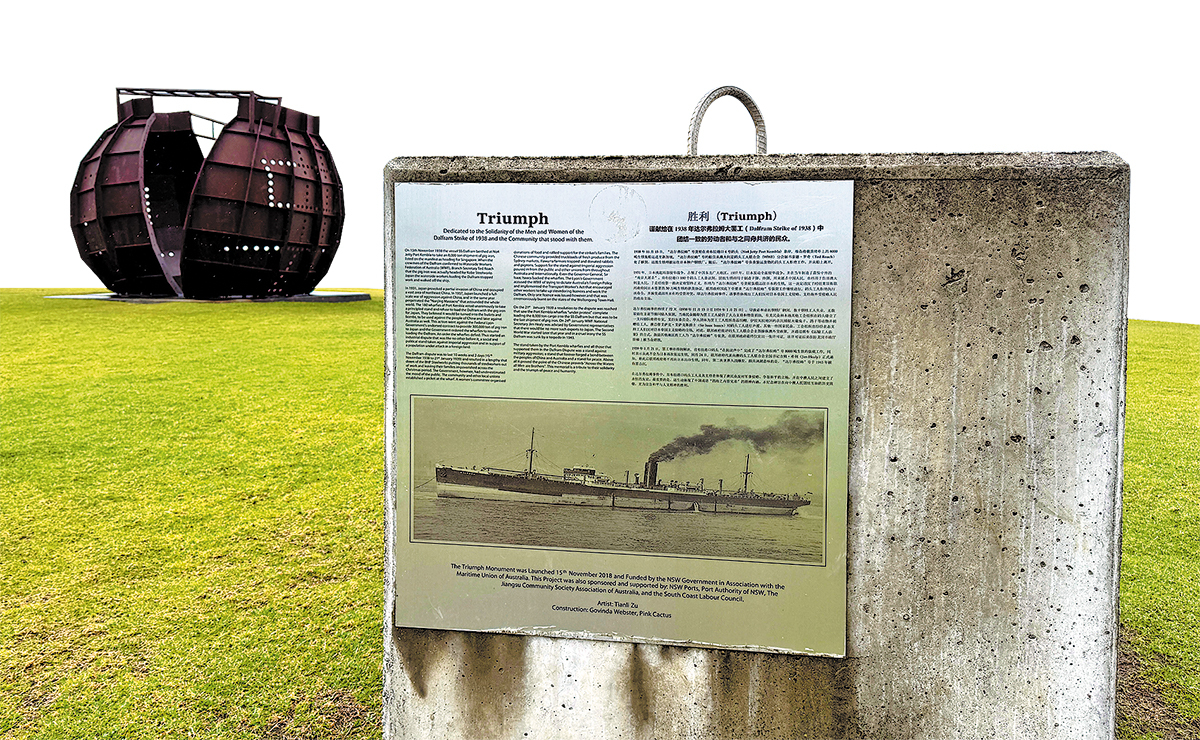

The Dalfram Dispute: when Australian workers stood with China

Historicindustrial action at port remembered amid 80th anniversary of victory against fascism

Common ties

The workers' actions at Port Kembla are widely lauded as a historic example of building peace and common ties across borders. Community leaders in Australia have pointed to its renewed significance amid events commemorating the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the World Anti-Fascist War.

Garry Keane, 70, former secretary of the southern New South Wales branch of the Maritime Union of Australia, told China Daily that it's timely to be reminded of the incident.

The maritime union traces its roots to the Waterside Workers' Federation, which was behind the campaign in Wollongong opposing the Japanese invasion of China.

During the dispute — with Australian workers' strong sense of solidarity with China and amid the broader anti-war sentiment — the Chinese community offered food and other support to the unionists, Keane said.

"The Chinese community in Sydney was very strong and they used to bring truckloads of vegetables from the markets down to the picket line where these guys (wharf workers) had nothing coming out of the (Great) Depression," said Keane, who was also deputy national presiding officer of the maritime union.

"It really did build a bond. This bond was forged during that time and it has been maintained over the past decades. We have a close association with the Chinese community," he said, adding that the Dalfram Dispute is commemorated every year on Nov 15 at the Port Kembla Heritage Park, joined by members of the Chinese community, with similar events to remember the Nanjing Massacre.

Arthur Rorris, 57, secretary of the South Coast Labour Council, Wollongong, told China Daily that the Dalfram Dispute was important in showing how workers led the way with their stand for peace.

"This changed the face of Australian unionism and it changed the face as well of collective efforts, with the relationships between the broader community and the union movement," said Rorris.

The dispute influenced Australian foreign policy in facing increasing hostilities amid the run-up to World War II. At the time, it was not long after World War I, and young people in Australia were split about going to war, he said.

"What had become apparent was that it's always the workers whose blood is spilled in a time of war. And they said, 'why should our blood be spilt for that?' Sometimes you do have to do that to defend your country, to defend a rightful cause, but not for the interests of imperialists and others.

"That is why the workers' action was so important and had a lasting change, because what they said is that'we will have a seat on that table where you make the decisions about who is our enemy and who is not'."

Rorris said it was very clear that the workers had a greater awareness of the world and the events unfolding in China.

He said the workers felt a greater alignment with interests and concerns of their brothers and sisters in China, than for the bosses who wanted to make a profit by sending iron to Japan, noting that Japanese attacks on Australia during WWII included the bombing of Darwin in northern Australia.

"What was done, how it was done, how it united all of the communities — the Chinese community, the broader Australian community, the workers here and abroad — these things are very significant, which is why we commemorate them," Rorris said.

The Dalfram Dispute ended in January 1939 with the stevedores going back to work, after union-government negotiations that included future pig iron exports.

"They ended up loading the Dalfram but that finished the trade of pig iron to Japan. It was Australian foreign policy (at that time) to sell the pig iron, though, knowing what was coming," Keane said. "But it was the action of those 180 waterside workers that actually changed the foreign policy and stopped that trade."