Unique not universal

No civilization holds a monopoly on modernity; each is striving to pursue its own vision of human progress

US political scientist Samuel Huntington is best known for his "clash of civilizations" thesis, in which he argued that cultural and civilizational identities would become the primary sources of conflict in the post-Cold War world. This position was explicitly framed as a counterpoint to Francis Fukuyama's "end of history" assertion, which envisioned global convergence toward Western liberal democracy, free-market capitalism and secular rationalism. Huntington, by contrast, anticipated a world characterized by cultural and civilizational fragmentation, in which conflict would emerge along cultural fault lines rather than ideological ones. His thesis has profoundly shaped the global discourse on international relations, identity and the politics of culture for decades.

Yet another of Huntington's essays, The West: Unique, Not Universal (1996), should have received far more attention, especially in light of its contemporary relevance. In this essay, he offered a profound observation: Western civilization, despite its self-perceived superiority and global influence, is a "unique, not universal" model for humanity. Unfortunately, this work has received comparatively little attention, largely because such a strong and critical statement ran counter to the dominant post-Cold War intellectual paradigm of the unipolar time.

Huntington's argument challenged the ethnocentric tendency to equate Western values, institutions, and systems with universal human aspirations. He contended that Western ideational values, such as individualism, liberal democracy and free-market capitalism, emerged from specific historical, cultural and religious contexts unique to Western civilization. To presume that these values possess universal applicability, he argued, is not only intellectually arrogant but also politically dangerous, as it risks alienating non-Western societies and provoking cultural resistance.

In retrospect, Huntington's critical argument anticipated many of the geopolitical realities that now define the 21st century, including the erosion of Western liberal universalism and the relative decline of Western comprehensive power, the rise of emerging nations, the return of great power rivalry and armed conflict, growing economic dislocation and the backlash against globalization, and growing pluralism in global norms and values. Even within the West, liberal universalism has come under internal strain, challenged by the rise of populism, identity-driven politics and disillusionment with the unfulfilled promises of liberal globalization. The once-unquestioned confidence of post-Cold War triumphalism has given way to a more fragmented and contested world order.

These developments have converged into a series of global disorders: the intensifying strategic and technological rivalry between China and the United States, the Ukraine crisis alongside the emergence of a new "Berlin Wall" between Europe and Russia, the persistent wars in the Middle East, the spread of proxy conflicts and regional instability across Africa and the "Indo-Pacific", the worsening global energy and food insecurity, and the escalating climate-related disruptions that strain international cooperation. All these crises underscore how profoundly the Western-led liberal order has been weakened.

At first glance, these worldwide disruptions may appear to validate Huntington's "clash of civilizations" thesis, which interprets global disorder through a culturalist lens. Yet, a closer examination suggests that these developments more persuasively affirm his "West is unique not universal" argument — the erosion of the imposed liberal principle as a universal organizing model and the rise of a post-liberal pluralism in which diverse governance models coexist and compete. Notably, the West now frames China as a "systemic rival" — one that promotes an alternative political and economic governance model — rather than as a "civilizational rival" seeking to universalize Chinese cultural values and political norms, even though the two dimensions are closely interlinked.

Seen from this perspective, China presents a compelling contrast. As one of the world's oldest continuous civilizations and a rising great power, China has never sought to universalize its cultural or political model. Rather, it has consistently emphasized the particularity of its own development path. Modern Chinese history has been profoundly shaped by the process of "Sinicization" — the adaptation and integration of foreign ideas and practices within a Chinese political and cultural framework. Sinicization involves a dynamic process of selectively absorbing external influences while embedding them in indigenous values and traditions.

In this light, Mao Zedong's application of "Marxism to the Chinese context", Deng Xiaoping's "socialist market economy" and Xi Jinping's "socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era" all reflect a deep recognition that China's path to development and modernization is grounded in the country's unique historical experience, cultural heritage, and social realities. For any foreign idea or system to take hold in China, it must be internalized and Sinicized to align with Chinese conditions. China's modern trajectory demonstrates that it has been absorbing global ideas, such as Marxism, socialism, the market economy, modernization and modernity, while transforming them to suit its own context.

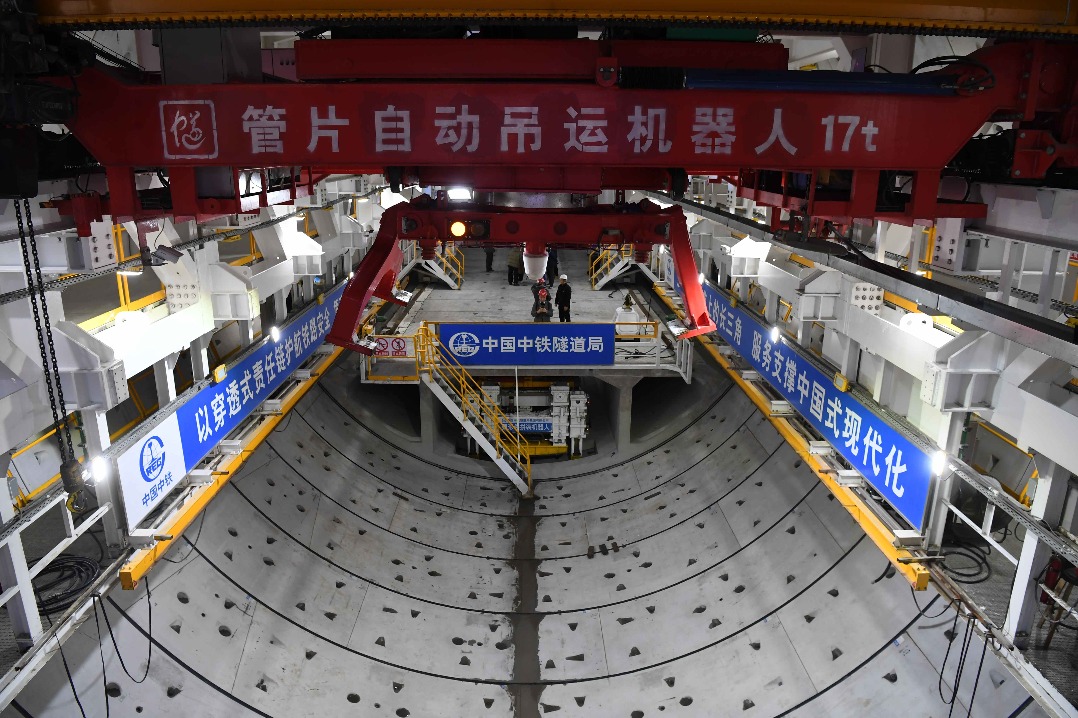

Over the past 40 years, China's economic reform has evolved through a gradual, adaptive and experimental process. While Chinese reformers have remained open to Western social, economic and financial theories, they have also realized that successful implementation requires the Sinicization of these ideas with selective adaptation and critical application to fit China's unique socioeconomic and sociopolitical realities. This creative transformation and innovative incorporation of external ideas have not only facilitated China's development but also enriched the original theories themselves, reflecting a spontaneous and self-reflective awareness of distinct social conditions, challenges and problems.

In the context of China's rise and the growing influence of the Global South, Huntington's insight that "the West is unique, not universal" may prove to be his most valuable contribution. His assertion proves the truth: no civilization holds a monopoly on modernity. While the "clash of civilizations" will remain a useful lens for identifying and analyzing sources of potential conflicts, the future world order will more likely be defined by civilizational coexistence — each striving on its own terms, and each pursuing its own vision of human progress.

Perhaps the central conundrum lies at the heart of Western liberalism itself. On the one hand, it champions tolerance, diversity and the coexistence of different value systems (pluralism); on the other hand, it asserts that its own principles, such as individual rights, democracy, the rule of law and free-market capitalism, possess universal validity (universalism). This contradiction increasingly exposes liberalism to a dilemma: Defending its universal ideals often conflicts with respecting the distinct cultural and political realities of other societies, weakening both its internal coherence and global legitimacy.

In conclusion, the West is and will still be one of the world's core power centers. Its current relative decline does not represent the collapse of Western economic, technological and political strength, rather it symbolizes a definitive end of the era of Western-driven "universalism", once celebrated as the "end of history". While the West still wields material and institutional influence brought about by its unique historical trajectory, its ability to shape the world order in its own image has diminished. This highlights that the West is unique, but it is not universal. Its model of modernity and progress no longer holds exclusive sway, giving way to a multipolar world where diverse civilizations chart their own paths.

The author is a Yunshan leading scholar and the director of the European Research Center at Guangdong Institute for International Strategies at Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, and an adjunct professor of international relations at Aalborg University, Denmark. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.