Society

Constant in a fast-changing society: Stress

By Peng Yining and Duan Yan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-05-21 08:19

|

Large Medium Small |

With an intense job market, high property prices and increasing cost of living, the pressure on Chinese citizens is growing every day, according to mental health experts.

Research shows that more people are suffering stress today than ever before, with crime and suicide rates on the rise.

"A certain amount of stress is constructive and healthy, but when it lasts too long or is too intense it will cause both mental and physical problems," warned Ren Xiaopeng, an associate professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' institute of psychology.

A study by the institute to test the mental health of 50,000 urban workers discovered that 60 percent were ya jian kang, or sub-healthy, a term common in China that describes a gray area between healthy and sick.

Also, 90 percent of the country's white-collar workers are stressed, according to a Tsinghua University investigation commissioned by Xinmin Evening News.

The nation's escalating house prices head the list of frustrations, closely followed by the costs of education, the fierce competition for jobs and the crowded transport networks.

However, despite the large number of people who admit to feeling the pressure, few actually seek professional help to reduce it.

"While one in 10 Americans will encounter situations where they need help from mental health professionals, most Chinese turn to their families and friends when they need help," concluded a recent report by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

To find out exactly how stressed China is, China Daily talked to four people in four professions - a surgeon, a chef, a real estate agent and a migrant worker housekeeper - to ask them how they not only handle the daily pressures, but also help others to do the same.

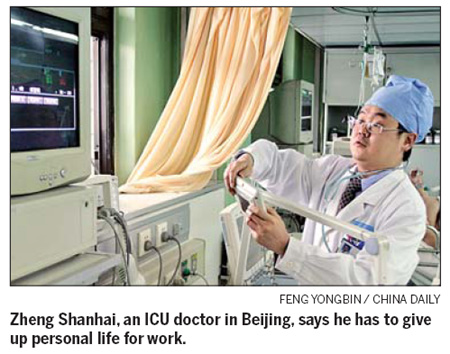

The doctor: Drama never stops in ICU

Zheng Shanhai's life is far removed from the doctors' portrayed in TV hits like House and ER. The 39-year-old, who works in the intensive care unit (ICU) at China Meitan General Hospital in Beijing, said he experiences "less dramatic successes and happy endings, and more annoying paperwork".

|

|

When Zheng was an intern in 1996, he went five days without once stepping foot outside of the ICU. He was one of only two doctors offering 24-hour care to four critically ill patients. "When I finally left the hospital, the sun made me dizzy," he said.

The medic, who has now been in the job for 15 years, recalled that he also once worked 36 hours without sleep to monitor a patient with pancreatic cancer.

"As an ICU doctor, you can't keep a regular schedule, at least during the first decade of your career," said Zheng. "Your life will always be interrupted with emergency cases. The doors of the ICU can be pushed open at any moment.

"To some extent, being a doctor means you have to give up your personal life, which include time with your family."

This year was the first time he was able to enjoy Spring Festival without once being called to the hospital to deal with an emergency.

Aside from the intense work schedule, the very nature of what doctors do - attempt to save people's lives - means he lives with a great deal of pressure. In ICU, doctors need to make split-second decisions and treat patients in critical condition.

On some occasions, Zheng said he witnesses three or four deaths a week. "As a doctor, it's very frustrating to watch people die," he said. "In most cases, the families of the deceased blame the doctor.

"There is a risk that when you see so much death you lose your compassion," he added. "I'm trying hard to not let happen to me. I think it's sad when medical staff lose their human kindness."

For Zheng, though, no matter how hard his day has been, he prescribes himself a good dose of sleep.

"There's nothing better to replenish your drained strength after the pressure of an exhausting day," he said.

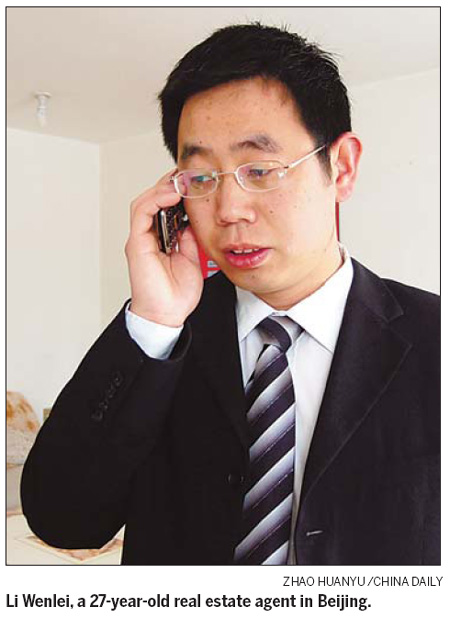

The real estate agent: No time for fun

As the property market continues to boom, putting prices out of reach for many people, the image of real estate agents in cities like Beijing and Shanghai has suffered a serious blow.

With a reputation for being unscrupulous, unrelenting and unabashed, real estate agents are among the most vilified occupations in today's society. This, according to health experts, has helped to make the job one of the most stressful in China today.

"I'm under a lot of pressure," said Li Wenlei, a 27-year-old realtor in Beijing, whose office windows are entirely covered with pictures of apartments for sale or rent. "The customers just don't trust us," he said before jumping out of his chair to talk to a couple inquiring about one of his properties.

Within seconds he had grabbed a bunch of keys and disappeared out of the door to show the couple the property. With more than a dozen rival agencies on his doorstep, Li needs to be quick on his feet. "We work from 9am to 10pm every day, and we don't get weekends. Yeah, sure, we give clients short messages at night or disturb them while they're working, but if we don't we might lose an opportunity," he said.

But Li worries about much more than his competitors.

"Buying or renting a house is very stressful," he said after returning to deal with more customers. (He was unable to sit down for any longer than a few minutes during the entire interview.) "As house prices keep rising, clients unload their frustrations onto us."

Following Beijing's tough measures to curb soaring property prices in recent weeks, Li also fears very soon people will stop buying.

Li has been a real estate agent for three years and now runs his own business. His main problem is not being able to hire enough staff to cope with demand. "People usually come to work for me for a year or several months. After that they either leave the business because they can't take the pressure or they are good and want to set up on their own," he said.

Although married with a 4-year-old son, Li said he gets very little leisure time. "I have no hobbies. Even if I'm away from my office, I will get lots of phone calls and can't really enjoy a vacation," he said in frustration. His weekends are spent mostly trying to reach deals with clients - or helping them to move in.

"After they've signed the contract, customers usually become easier to get along with," he joked. "Everyone is stressed nowadays, so lending a helping hand can alleviate the pain for all of us."

The chef: Can't stand the heat?

For 30-year-old Yuan Zhengsong, there is a basic fact of life: "If business is not good, the first one to be fired is always the chef."

|

|

Some 20 million people work in restaurants across the country, according to the China Cuisine Association, many of whom are "constantly changing jobs".

"It is probably one of the professions with the highest mobility in China," said Yuan, who owns a catering company in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province. "People are constantly losing their jobs and looking for new ones."

Yuan worked as a chef for eight years and he believes it is one of the most stressful jobs in the world. He now writes a blog for professional chefs to swap recipes, as well as post jobs and training opportunities, that regularly attracts 20,000 readers.

"I'm a chef, so I understand how stressful it is to be a chef," he said. "You have to be physically fit to handle heavy objects, and you are also standing and walking for hours."

Daily exposure to hot temperatures, smoke, unpleasant odors and loud noises can also lead to health problems, he said. "I quit smoking a long time ago because working in the kitchen is already bad for my lungs."

Family issues can also put pressure on chefs, said Yuan, who is single. "Festivals and holidays when families gather to celebrate, are the busiest times for chefs," he said.

Due to the competitiveness of the restaurant business, especially among chefs, China Cuisine Association urges employers to not only offer their staff training, but to also protect their mental health.

To help the kitchen staff cope with the stress, Yuan set up an online group on QQ, an instant messaging program, where they can discuss the problems they encounter in their work. "We have members across the country, and even some in other countries," he said.

Recent news reports on the poor hygiene standards or unethical practices of some Chinese restaurants - such as the reused cooking oil scandal - have also heaped the pressure on chefs.

"Some chefs would choose not to say anything (about the hygiene or other things) for fear of losing their jobs," said Yuan, who said his friend in Fushun, Liaoning province, was sacked 12 times in three years because he refused to cook dishes that included wild animals like pangolins and hedgehogs.

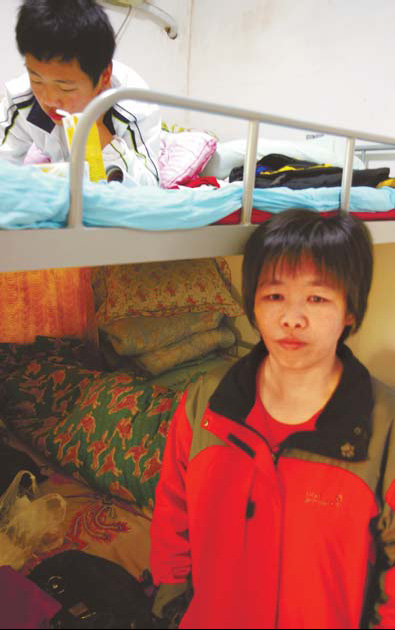

The migrant worker: Family comes ahead of happiness

Wu Chunli left Hebei province and moved to Beijing to work as an ayi - cleaner and babysitter - in 2006. At the time, her son was only 9 years old and had never been separated from his mother.

|

Wu Chunli has worked as an ayi in Beijing since leaving her hometown in Hebei province four years ago. The 38-year-old mother of one has only one hope - her 13-year-old son can have a better education than she did. [Peng Yining / China Daily] |

"I burst into tears when my first boss asked me to take care of their newborn twins," said the 38-year-old mother. "I missed my son so much."

Her husband used to be a migrant worker in Beijing until he was seriously injured in a construction site accident. Being the only breadwinner, she headed to the capital after being laid off by a grain plant in her native Gu'an county.

"I need the money for my husband's treatment and to pay my son's school fees," she said.

Migrant workers are among the most stressed members of Chinese society, according to health experts. Although they are generally only hired for menial jobs, their working hours can be punishing, while their salaries are often their family's income.

Wu's working day lasts from 6 am until 9 pm, during which she cooks, cleans and babysits for four different households. For her efforts she earns just 1,800 yuan ($260) a month. The only accommodation she can afford is a simple, 15-square-meter room that she shares with two other ayi.

Many boys her son's age (he is now 13) are already looking for work in cities "but I would never allow my son to quit his studies", said Wu. "I hope he can get into a famous college and find a good job. No matter how much hard work I have to do, I don't care. It's the only way he can change his life."

"I save every penny for my son," she said smiling.