A real gem of a story

Jade's appeal has moved emperors and symbolized their reigns, Zhao Xu reports.

Dual symbolism

Like many Chinese, Qianlong was captivated by the soft sheen and melodious tinkling of jade. A finely carved piece — a gossamer-thin jade bowl, for instance — brought him joy to behold and hold. At the same time, conscious of his Manchu heritage and the need to legitimize his reign, he recognized jade's cultural and political symbolism.

As crown prince, Qianlong wrote of jade's noble qualities, its gentle, understated luminance serving as a metaphor for a benevolent man. As emperor, he ensured a steady supply of raw jade for artisans both inside and beyond his court, sourcing it from Hotan (Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region).

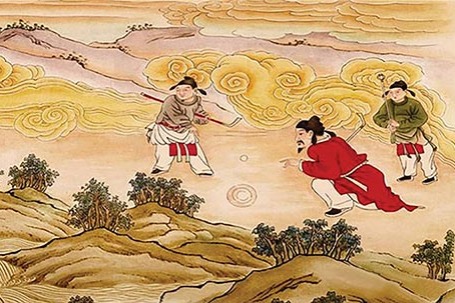

Hotan jade first came to the attention of a Chinese emperor through Zhang Qian, the 2nd-century emissary whose westward journeys laid the foundations of the Ancient Silk Road. Reporting to Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24), Zhang described a distant region where exquisite jade could be found along rivers or deep in the mountains.

From then on, Hotan jade traveled the Silk Road to imperial capitals. The enormous material and human cost of long-distance trade meant only the most precious commodities could justify the journey. It eventually found a patron in Song Dynasty (960-1279) Emperor Zhao Ji, whose bronze wares, depicted in the Xuanhe Bogu Tu (An Inventory of Antiques From the Xuanhe Era), became templates for jade artisans.One bronze wine vessel, in particular, may have inspired a Song Dynasty jade furnace now in Beijing's Palace Museum, its wooden cover and jade top likely added during the Qing Dynasty by an emperor.

That man was likely to be Qianlong. Separated from Zhao by six and a half centuries, Qianlong harbored mixed feelings toward the Song ruler, whose mismanagement had plunged Northern Song into chaos. In 1127, with Zhao already captive to northern Jurchen forces, the weakened Song court moved south of the Yangtze, marking the start of the Southern Song Dynasty, which endured 241 years before falling to the Mongols of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368).

Though Qianlong dismissed Zhao as unfit for the throne, he could not conceal his admiration for Zhao's artistic achievements, particularly his painting and calligraphy. Yet, the emperor he truly sought to emulate was Zhao, the great art patron. As historian Zuo Jun, also an expert of ancient Chinese jade from the Nanjing Museum, notes: "Given that Qianlong's ancestors were the Jurchen people — known as Manchus in the 17th century — his endeavors were calculated, tied to the projection of a political image."

Of the more than 40,000 poems he composed in his long life, roughly 850 were dedicated to jade, including 280 on antique pieces he had personally handled and admired.

"Qianlong's professed love of antique jades belied a sense of entitlement to China's cultural history, instilled by his literati upbringing," notes Zuo.