Village keeps cultural heritage flourishing

Traditional ways of life preserved by dedication of inheritors, Yang Feiyue reports in Jiaxing, Zhejiang.

On the banks of a slow-moving river in Shengfeng village, the rhythmic knock of wood against wood has been echoing in the hall of Zhang Laisheng's workshop as the sun emerges on the horizon.

Though small in size, his workshop hosts boat molds of various shapes and sizes that either lean against the wall or rest on the shelves for close appreciation.

With chisels and hand drills, the man in his 70s demonstrates the ancient craft of local traditional wood boat building before a group of curious visitors to the waterside village in Jiaxing, East China's Zhejiang province, in late April.

"The hardened wooden planks must be polished to a smooth sheen, with every joint precision-cut for perfect alignment," explains Zhang, who has spent six decades coaxing river-worthy vessels from stubborn camphor, fir and pine.

His boatbuilding journey began when he was just 16, apprenticing under his father at the village boatyard.

"Practically everyone had to rely on the boats to navigate their way to Shanghai, and Suzhou and Kunshan in Jiangsu province in the old days," he recalls.

"First thing I learned was how to lay the keel," he notes, brushing sawdust off his sleeve.

"You get the keel wrong, the whole boat is off. You don't just build a shape — you build a life raft."

Used by fishermen, farmers and ferrymen, the boats have gradually been put out of service, as concrete bridges span where ferries once glided and modern transportation takes over.

Yet, Zhang is not ready to let go of the trade that has accentuated his whole career and was named a city-level intangible cultural heritage in Jiaxing in 2009.

Between the conversations with his guests, his calloused hands and sharp eyes execute measured movements.

The master shipwright begins by selecting carefully curved wooden planks that match the vessel's intended dimensions.

These are meticulously shaped and fastened to the central keel plank, establishing the boat's fundamental structure. The bow and stern are then installed, completing the hull's framework.

A critical step follows with the installation of the lazi — gracefully curved sideboards that serve multiple functions, he emphasizes.

"These elegant elements provide essential stability during navigation while simultaneously acting as catwalks for boatmen poling from stem to stern," Zhang explains.

Additionally, beyond their practical purpose, the lazi sideboards add distinctive decorative flair to the vessel. The deck is then laid to complete the main structure.

The craftsman then painstakingly seals all seams using a traditional mixture of paint and plant fiber paste, ensuring complete watertight integrity.

For the cabin and superstructure, fragrant fir wood remains the standard choice, though prized vessels may feature more luxurious materials like cypress, yellow oak, or even rosewood.

"Fir wood is mainly used for its flexibility, moisture resistance, rot-proof quality, lightweight nature and excellent buoyancy," Zhang says.

A protective coating process follows, with tung oil applied to the hull (particularly below the waterline) to prevent rot, while painted finishes adorn the upper structures.

While wooden boats have largely disappeared from practical use, their cultural significance endures. The tourism industry's growing demand for authentic pleasure craft has created new relevance for these waterborne treasures.

Rejuvenating customs

About three years ago, Zhang was invited to set up a shop at Linglongwan, a tourist site near the river, to keep the tradition alive and use it to spice up the experience for travelers by making scaled boat models through traditional techniques.

While Zhang's "boatyard" is a must-see, it's just one thread in the cultural tapestry of Shengfeng village, where winding paths and stone bridges arching over the river lead to ancestral halls etched with fading calligraphy.

The village embodies the quintessential water town of Jiangnan — the region along the lower reaches of the Yangtze River — characterized by houses with whitewashed walls and black-tiled roofs.

This once-obscure village has undergone a remarkable metamorphosis, emerging as a provincial exemplar of rural cultural tourism through strategic preservation of intangible cultural heritage, according to local authorities.

Shengfeng closed down over 400 pig farms, clearing the path for ecological restoration efforts over time. Concurrently, art projects that accentuate local cultural heritage have been initiated to enhance the tourism experience.

Over 200,000 visitors came last year, contributing more than 3 million yuan ($413,000) in collective income for villagers, a testament to the village's successful "culture-plus-tourism" development model, according to local officials.

The Linglongwan site has served as the heart of cultural experience in the village.

"Beyond the celebrated boatbuilding, visitors discover cultural charm behind local sugar cake, farmers' paintings, and a pigsty-turned-ceramics studio where a Jingdezhen-trained potter gives class," says Ding Weizhe, who is in charge of the site operations.

"We're seeing exceptional foot traffic in April," Ding notes, referencing a national farmers' painting biennale that drew in artists from across the nation on April 20.

Weekends see families enjoying public lawns, while weekdays host study groups examining Shengfeng's successful rural vitalization model, Ding says.

Within walking distance from Zhang Laisheng's workshop, Zhang Jinquan is also guarding the centuries-old tradition of sugar cake mold carving — an intricate folk art that blends woodworking, paper-cutting and spiritual symbolism.

Delicate craft

Now in his 70s, Zhang Jinquan has dedicated over 50 years to perfecting this delicate craft, also recognized as Jiaxing's intangible cultural heritage in 2009.

The art form dates back to at least the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), originally created to produce decorative rice cakes for festivals, weddings and ancestral worship.

Zhang Jinquan learned the craft as a teenager from family members, painstakingly copying traditional patterns like the "three sacrificial animals" motif featuring a pig's head, carp and rooster.

"In hard times, these sugar cakes replaced real sacrificial offerings," Zhang Jinquan explains, recalling how poor families during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) used the imprinted cakes in place of actual meat during religious ceremonies.

Each mold begins as a block of camphor wood, the preferred material for its resistance to cracking.

With practiced hands, he transforms these raw materials into functional artworks, typically completing three molds in a day that sell for about 35 yuan each.

The process demands absolute precision.

"The challenge lies in replicating every detail of the ancestral designs exactly. One wrong cut can ruin the whole piece," he says.

To appeal to young people today, he has continued to innovate, creating contemporary designs like his popular Zodiac series and collaborating with local institutions on various themed molds bearing slogans like "Obey the Law" and "Never Forget Our Mission".

Now semiretired, Zhang Jinquan splits his days between carving and teaching, determined to preserve this slice of cultural heritage in the Jiangnan region.

"As long as there are people willing to learn, I'll keep teaching," he says.

"These patterns carry our history, and they deserve to be remembered."

Like Zhang Jinquan, the boat maker Zhang Laisheng has also actively been answering the call to build new boat models or restore ancient ones across Jiaxing, in his efforts to preserve the tradition.

Apart from the time at the boat-making workshop, he has also taught local youth, visiting design students, even curious travelers.

"Some come seeking to learn, while others just want to feel the tradition," he notes, adding that he would hold no reservations about imparting the details of the craft.

"It won't last unless we pass it on," he says.

"It's my way of clinging onto a big part of my life, the part that I've been familiar with for so long."

Today's Top News

- Foreign ministers of China, Egypt call for Gaza progress

- Shield machine achieves Yangtze tunnel milestone

- Expanding domestic demand a strategic move to sustain high-quality development

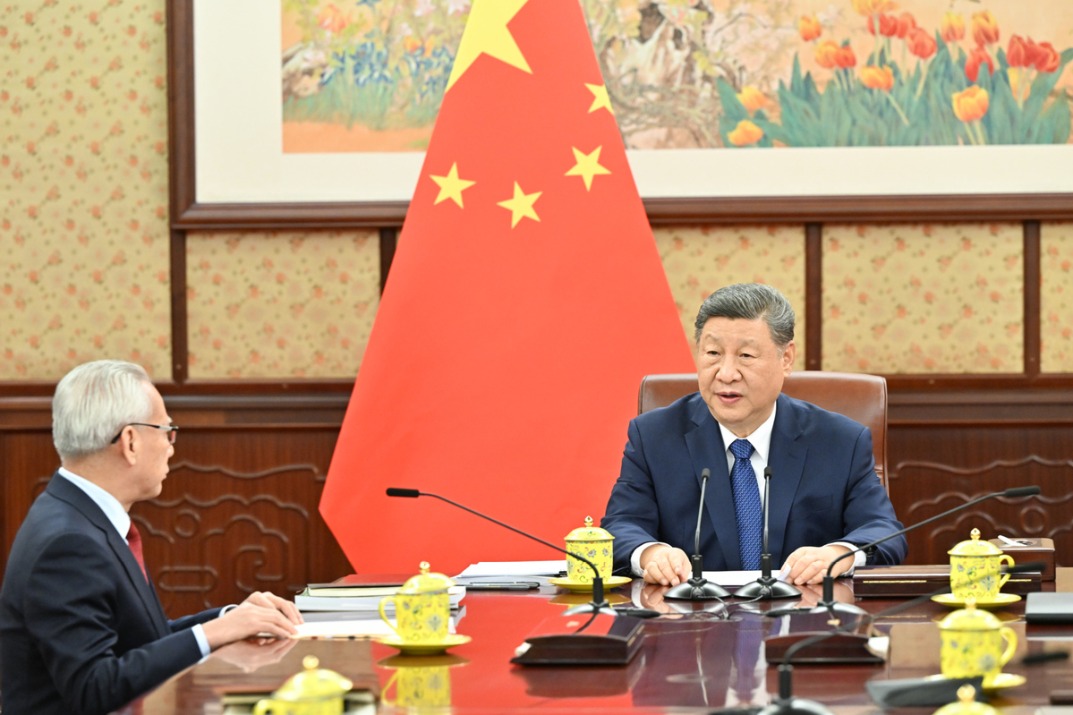

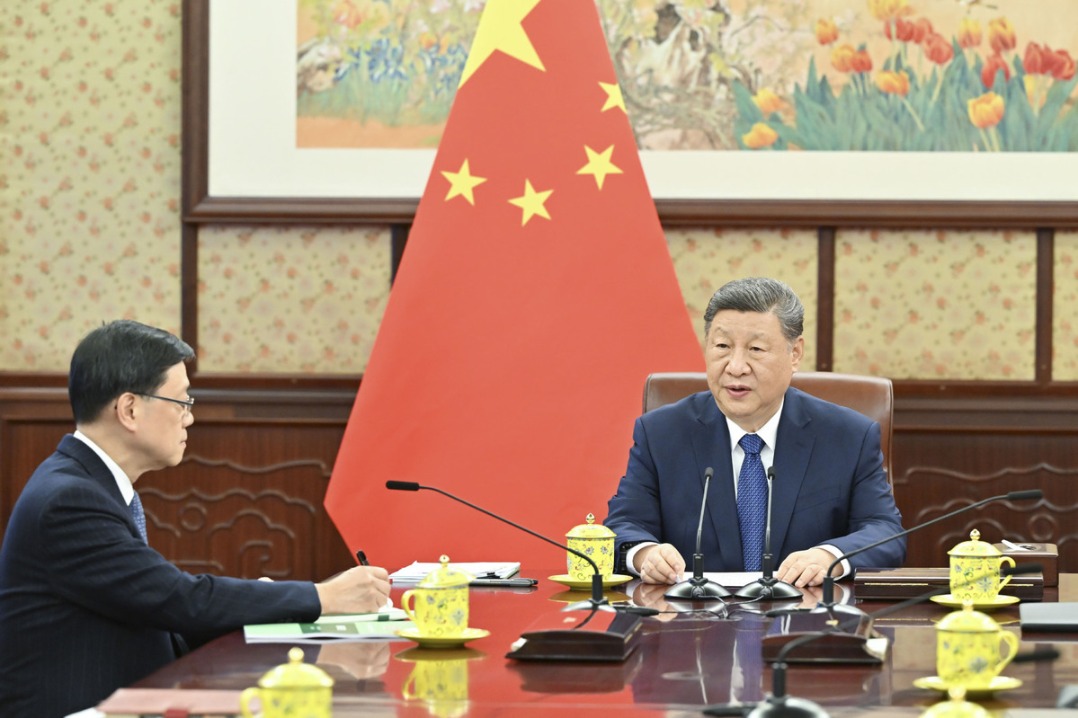

- Xi hears report from Macao SAR chief executive

- Xi hears report from HKSAR chief executive

- UN envoy calls on Japan to retract Taiwan comments