Symbolism sows the seeds of private, elegant landscapes

"One will always notice that as societies advance toward civility and refinement, people tend to build impressive structures before they learn to cultivate gardens with care and elegance."

This is a modern-English rendering of an observation English philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon made in his essay Of Gardens (1625).

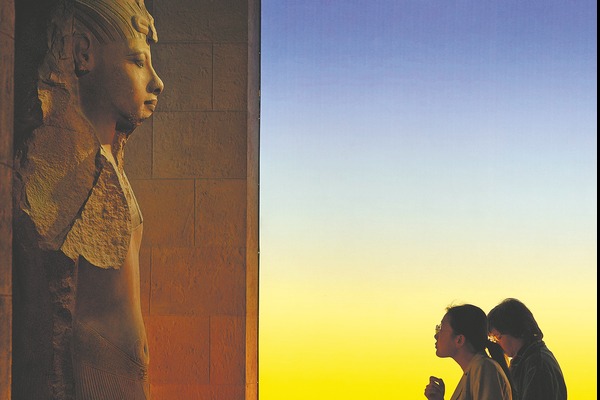

By all evidence, Bacon seems to have been right; the French admired the grandeur of the Palace of Versailles long before they celebrated Claude Monet's garden at Giverny, which, at a mere one hectare, is scarcely 1/800th the size of the sprawling estate commissioned by the all-powerful Sun King.

This pattern is evident not just in France, says Lyu Wentao, curator of Suzhou Museum's ongoing exhibition, From the Humble Administrator's Garden to Monet's Garden, in Suzhou, Jiangsu province.

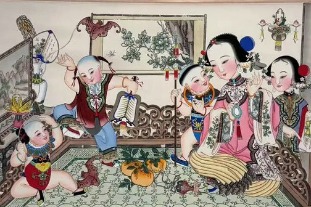

"Chinese gardens began as royal and noble pleasure gardens in the first millennium BC, often built on raised earthen platforms or enclosed within defined perimeters," he says.

"Often attached to palaces and royal estates, they served not only for leisure but also for ritual and symbolic purposes, projecting the rulers' authority."

Yet, a sense of resignation eventually began emerging and quickly gained appeal among China's scholar-officials, many of whom, having experienced the inevitable disillusionment of political life, ultimately chose to withdraw from public affairs. The garden, as a miniature natural landscape, became not only their refuge but also a symbol of resilience and quiet resistance — a subtle, silent form of rebellion.

Take, for example, Zhuozheng Yuan, or the Humble Administrator's Garden, built in the early 16th century by retired Ming (1368-1644) official Wang Xianchen. The humility he claimed to embrace was, in effect, a way of asserting moral superiority — even though his own character was somewhat open to question.

Another example is Canglang Ting, or the Pavilion of the Surging Waves, a garden that naturally took shape around a waterside pavilion. Built in the mid-11th century, it derives its name from an ancient poem composed sometime between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC.

The poem, Fisherman, declares: "If the waters of the Canglang are clear, I shall wash my tassels; if the waters are muddy, I shall wash my feet." At its heart, the verse is an allegory of a man's resolve to live by his own free will, whether in times of clarity or corruption.

Given the centrality of seclusion in Chinese literati culture, the same poem later inspired the name of another famed Suzhou garden, Wangshi Yuan, or the Garden of the Master of Nets. Here, the figure of the fisherman — "the master of nets" — became a powerful symbol of a recluse freeing himself from worldly entanglements for a life of quiet self-cultivation.

These three ancient Chinese gardens are in Suzhou, a city whose cultural sophistication rivaled its economic prominence as a trading hub from the 14th to the early 20th centuries.