Decoding the sands of time

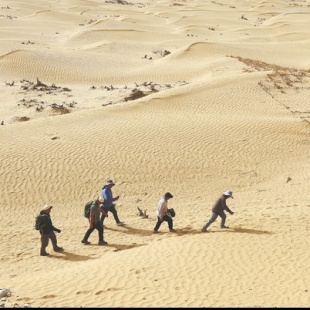

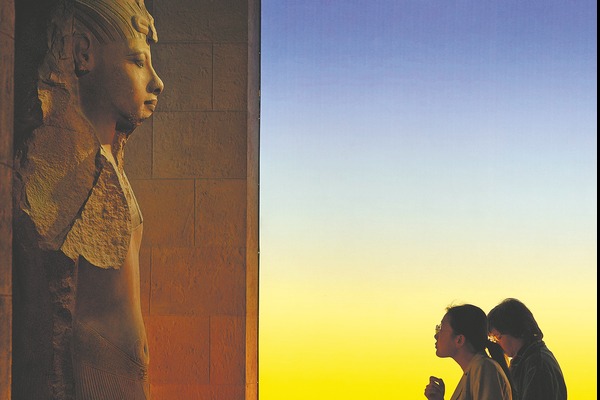

The first time Matkasim entered the desert for archaeological studies was in 1990, when he followed Ediris to study the Niya ruins, remains of Jingjue state on the ancient Silk Road from the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD. Since then, he had participated in multiple desert archaeological studies under the guidance of Ediris, and has grown into a mature desert archaeologist.

"Working in the desert is so arduous that I have considered giving it up, since we often had to stay in the desert for 20 or 30 days," says Matkasim. "I guess I could persist because I still love the work, the surprises of seeing ancient sites are always impressive."

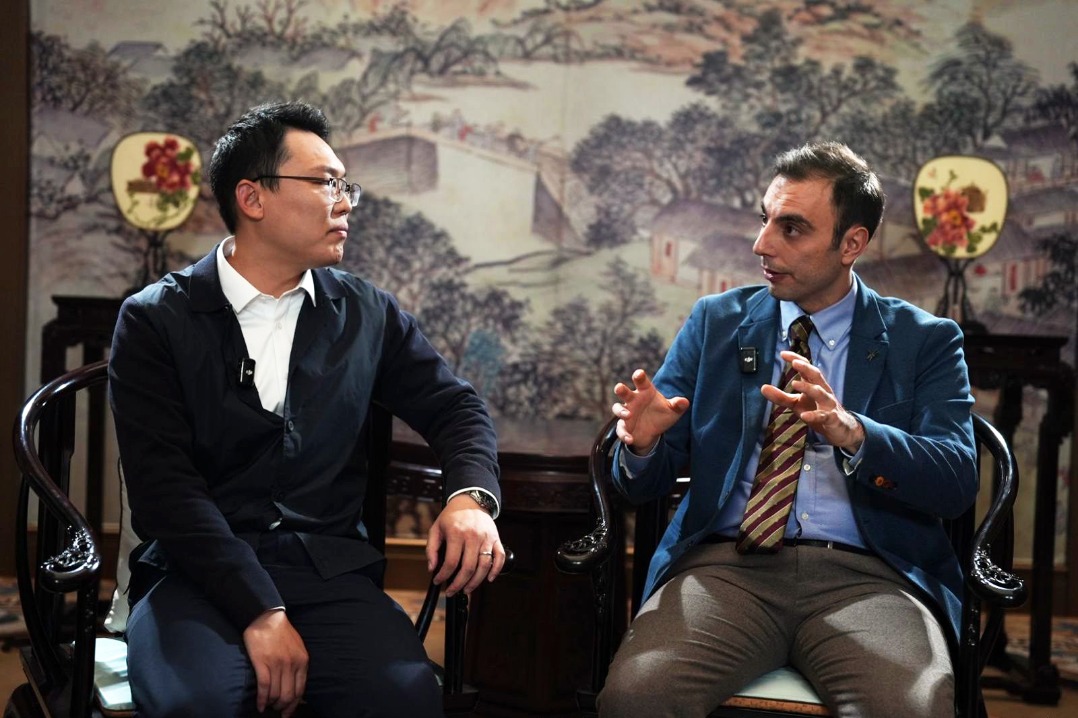

He has learned a lot from Ediris. "His conscientiousness and attention to details have greatly influenced my style of work.

"When organizing an academic trip to the desert, he always considers every detail, down to reminding us of taking away cigarette ash. Learning from him, I was very careful when I led the teams. Over the past 35 years, my teams have remained accident-free as well," he says proudly.

On Jan 1, Matkasim retired from the culture and tourism bureau of Hotan prefecture, but he agreed to help complete the census work until next year. He has imparted much of his experience in the desert to Matyvsup, a young member of the team.

"Before this census, I worked in the Hotan Museum and was engaged with display design," says Matyvsup. "I had never had a chance to see cultural heritage in the desert as a local of Hotan. Therefore, I have been very excited participating in the census work, which allows me to have hands-on experience working in the desert.

"I treat Matkasim as my teacher. I have not only learned professional knowledge from him, but also his experience living and working in the desert, which can hardly be taught without practice. Now he has retired, and I will carry on the torch to give full play to what I have learned," he adds.

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn