Confucianism maintains bridge between two cultures

Echoes still felt today

"Confucianism forged a profound cultural alignment between the ancient Korean Peninsula and China, giving rise to a resonance whose echoes are still felt today," says Zhu Renqiu, a philosophy professor at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, Central China's Hubei province.

Zhu, who has spent decades researching the spread of Confucianism across East Asia, is a descendant of Zhu Xi (1130-1200), one of China's most influential philosophers, whose interpretations of the Confucian classics shaped education, governance and moral culture throughout imperial China for centuries.

According to Zhu Renqiu, Zhu Xi's philosophy, known as Neo-Confucianism, explored the moral structure of the universe and the cultivation of the self.

He argued that human nature and the nature of things share the same underlying principle, though only humans can act upon it. While the Four Beginnings — compassion, shame, deference and a sense of right and wrong — arise from principle, the Seven Emotions — joy, anger, sorrow, fear, love, dislike and desire — stem from material force and must be guided by principle.

Central to his thought was the nature of the mind, which unites principle and material force; moral cultivation, he maintained, requires investigation (gewu) to understand principle and purify the mind.

"These concepts, introduced to the Korean Peninsula by the distinguished scholar An Hyang, sparked debate among Korean thinkers for the next 500 years," Zhu Renqiu says.

In 1289, An Hyang accompanied the crown prince of the Goryeo Dynasty on a journey to Beijing, the capital of China's Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). While returning home the following year, he took with him a hand-copied version of Zhu Xi's vast collection of writings.

"It marked the beginning of a new intellectual chapter for his homeland," Zhu Renqiu adds.

At Sungkyunkwan — the highest educational institution of the time, whose former site in Seoul is now home to Sungkyunkwan University — An Hyang instructed his disciples in Confucian classics, on which they would later be examined to qualify for government service.

"At Sungkyunkwan, the coexistence of the Myeongnyundang (Hall of Ethics) as a school and the Daeseongjeon (Hall of Great Achievement) as a Confucian shrine symbolized this unity: while one trained minds, the other anchored their spiritual world in the ideals of Confucianism," says Lim Tae-seung, professor at the Academy of East Asian Studies at Sungkyunkwan University.

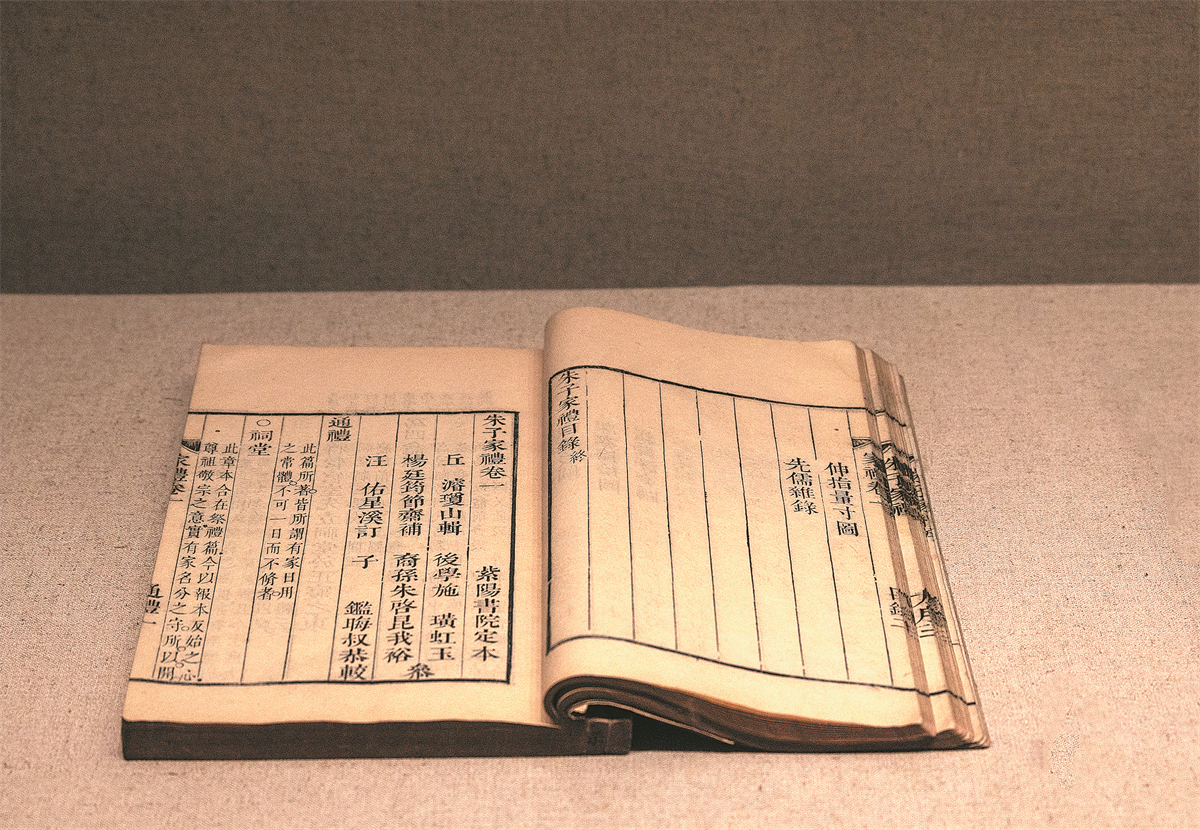

Reflecting on Zhu Xi's influence, Lim highlights Zhuzi Jiali (The Family Rituals of Zhu Xi), a manual compiled to codify Confucian rites for private households, which included weddings, funerals, ancestral sacrifices and coming-of-age ceremonies.