A miracle woven in silk

A five-year quest to re-create the Qingming Festival scroll has put the ancient craft back in spotlight, Zhang Yu reports in Shijiazhuang.

In a quiet workshop in Dingzhou, an ancient city in North China's Hebei province, a revolution was taking place, one silk thread at a time.

Under the steady glow of lamplight, the hands of master weaver Wang Pengwei guided a tiny shuttle through a forest of 20,000 vertical warp threads.

Each pass was a calculated move in a five-year-long battle to achieve the impossible — translating the ink-and-brush strokes of China's celebrated 12th-century scroll painting, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, into the shimmering, tactile language of silk tapestry weaving, known as kesi.

This monumental endeavor, an 8.2-meter-long kesi replica of the painting, has recently attracted great attention and reignited interest in the ancient art form.

After its debut on China Central Television's program China in Intangible Cultural Heritage in October, it garnered a staggering 300 million views online, pulling the 2,000-year-old craft of kesi from the quiet halls of museums into the vibrant, trending spotlight of social media.

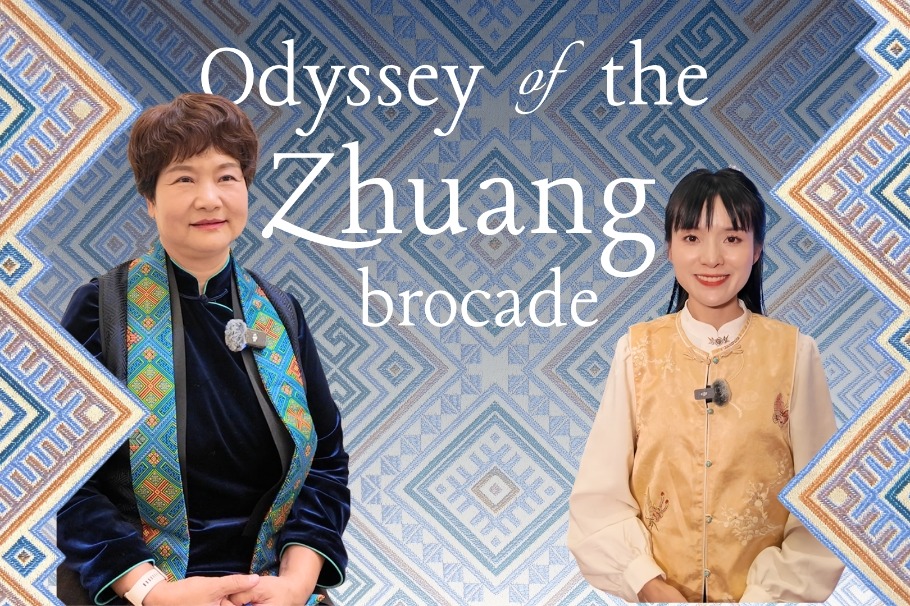

For Wang, the 57-year-old seventh-generation heir of the Dingzhou Wang family's kesi tradition, this was more than just a project. It was the fulfillment of a promise.

"The idea of creating a 'masterpiece for the ages' came from a deep respect for kesi," Wang says, her voice filled with quiet conviction.

"I've seen many artisans dedicate their lives to this craft. I always wondered, could I leave behind one piece that truly represents the pinnacle of this art? That would mean my life was not lived in vain, and I would not have squandered the skill passed down by our ancestors."

The choice of the Qingming scroll was deliberate.

Its sprawling panorama of more than 800 characters, numerous buildings, and bustling life details presented a peak no kesi artisan had ever dared to climb.

"Its unprecedented difficulty is precisely what made us determined to do it," Wang says. "If we were to do it, we would create the most exquisite piece."

The challenges were monumental. The original 5.28-meter-long painting had to be enlarged by 50 percent to allow the kesi technique to capture its most minute details.

A custom loom, 10 meters long, was built from scratch. However, the most profound challenge was human. Over 10 weavers had to work in perfect harmony.

"Each master's technique — the tightness of their weave, the density of the weft threads — was slightly different," Wang explains.

To achieve uniformity, the team underwent a grueling three-month training process, repeating the same weave daily until their collective output varied by no more than a single thread per centimeter.

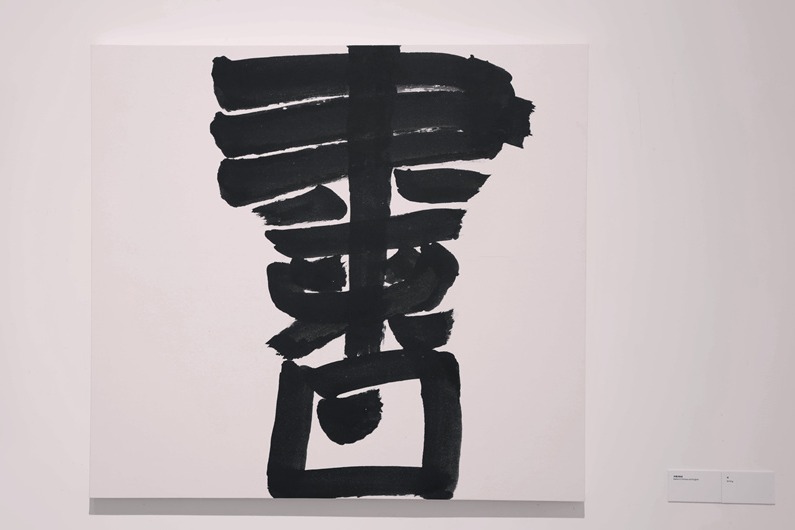

The soul of kesi lies in its defining technique: passing the warp and breaking the weft.

Unlike embroidery or regular weaving, kesi involves building up color areas with individual weft threads that are only woven where a specific color is needed.

This creates a distinct, carved effect, giving the craft its name, which literally means "carved silk".

Wang describes the process as "sculpting" with thread.

To create the robe of a single boatman, a shuttle — the tool used to carry the horizontal threads through the vertical threads on the loom — carrying dark silk would first outline the shape. Then, a shuttle with lighter-colored thread would fill in the body of the robe.

Where the shadow of a fold fell, a slightly darker thread would be introduced, using a technique called "long and short color graduation" to blend the hues seamlessly.

Each thread had to be pressed firmly into place with a bamboo tool, ensuring no color bled into its neighbor.

"For a few simple brushstrokes in the original painting, we might need a dozen shades of silk thread on a single warp line," Wang says.