A testament to courage and resistance

Brutality by Japanese invaders haunts elderly survivor of mass graves who vows to keep memory of atrocity alive, Wang Qian and Zhu Xingxin report in Datong, Shanxi.

Beneath the biting wind sweeping across the coalrich regions of Shanxi province lies a testament to unspeakable brutality. At 92, Qian Kuibao's voice trembles not with age alone, but with the weight of memories. His scarred scalp tells a story that words cannot fully capture — a story of survival from one of Datong's mass graves, where the bodies of tens of thousands of Chinese miners were dumped during the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45).

"I was badly injured, unconscious. The Japanese threw me, still breathing, into the mass grave near the Chenghuang Temple at Silaogou mine," Qian says of his memory back to the winter of 1941.

"It was deep winter. Freezing, near death, I crawled out when they left. I collapsed on the miners' path. That's where Qian Ziming found me." Rescued by a kindhearted miner from Hebei province, Qian Kuibao, once known as Wang Jiuxiang, adopted his savior's surname, bearing witness for those who perished.

His survival was a grim miracle. "Of the 300 fellow villagers crammed into that train carriage with my family … only my cousin and I lived past that Chinese New Year," he says. "I do not live for myself. I live for those 300. I live for the tens of thousands of people killed by the Japanese. As long as I breathe, I will tell this truth."

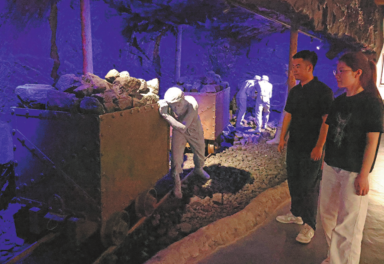

About 18 kilometers southwest of Datong, within the somber confines of the Datong Mass Graves Memorial, a complex of the coal pits that were used as dumping sites, the scale of the horror crystallizes. Guide Wang Ruoyun, whose childhood was shaped by school visits to the site, gestures toward the haunting exhibits.

"From 1937 to 1945, the invaders looted coal at any human cost," she says. "They seized more than 14 million metric tons of coal (in Datong). The price was over 60,000 miners' lives. For every 1,000 tons torn from the earth, four men died," she says.

From September 1937 to August 1945, during the Japanese occupation of the coal mines in Datong, the invaders ruthlessly plundered coal resources and forced workers to labor under brutal conditions and harsh living environments. Under their control, the coal production in Datong increased from 870,000 tons in 1938 to 2.27 million tons in 1942, according to the museum.

Many miners, who were either killed or left on the brink of death, were discarded in desolate areas, riverbanks, valleys and abandoned mine shafts, creating over 20 mass graves filled with bones.

For the museum's director Guo Dianjun, the mass graves site stands as a witness to Japan's policy of "exchanging blood for coal". Officially opened in 1969, the museum spans 68,000 square meters, with a black granite memorial wall inscribed with the numbers 14,000,000 (tons of coal looted) and 60,000 (lives lost).

Its five exhibition sections trace Japan's invasion, coal plunder, laborer enslavement, and postwar remembrance with immersive displays including reconstructed mass graves, survivor testimonies via holograms, interactive media, and excavated artifacts. There are more than 300 file photos and about 80 relics.

Due to limited domestic supplies of natural resources, such as coal, iron ore and oil, Japan looked to Datong to secure access to coal after its rapid industrialization during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

According to Wang, during Japan's occupation of the city, Japanese invaders forcibly conscripted laborers from famine-stricken regions like Henan and Hebei provinces under false promises of job opportunities.

The mass grave at Meiyukou south gully is a well-preserved and large site witnessing the atrocity, featuring two caves filled with layered skeletal remains. The upper pit is about 5 to 6 meters wide and more than 40 meters deep. The lower pit is about 3 to 4 meters wide and over 70 meters deep.

In 1966, researchers began the process of clearing and identifying the remains in the two pits at Meiyukou. They conducted detailed examinations of the conditions and ages of the remains with about 200 sets of bones excavated and cleaned. The average age of the deceased miners was 32.8 years old, with the oldest being 56 and the youngest 16, and there were no females in the pit.

During the clearing process, the facial expressions of some of the remains were clearly visible. Some of the deceased miners appeared to be struggling to crawl toward the cave entrance, some were touching their wounds, some seemed to be calling for help with their mouths open, and others showed expressions of fear, pain and despair.

"Seeing the actual remains at the heritage site is profoundly shocking. It must be seen," Guo says, adding that they need to deepen the research and harness new media to amplify this history to visitors from home and abroad.

He emphasizes the museum's dual purpose: mourning victims while championing peace through intergenerational education, particularly because this year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War.

The Japanese invaders' ruthless plundering of the coal resources and their brutal rule and persecution of the miners provoked widespread anger and resistance among the workers, who launched an unyielding struggle against the occupiers. They sabotaged tools and equipment, caused production stoppages, engaged in passive resistance, went on strikes, conducted secret armed struggles, and punished collaborators. The persistent resistance of the miners repeatedly thwarted the Japanese invaders' plundering plans.

Detailing the evolution of resistance, Guo says that from spontaneous acts of defiance by workers and locals to organized sabotage and strikes under the Communist Party of China, those years were a crucible of struggle for freedom.

Despite its profound significance, the museum struggles for recognition. "The Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre by Japanese Invaders in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, is widely known, and rightly so," Wang says. "Our story here, though equally vital, remains lesser known. Fewer visitors came in the past … I want to tell more people. This place represents the plunder of Datong's resources — it's a microcosm of the history."

Guo echoes: "Our core purpose is peace through remembrance. We must pass on this history to the next generation."

To Qian Kuibao, the museum is more than just a repository of bones, but a living call to confront the darkness of the past, to honor the silenced, and to tirelessly defend the peace bought with unimaginable sacrifice.

Today's Top News

- Xi sends congratulatory letter to forum dedicated to the International Year of Peace and Trust in Turkmenistan

- China to host 33rd APEC Economic Leaders' Meeting in Nov

- Strengthening domestic demand central to China's new five-year plan

- China's grain output tops 714 million tons in 2025

- China proposes theme, priorities for 2026 APEC 'China Year'

- Reforming consumption rules to fully unlock spending