US UNIVERSITY PRESIDENTS FACING TOUGH SCRUTINY

Resignations thrust leadership of schools into national spotlight

The resignations of the presidents of Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania in January and December, respectively, were just the start, US education experts warned.

Scrutiny and resignation pressure might take their toll on other such presidents, they said.

It didn't take long to see who might be next — Martha Pollack, president of Cornell University in upstate New York.

In a letter to the Cornell Board of Trustees on Jan 23, Jon Lindseth, trustee emeritus and major benefactor of the school, said he was withdrawing his funding.

Lindseth also called for the resignation of Pollack, accusing her of mishandling diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI, initiatives and promoting "groupthink" at the private school.

Nicolo, a freshman majoring in economics at Cornell, said the atmosphere among fellow students at the school, where about 26,000 undergraduate and postgraduate students are enrolled, is to "wait and see what the board of trustees will do".

"We just don't know," said the student from New York City, who asked that his last name not be used and declined to comment on the accusations leveled at Pollack by Lindseth.

The call for Pollack's resignation comes as leadership of US higher educational institutions was thrust into the national spotlight following the resignations last month of Claudine Gay at Harvard and Liz Magill at the University of Pennsylvania in December.

With these resignations, the issues of plagiarism and antisemitism — along with the influence of wealthy donors — moved into the spotlight on college campuses and in the offices of those who lead them.

Gay, a political scientist, became Harvard's first black president and also president of the oldest US college with the shortest tenure — of just over six months.

The two resignations raised numerous questions, including what the increasingly polarizing political climate in the US might mean for higher education — especially amid the 2024 presidential election campaigns. There is also the issue of the right to free speech and whether the swirling controversy and problems entangling US higher education might reduce interest in becoming a university president.

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, or ACE, and a former president of Occidental College in Los Angeles, told The Washington Post, "There's no question that people are thinking twice now about whether they want to be college presidents.

"It has always been a 24/7 job. There have always been multiple constituencies, but what seems to have happened over the last few years is that the volume dial for all of those constituencies has turned up."

Jonathan Fansmith, senior vice-president of government relations at ACE, which represents colleges and universities, said he had anticipated a heightened attack on higher education.

"Everyone expects in 2024, especially given the election cycle, you're going to hear a lot of pretty heated rhetoric and you're going to see a lot of people who, for whatever electoral reasons, want to hold up colleges and universities for attack," he told GBH media.

Cancel culture

Fansmith's comments were echoed by Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, an organization whose advocacy focuses on college campuses and has challenged the suppression of free speech by people of varying political beliefs.

"I wouldn't exactly envy university presidents in the current environment," he said. Lukianoff anticipates a particularly tumultuous time for leaders who have espoused progressive ideals. "We are likely going to see an uptick in cancel culture coming from the right," he told USA Today.

The resignations of Gay and Magill come as higher education institutions face numerous challenges, including the high cost of attending schools, the value of higher education, the shrinking number of students, and the growing politicization of higher education.

Doug Shapiro, executive director of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, said that compared with a decade ago, there are now 2.5 million fewer students enrolled in college in the US.

There always has been a divide between Republicans and Democrats — and higher education, but education experts say it has now deepened, and recent polling illustrates this.

In 2015, polling by Gallup found 56 percent of Republicans had "a great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in higher education. By 2023, the proportion had fallen to 19 percent. Confidence fell among Democrats, too, but far less dramatically, from 68 percent to 59 percent.

Reports of antisemitism and tension on college campuses related to the Israel-Hamas conflict have been a topic of heated discussion and threats, including some violent clashes amid demonstrations. Students on both sides have raised concerns about their safety as tensions remain high.

Antisemitism has increased on several campuses, including Cornell. Israel's offensive in Gaza also triggered a wave of pro-Palestinian protests on campuses and elsewhere in the US.

College administrators are grappling with how to keep campuses secure and denounce the violence in the Middle East without wading too deeply into the supercharged political and historical dispute.

But many of them have been widely criticized for their responses to Jewish students' complaints of antisemitic incidents and hostility toward them on campuses.

Questions asked

Fallout from a Congressional hearing on Dec 5 that led to the resignations of Gay and Magill continues to reverberate.

Republican New York Representative Elise Stefanik questioned Gay, Magill and Massachusetts Institute of Technology President Sally Kornbluth during the hearing about incidents of antisemitic harassment on their campuses.

Stefanik asked each of them whether anti-Israel students calling for the genocide of Jews in the wake of Hamas' attack on Oct 7 violated their universities' codes of conduct related to bullying and harassment.

Gay and the others declined to give a yes-or-no answer, emphasizing that this would depend on "context" and only warrant action if such actions rose to the level of bullying, harassment and intimidation.

Their answers infuriated Stefanik, who is a Harvard graduate, and also brought strong criticism from political leaders in both parties, a White House spokesman, as well as Jewish community advocates, alumni and donors.

Doug Emhoff, the husband of US Vice-President Kamala Harris, denounced the university leaders.

"Seeing the presidents of some of our most elite universities literally unable to denounce calling for the genocide of Jews as antisemitic — that lack of moral clarity is simply unacceptable," said Emhoff, who is Jewish.

High-profile critics of the three university presidents include hedge fund billionaire and Harvard alumnus Bill Ackman, who has donated more than $25 million to the university and called repeatedly for the three to resign.

Gay resigned on Jan 2 after the backlash from her congressional testimony, allegations of plagiarism emerged, and doubts arose about her academic integrity. Her tenure of just six months and two days is the shortest in Harvard's history.

Magill stepped down the month before. Kornbluth has received strong endorsement from MIT's governing board and remains in office.

Following the hearing and resignations of the two presidents, Stefanik issued a warning on what lies ahead. "This is just the beginning of exposing the rot in our most prestigious higher education institutions," she said.

House Republicans are continuing a broader investigation into what Stefanik called "a fundamentally broken and corrupt higher education system," including antisemitism on campus and DEI initiatives.

As for the flap at Cornell, scrutiny of DEI initiatives isn't new. Conservative lawmakers have for years claimed DEI efforts are a form of indoctrination.

Last year, more than a dozen state legislatures introduced or passed bills reining in DEI programs at colleges and universities, claiming the offices overseeing them eat up valuable financial resources, The Chronicle of Higher Education reported.

Many DEI initiatives have been credited as beneficial, as they are seen as a way to combat inequality by encouraging multiculturalism and providing resources for people of different backgrounds.

ACE surveys college presidents about their jobs. Each of its previous three such studies has shown a decline in length of service.

In its survey released this year, more than 1,000 presidents and chancellors from a broad range of institutions told ACE they had worked in their positions for an average of 5.9 years. Previous surveys found an average of 6.5 years in 2016, seven years in 2011 and 8.5 years in 2006.

Some education experts are worried about what this turnover means for institutional stability.

"I think institutions, whether they're journalism institutions, business institutions or higher education institutions, benefit from stability and continuity that comes from long-term relationships with leadership. And if there's excessive turnover, I think the institution suffers," said Robert Dickeson, a higher education consultant and former president of the University of Northern Colorado.

Dickeson, who served as president for a decade, told Inside Higher Ed, a print and digital media outlet owned by Times Higher Education in the US, that presidents have to "hit the ground running", which he believes makes it difficult to do the job.

"Leaders often need at least a year or two to get their bearings and figure out the institution's inner workings. At the same time, if they stay too long, it can mean that the university stagnates due to a lack of fresh ideas from the top," he wrote.

He believes the ideal tenure for a university presidency is between seven and 10 years.

Dickeson, who recently wrote a guide on the presidential search, screening and selection process for the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, said boards have to take responsibility for failed presidencies, given their role in finding and hiring college leaders.

"If I was on the board, I would say, 'OK, what went wrong? How did we screw up?' Because the fact that the person has left is as much our fault as theirs, if there is fault to be assigned," he said.

Holden Thorp, a former chancellor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, wrote in an article for The Chronicle of Higher Education last month that today's college presidents need to be prepared right from the start "to go toe-to-toe with seasoned politicians in high-stakes public hearings. When world events strain the campus, they (college presidents) also need the experience and judgment to not send out statements except in cases where they're supposed to send one out."

Zachary Smith, executive partner in the education practice of WittKieffer, an executive search company, said candidates are opting out of some presidential searches because of the political environment.

"People are taking a little bit longer look at whether they want to jump into the furnace and operate in environments that are not necessarily conducive for their success or their institution's success," Smith told The Washington Post.

Roderick McDavis, the first black president of Ohio University, who is now a managing principal and chief executive of AGB Search, said that while there are still plenty of people who want the jobs, he thinks tenures are shorter because the role is so much more stressful.

He told the news website Axios that when he was president of Ohio University from 2004 to 2017, it was a rewarding job, but it became increasingly all-consuming. "There's literally never any downtime," he said.

David Gearhart, chancellor emeritus of the University of Arkansas, who has written books on higher education leadership, told Inside Higher Ed that a college presidency has become an increasingly hard job due to challenges that only seem to be increasing.

"There are so many groups out there that a college president has to try to appease, and it's almost impossible to do that with all of the political machinations that are happening these days, not to mention the huge decline that we will be seeing over the next several years in enrollment, which has already started," Gearhart said.

Steven Mintz, a professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, said political attacks on US higher education are not new.

But the biggest threat, Mintz wrote in Inside Higher Ed, "comes from mounting anxieties about colleges' return on investment: that the cost of attendance is too high, completion rates are too low, and learning and employment outcomes too uncertain, and that society needs to embrace faster, cheaper and less rigorous and well-rounded paths into the workforce."

He fears that "the true political threat to universities comes less from ideologues than from a diminishing faith among broad segments of the public in the power of higher education to transform lives, open doors and open minds".

"It's that loss of faith that gives traction to the recent political attacks," he added.

Today's Top News

- Foreign ministers of China, Egypt call for Gaza progress

- Shield machine achieves Yangtze tunnel milestone

- Expanding domestic demand a strategic move to sustain high-quality development

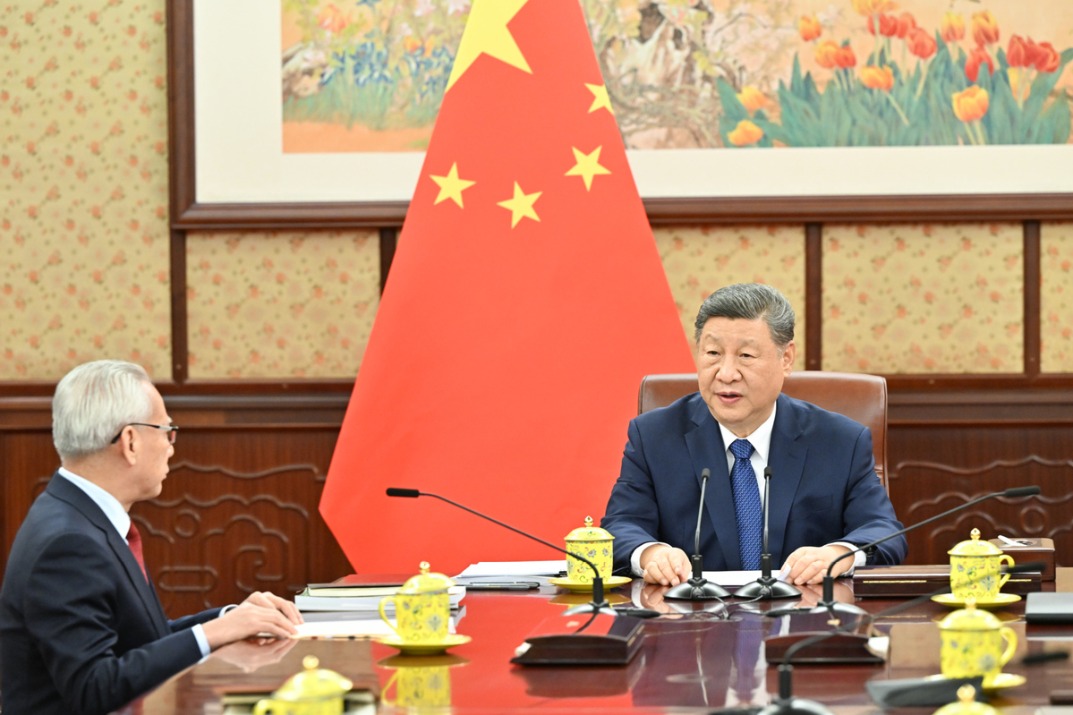

- Xi hears report from Macao SAR chief executive

- Xi hears report from HKSAR chief executive

- UN envoy calls on Japan to retract Taiwan comments