Measuring up a tall task for science

Fifty years ago, China announced its first precise measurement of Mount Qomolangma, also known as Mount Everest. Nowadays, China's ongoing measurement missions in the region remain important in understanding the evolving conditions on the world's tallest mountain.

China's persistent measurements provide precise elevation and location data that serve as a critical global benchmark for global geographic information systems and topographic mapping, ensuring the world's maps stay accurate, said Chen Gang, a professor at the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan). He noted that Mount Qomolangma grows a little every year.

The data aids in understanding plate movements and crustal deformation, while supporting critical research in geology, geography and meteorology, as well as applications in resource exploration and environmental conservation, Chen added.

"Qomolangma is more than a mountain — it's a natural laboratory," he said, explaining that the mountain stands as a sensitive indicator of Earth's activity, that drives scientific breakthroughs and thus attracts global research attention.

"Our work here supports everything from disaster prevention to navigation systems worldwide," he said.

Beyond science, many countries conduct measurements of Qomolangma to test and showcase their cutting-edge technologies. Thus, the mountain has become a stage for demonstrating technological prowess, according to Chen.

From 1975 to 2020, China's measurement techniques, evolving from traditional geodesy to using the Beidou navigation satellite system, enabled a high degree of precision in determining Mount Qomolangma's height, with each result accurate to two decimal places, Chen said.

Precisely measuring Qomolangma upholds national sovereignty. "The north slope lies within China's borders, so it is our right and responsibility to measure and publish its height," he said.

Measuring the peak is akin to measuring a person's height. "We first establish where the foot is, then measure the distance to the head," Chen said.

Scientists use Earth's mean sea level as the base, with China adopting the Yellow Sea's average level as its reference, according to Approaching the Top of the Earth, a popular science book compiled by the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center and other institutions.

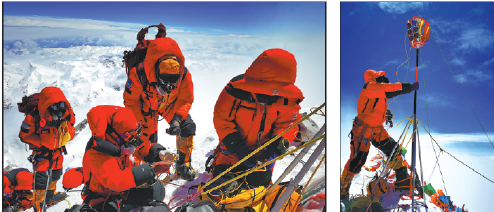

The survey team then ascends with instruments, synchronizing measurements with climbing efforts, Chen said.

The surveyors need to carry fragile instruments as they ascend, making the task of climbing the mountain more arduous.

Sometimes, repeated trips are needed — like in 2020, when snowfall forced three attempts. Despite such setbacks, the repeated journeys often net better results, Chen said.

The professor noted, however, that without climbers fixing ropes, setting up camps and providing supplies, the task would be much harder.

During breaks in the weather, the team deploys a survey beacon to the summit and the Beidou system, Chen said.

The beacon, equipped with red prisms, allows six ground stations to measure distances via laser reflections, enabling triangulation. This ensures data collection continues even after the team descends, he said.

To ensure precision, multiple techniques — including global navigation satellite systems, leveling, photoelectric distance measurement, satellite remote sensing and gravity surveys — are combined. Rigorous calculations and verification yield the final elevation — 8,848.86 meters as of data released in 2020.

Today's Top News

- Xi Story: Under Xi, China's first 15-year city plan resonates far

- Chinese premier lands in Rio de Janeiro for 17th BRICS Summit

- China to strengthen disaster management

- Xi's letter uplifts nation's young people

- Actor hailed for joining CPC at 92

- Sino-German ties set to be strengthened