight Magnates", accusing them of "playing the market", something similar to speculation and profiteering, which was a serious crime then.

Li, who was not one of them, still feels afraid, despite the fact they were released some years later. "We certainly felt uneasy and frightened back then," he says.

Nevertheless, China has managed to grow into a major economic power, with more than 9 percent annual growth rate over the past 30 years, the fastest among all major economies.

The reform and opening-up drive has brought wealth, but also changing ideas and ideologies as well as problems such as corruption, which provided ammunition for those who opposed reform. Reformers had to slow their pace and some people were uncertain where reform would head.

Against that backdrop, in 1992, the late leader Deng Xiaoping, who was then 88, made a historic visit to the southern regions, something symbolic in China's economic history as Deng used the journey to push forward the country's market economy reform.

Thanks to Deng's charisma, China's economic reform and opening-up - and its economic growth - accelerated. Since 1990, China's gross domestic product has been growing, peaking at 13.4 percent in 1993 before slowing to 9.7 percent in 1996.

The 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis tested China. China refused to depreciate its currency to protect the Asian economy and avoid triggering a chain reaction in the region. Exports slumped. Government expenditure was increased on a large scale and pro-active monetary and fiscal policies were implemented to bolster the economy.

With the new century, China accelerated integration into the global economic regime. In 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization, which further unleashed its foreign trade potential. In 2000, Chinese exports accounted for 3.9 percent of the global total; in 2008, they rose to 8.9 percent.

Problems, however, continued to ensue.

China's increasing exports, although based on comparative industrial advantage and meager profits, have led to trade friction with other countries. Trade measures, such as anti-dumping and anti-subsidy taxes taken by its trading partners, have posed serious threat to Chinese manufacturers.

Domestically, its snowballing trade surplus has led to a massive pile-up of foreign exchange reserves. Lacking proper channels for investment, China has invested much of the money in US debt and suffered serious losses as the dollar depreciated.

The eruption of the global financial crisis in 2008 made it more urgent for China to change its export-backed economic growth, and shift to a more consumption-driven growth model.

In 2009 therefore, China decided - when the country just began to step out of the fallout of the global recession - to transform its growth model.

And many foresighted people have taken the initiative to cater to the new policy platform and make money. Li Da, 24, is one of them.

The son of Li Zhongjian is betting on domestic demand instead of exports in which older business people like his father had indulged.

He graduated from a French university and, against his father's wishes to take over the lighter-making business, opened his own bakery, V. Seize Donut, last December, aiming to bring the original French taste to Wenzhou.

Li Da says what motivated his decision, aside from his liking for bakeries, is the change in China's economy. "This is a new industry (in China), and as the country's consumption picks up, there is huge room for its development," Li says.

Yu Ran in Shanghai contributed to this story.

(China Daily 06/01/2011 page4)

| 分享按钮 |