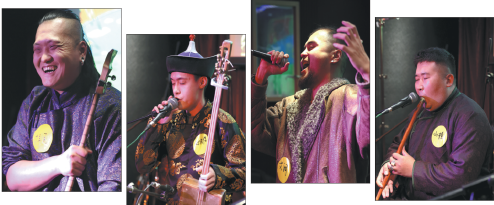

Singing the sound of nature

In China, the popularity of Mongolian vocal traditions continues to develop new depth, Chen Nan reports.

It was a Saturday night, and the air had a crisp early spring chill that seeped into the narrow passages of Beijing's hutong. A couple of young people stood outside a small bar called Jianghu. They didn't say much — just the occasional chuckle or a quick glance at their phones, their faces half-lit by the soft glow of the streetlights. The alley around them was quiet, almost reverent, as if the city itself was holding its breath.

The outside world starkly contrasted with the warmth that pulsed within the bar. As you stepped through the small wooden door, the temperature hit you, the air thick and feverish, alive with an electric charge. It was not just the heat — it was the energy that seemed to hang in the room, emerging from the deep vibrations of khoomei, an ancient art of throat singing that has traveled from distant lands to this corner of Beijing.

The khoomei tradition is found in China, Mongolia and Russia. In China, it is practiced mostly by ethnic Mongolians in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region and the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. In Russia, it is practiced by the same people in the Tuva region in southern Siberia.

The tiny bar was packed with a lively crowd, buzzing with excitement as the moment they had been waiting for approached. Cheers rippled through the air as the competition began.

But this wasn't just any kind of competition. It was a khoomei competition, and it had brought together 12 skilled performers who were expected to demonstrate their mastery of the mesmerizing vocal technique. Some had prepared songs, others would improvise, but all were ready to share their unique interpretation of this ancient tradition.

This UNESCO-recognized art is no ordinary form of singing. It's a remarkable vocal art in which the singer produces multiple pitches at once — deep, resonant tones that echo the sounds of nature, such as the wind, the rivers, the call of distant animals. It's a sound that can feel both mystical and grounded in the earth, a sound that has survived centuries of Mongolian nomadic life, carrying with it a deep spiritual connection to the land.

After the drawing of lots, the competitors took the stage one by one, beginning the first round promptly at 8 pm. There were no flashy lights, no grand set pieces — just the performers and their voices.

The first notes emerged — a low, rumbling growl that vibrated through the very walls of the bar. The crowd fell into a hush, each listener absorbed in the raw power of the sound. Murmurs of appreciation floated through the air as smartphones rose to capture the moment. The energy in the room was palpable.

Among the competitors was 27-year-old TanghisKhoo, a tall man with a quiet intensity about him. Born in Hohhot in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, he moved to Beijing with his father when he was just 3 years old. He returned to Hohhot when he was 5, and it was there that he first discovered khoomei while watching TV.

"I was mesmerized by the strange sounds," TanghisKhoo recalls. "I kept wondering, 'How can a single person produce multiple vocal tones at once?' It was both fascinating and mysterious."

A gifted musician, TanghisKhoo also plays the piano and the morin khuur (the Mongolian horsehead fiddle), but it wasn't until he graduated from high school that he decided to focus on khoomei, traveling to the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar, to study at the Mongolian National University of Arts and Culture. Last year, he graduated, and now he's on a mission to spread the art, using social media to share its magic with the world.

One of his teachers is Od Suren, a revered figure in the world of khoomei. Now in his 70s, Suren first came to China in 1993 to teach, and has since mentored over 1,000 students.

"When I first started, my throat hurt, and my voice would crack. It was incredibly difficult," Tanghis-Khoo says, his eyes reflecting the hard work behind his success. "But it was worth it. I started by listening to the masters, and when I finally produced that first sound, I knew I had touched something ancient. It was like learning a new language of sound."

TanghisKhoo now incorporates contemporary elements like jazz and electronic music into his performances, hoping to introduce a younger audience to khoomei. His work bridges the gap between ancient tradition and modern innovation, demonstrating the form's versatility and relevance today.

Another standout was 21-year-old Anha Bayier, a student at the Minzu University of China. His performance blending khoomei with urtyn duu, or long song, another traditional Mongolian vocal style known for its sweeping melodies and elaborate ornamentation, captivated the crowd. It was a blend of tradition and innovation, a seamless fusion of two art forms that both reflect vast landscapes and the nomadic way of life.

"I've been singing urtyn duu since I was a child," Anha Bayier explains, his voice filled with pride. "My family members have been urtyn duu performers for three generations. Like khoomei, it connects us to the land and to our history. Both forms present the beauty of nature, so I combined them to create something new."

Anha Bayier's fresh take on these two distinct techniques won him the competition. His mastery of khoomei and his creative use of urtyn duu may have earned him the title of champion, but it was his passion for the tradition that left the crowd in awe.

Bahajan Yells, 21, from Xinjiang's Tacheng city, won the second prize.

"While there's a deep respect for tradition, khoomei is an art form that's alive and evolving. We're always looking for new expression within the boundaries of this ancient technique," says 35-year-old Hiimorit, who was invited to comment on the performances. "I am so impressed by these young people, who preserve the art form and keep it alive with creative fusion, such as with electronic music and hip-hop."

Born and raised in the Xiliin Gol League in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, Hiimorit was introduced to music by his father, a singer. Since graduating from the Mongolian National University of Education with a doctorate in khoomei and morin khuur in 2022, he has been teaching both traditions at the Minzu University of China.

"What sets a master of khoomei apart is not just their technical ability, but the emotion they convey through the deep, resonant sounds," Hiimorit says. "The way a performer manipulates the overtones, and how they draw the audience in, is what makes a performance truly unforgettable."

He says that the appearance of khoomei in popular reality shows and movies has helped raise its profile among a wider audience. The hit animated movie Ne Zha 2, for example, features the distinctive sound, especially during mythical moments, such as the appearance of the Tianyuan Ding (a magical Taoist cauldron). Sung by Halamuji, a young Mongolian artist, it contributes significantly to the atmosphere.

"The movie's immense popularity provides a platform to introduce khoomei to a broader audience who might otherwise be unfamiliar," Hiimorit says.

A particularly exciting moment during the competition was the participation of 18-year-old Liu Haojia from Shanwei, a city in Guangdong province.

Shy and soft-spoken, the young man transformed the moment he began to sing. As soon as his deep, resonant voice filled the bar, the audience was instantly transported to the vast, boundless grasslands. They could almost feel the cool, crisp air, hear the rustling of the wind through tall trees, and sense the pulse of wild, untamed nature around them.

"I had no idea what khoomei was until I watched a performance at a restaurant in my hometown. I was instantly hooked. I had no background in anything close, so I started searching for teachers and resources," says Liu. "The sound stole my heart."

He found a teacher online. Every week, he saved up 50 yuan ($6.8) and used it to attend a 20-minute lesson with the teacher, who normally charged 200 yuan for an hour. He couldn't afford the full lesson, so he made do with what he could.

"I made lots of friends through social media who also like khoomei and sing it, which is like a bonus," says Liu, who impressed the audience and won third prize after three rounds.

"Liu Haojia's involvement in the competition is a testament to the growing popularity and appreciation of khoomei among the younger generation, even those far removed from its Mongolian roots," says the competition's organizer Liu Zhao, founder-owner of Beijing-headquartered company, Stallion Era (Beijing) Culture Communication. The company has introduced a number of artists from Mongolia and Tuva to Chinese music lovers, including Huun-Huur-Tu, a musical group from Tuva.

Today's Top News

- Experts: Lai not freedom fighter, but a pawn of the West

- Hainan evolves as gateway to global markets

- Opening up a new bridge between China and world

- Tour gives China-Arab strategic trust a boost

- China accelerates push for autonomous driving

- Opening of new gateway can help foster global economic and trade cooperation