Where olives and oranges speak across borders

On the flight to Athens, I noticed something round, glossy, dark brown in my lunch box. I popped it into my mouth, only to be hit by a wave of sour, salty bitterness. I gulped down water, but the strange flavor clung stubbornly to my tongue.

The woman sitting next to me smiled, "That's an olive. Very common in Greece."

I stared at the half-bitten fruit, each chew filling me with unease: how could this bitter little thing be a nation's culinary emblem?

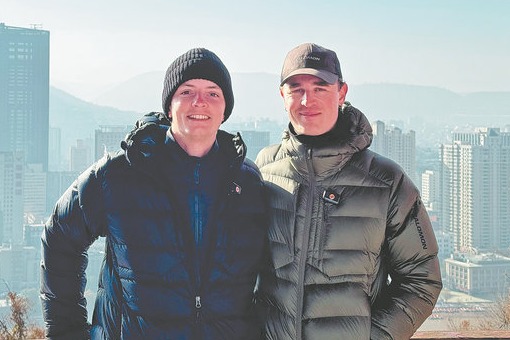

That awkward first bite marked the beginning of my summer study trip. On July 9, a group of 17 students and faculty members from Jiangxi Agricultural University set off for a two-week program in Greece.

It wasn't just sightseeing. For us — the future "agri-pioneers" — it was a journey of cultural and agricultural exchange. On that trip, I finally found the answer to my olive question.

At the University of Patras, a researcher welcomed us into the Chinese-Greek Joint Research Lab for Bioenergy and introduced the fruit: "Olives are rich in polyphenols — compounds that give the fruit strong antioxidant and lipid-protective qualities — sometimes even more than citrus." I thought to myself, this must be why olive oil is considered so healthy for cooking.

Later that day, another researcher projected photos of young people working in olive orchards near Lake Trichonida, blending olive oil with lavender essential oil and pouring the mixture into elegant pink-gold bottles for skincare products. Not just food, but beauty.

Suddenly, it clicked: this tiny olive carried more than a pungent bite. With creativity and science, each fruit could be deep processed into a passport to the world.

While innovation may begin in the lab, the real answer lies in the soil. We saw this firsthand when we visited the centuries-old olive grove by Lake Trichonida, where roots gripped rocky slopes and branches stretched over the cliffs.

The owner, her eyes shining with pride, explained that her family had tended the grove for generations, and handed me an olive to taste. This time, it was nothing like the dry one on the plane. It was fresh, juicy, and layered with flavor.

In that bite, I could taste her family's centuries of care — the harvests, the patient fermentation, the quiet craft passed down from one generation to the next.

I realized that while lab research and modern processing play an important role, they exist for one purpose: to let the quiet craftsmanship, devotion, and spirit of the land be understood and cherished more widely.

That day, I began to see what it truly means to be a new "agri-pioneer": rooted in the soil, yet reaching toward the world.

Youth exchange

Near the end of our stay, we joined the China-Greece youth exchange program at the Chinese Embassy. Minister-Counselor Lai Bo reminded us that young people are bridges of understanding. "Friendship among people strengthens ties between nations," he said.

As we said goodbye, Mariana, a Greek student who had once visited Ganzhou, a city in Jiangxi, told me, "I'm definitely going back just to have more navel oranges. They're so sweet and juicy. I couldn't stop eating them."

Suddenly, all the images came rushing back — the bitter olive on the plane, the lab lesson on deep processing, the grove's fresh fruit, the centuries of family craft. And now, one more: the taste of a Ganzhou navel orange lingering in Mariana's memory.

That was the answer I had been chasing all along: an olive becomes Greece's "taste totem" not just because bitterness can mellow into sweetness, but because the fruit bears the imprint of land, labor, and tradition — something the world can read.

A Ganzhou orange carries the same power. Its sweetness is more than flavor; it is the soil of Jiangxi, the craftsmanship of growers, the pride of a place.

Across mountains and seas, these flavors meet — and with them, people connect.

On the flight home, the stewardess handed me another tray with those familiar dark brown spheres. This time, I picked one up without hesitation. The tartness was still sharp, but now I could sense the sweetness hidden within.

Beneath the taste was something more — the whisper of terroir, the warmth of craftsmanship, the bond of exchange. The olive no longer felt foreign. It had become part of a larger story I finally understood.

Written by Nie Qi and Li Zijin, juniors majoring in English at Jiangxi Agricultural University.