A decade in the making, dictionary mirrors shifts in language and culture

After a decade-long revision, the third edition of The English-Chinese Dictionary has returned — bigger, sharper, and more attuned to the rhythms of modern language.

Officially launched on May 8, the dictionary will be the highlight of the Shanghai Translation Publishing House at the upcoming Shanghai Book Fair, which will be held from Aug 13 to 19.

With 250,000 entries, the new edition incorporates updates that affect around 30 percent of its content. Prioritizing usability, it comprehensively covers both the English vocabulary and encyclopedic categories.

Published by the Shanghai Translation Publishing House, The English-Chinese Dictionary holds the distinction of being China's first large-scale, independently compiled bilingual reference book. It is also the official dictionary for translators working for the United Nations, according to Han Weidong, president of the publishing house.

The origins of this landmark project date back to the 1970s, when more than 100 English language professionals from 30 institutions — including Fudan University, Tongji University and Shanghai International Studies University — comprised the editorial team. Through extensive reading of newspapers and books, they amassed over 300,000 index cards, forming China's first English-Chinese corpus.

The first edition of the dictionary, which included 200,000 entries, was published in two parts. Volume one debuted in 1989 and volume two was launched in 1991. A compact edition was released in 1993, with a supplement published in 1999. The second edition was launched as a single volume in 2007.

Throughout its publication history, the dictionary has played an essential role in facilitating English education among Chinese speakers, and is widely used by students and professionals alike, according to Zhu Jisong, editor-in-chief of the third edition.

Zhu inherited the task from his mentor and predecessor, professor Lu Gusun (1940-2016) of the English department at Fudan University. Lu began to work on the compilation of the dictionary as early as the 1970s. From 1986, Lu served as the editor-in-chief of the dictionary's first and second editions.

Under Lu's encouragement, Zhu began work on the third edition in 2014. "I had a somewhat ambitious plan for the third edition," Zhu says. "I wanted to highlight the creativity and productivity of modern English since the 15th century. … I believe a more sophisticated understanding of English can help China expand its knowledge of the world."

Apart from the routine tasks of any large-scale lexicographical update, such as correcting errors and including neologisms, Zhu and the editing team at the Shanghai Translation Publishing House set out to enrich the dictionary with illustrative examples drawn from diverse and contemporary sources, both written and spoken. This shift, Zhu explains, better captures the dynamic, ever-evolving character of English.

However, Zhu and his colleagues were faced with a very different situation from their predecessors. "Few teams for professional research and the compilation of dictionaries remain in Chinese universities today," Han says. "While some scholars may take it as a subject for their research, few actively participate in dictionary-making."

To overcome this, Zhu and the Shanghai Translation Publishing House launched a new Readers' Integration Project, recruiting volunteers from all walks of life to contribute new words, phrases and uses of English-Chinese translation in their specific professional field, academic background and reading experience.

Many contributors connected via a WeChat group called Shanghai Morning Herald, which grew over the years into a network of more than 10,000 members. These citizen lexicographers submitted new words, translation examples, and even flagged outdated definitions or blind spots in the dictionary's previous versions.

Their input ranged from terms like "cumin", a Mediterranean herb, to "euglycemia", a medical term meaning normal blood sugar level, and cultural items like "Amber Alert", a North American system for locating missing children.

These "interested individuals", as Lu fondly called them, "filled the blind spots of the editing team, pointed out potential flaws and defects, and expanded the scope of entries included in the dictionary", says Zhang Ying, head of the English-Chinese Dictionary compilation department at the publishing house. The Readers' Integration Project has become an important force in the dictionary's compilation, and "will be implemented as a permanent system in the future editorial work", she says.

"We compiled The English-Chinese Dictionary Third Edition from the perspective of Chinese scholars and language learners, aiming to demonstrate how to express Chinese culture in authentic English," Zhu says. To achieve this, the editorial team "handpicked expressions from classical Chinese, and the Cantonese and Shanghai dialects, in the belief that despite vast differences between the two great languages, Chinese and English can make a tremendous match in the dictionary", Zhu writes in the preface to the new English-Chinese Dictionary.

The dictionary also tracks the growing influence of Chinese culture and presence in English usage. "This ensures that the dictionary serves not only as a record of interlingual equivalences but also as a reflection of China's prominent and constructive role on the international stage," he says.

Today's Top News

- Expanding domestic demand a strategic move to sustain high-quality development

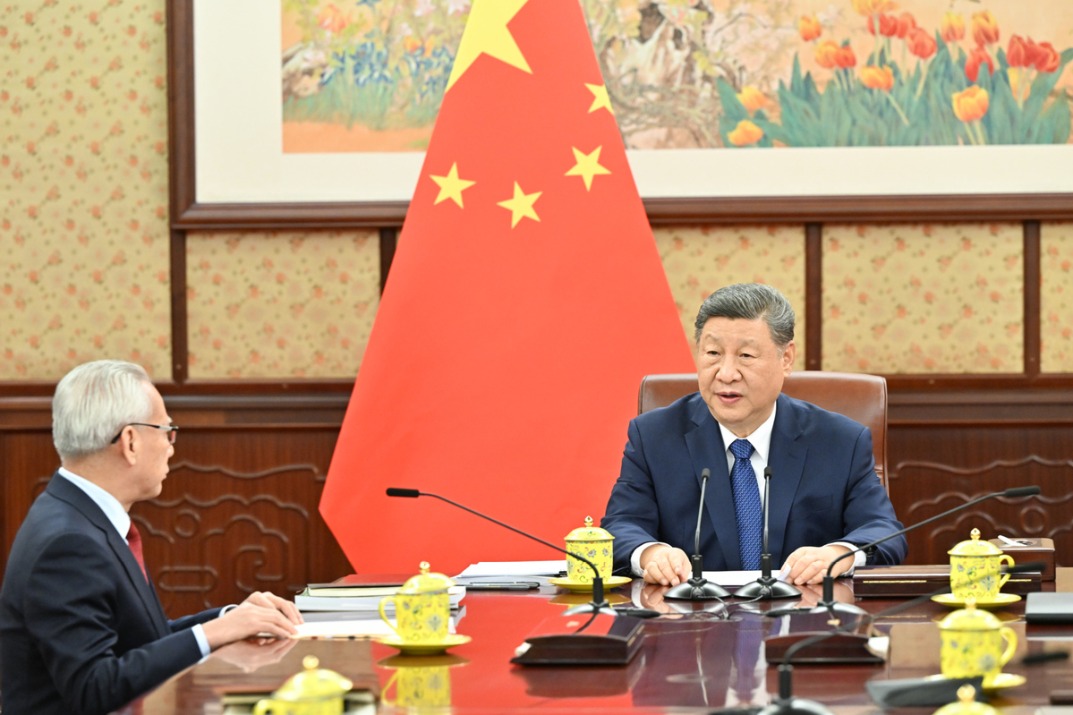

- Xi hears report from Macao SAR chief executive

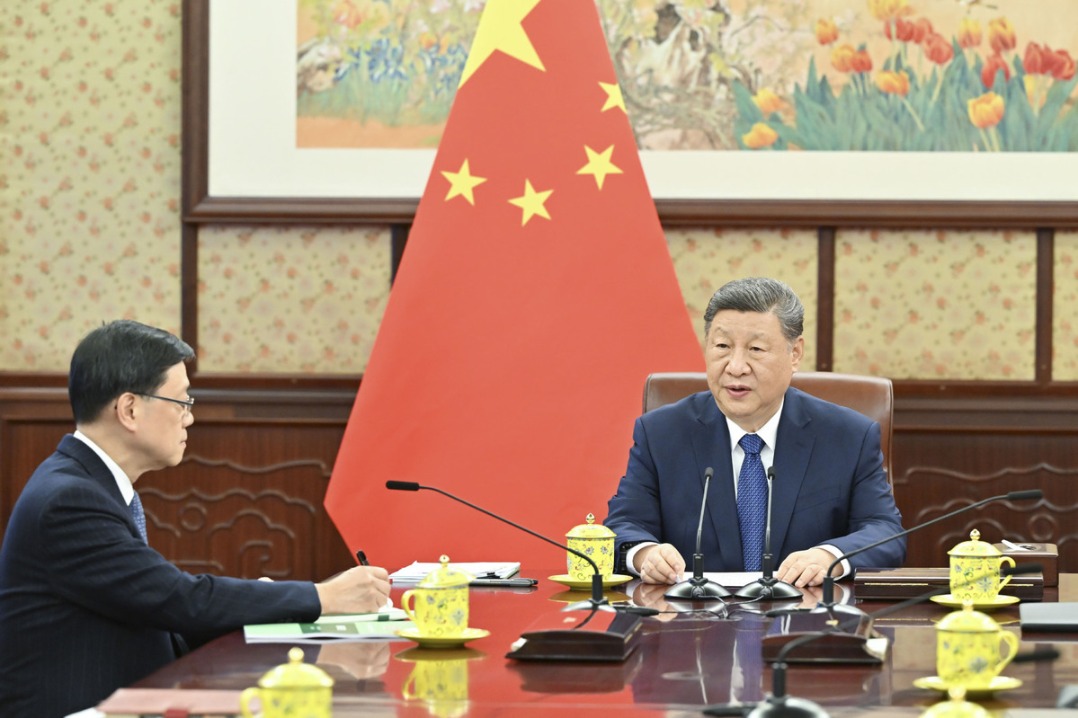

- Xi hears report from HKSAR chief executive

- UN envoy calls on Japan to retract Taiwan comments

- Innovation to give edge in frontier sectors

- Sanctions on Japan's former senior official announced