The keeper of social conscience

One of the early Chinese practitioners of performance-based art intervention, Lin Yilin continues to critique societal inequities. The Guangzhou-native who now lives in New York City reacts to rising incidents of Asian hate with a series of videos, sculptures and installations. Charlotte Yu reports.

Lin Yilin, a leading Chinese artist in the field of performance-based art intervention, emerged in the early 1990s. He was first noticed for putting on shows on the streets of his native city of Guangzhou, which served as both location and subject. Since then, Lin has performed in Hong Kong, Rome and San Francisco, and exhibited his works in high-profile venues around the world, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York City and Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland.

Hong Kong's M+ museum has a number of works by the artist in its collection. Highlights include Typhoon, a video of a performance piece, which was part of the museum's Sigg Prize 2019 Exhibition. In it, Lin is seen walking on stilts down a deserted Guangzhou street in the dead of night. The street's 19th-century colonnaded pavements seem haunted by a sense of dereliction. The scene represents the gradual disappearance of heritage as a result of urban development - a recurrent theme in the artist's works.

In March, Lin made an appearance at Art Basel Hong Kong, speaking at a panel to mark the launch of Interventions in the Greater Bay: Reconstructing the Archives of Big Tail Elephant Group, a book celebrating the artists' collective Lin had co-founded with fellow artists Liang Juhui, Chen Shao- xiong and Xu Tan in 1990.

The Big Tail Elephant Group was around for 15 years, mainly calling attention to the rapid urbanization of Guangzhou through their creations, and continues to be regarded as a milestone in the history of Chinese contemporary art for its vision and vitality.

Live art pioneer

When Lin began his artistic journey, in the early '90s, the concept of live art was relatively new in China.

One of his early major projects is called Safely Maneuvering Across Linhe Road (1995). In this performance piece, Lin moves a wall, tile by tile, across a road in Guangzhou's central business district. The idea is to disrupt the usual flow of traffic on a busy road.

One of the reasons why Lin, and his Big Tail Elephant mates, began putting on shows in public spaces was "because there weren't enough indoor spaces". The group held five exhibitions at unconventional venues, including a community center and a bar, from 1991 to 1996.

The group's 1998 show at the Kunsthalle Bern was curated by Bernhard Fibicher. He believes that Big Tail Elephants' experiments with art in the '90s were aimed at blurring the distinction between public and private spaces. Lin's Safely Maneuvering piece, Fibicher suggests, is the artist's response to the culture shock suffered in the wake of China's reform and opening-up.

The journey continues

As part of 2011's Imagery Knowledge Science, Lin led a crowd to an alley in Vancouver's Chinatown. It used to be a particularly run-down neighborhood - with tons of homeless people, including drug addicts, hanging out in its lanes - and had been chosen for a major development since.

Once there, Lin began pasting "wanted" posters with images of North American prisoners on telephone poles and announced details about how to identify them. Next, he climbed up a ladder to insert a small photo inside a crack on one of the poles, drawing a pair of eyes on it.

Stacy Ho, an artist who participated in that site-specific performance, says that it felt likebeing party to the gentrification taking place in a neighborhood that was changing fast. "No matter how mindful or respectful our intentions, the sheer size of the group following the artist was forcing everyone else present on the scene to move aside." Ho describes Lin's piece as a "harsh but considered contribution" to the broad-based dialogue about an artist's role in society.

Addressing Asian hate

Lin moved base to New York in 2001 but his ties with his home country remain strong. In recent years he has turned his attention to the rise of racial prejudice, particularly against Asians, in the West, responding to such incidents through his art.

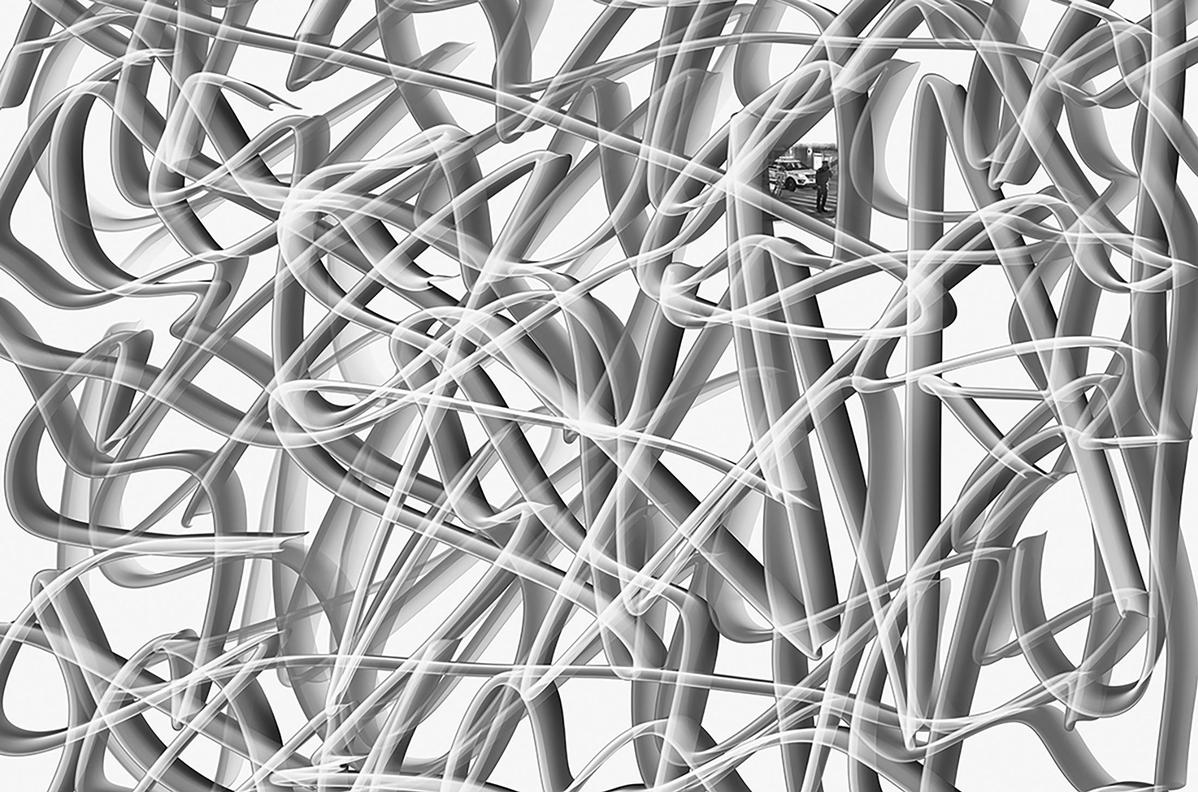

In 2022, SPURS Gallery in Beijing hosted NOHATRED, a solo show of recent works by Lin. A highlight piece in that exhibition is called Real News (2021). In it, the photo ofa Chinese person under attack in New York is almost invisible under a much-larger and intense maze of black-and-white, digitally produced squiggles.

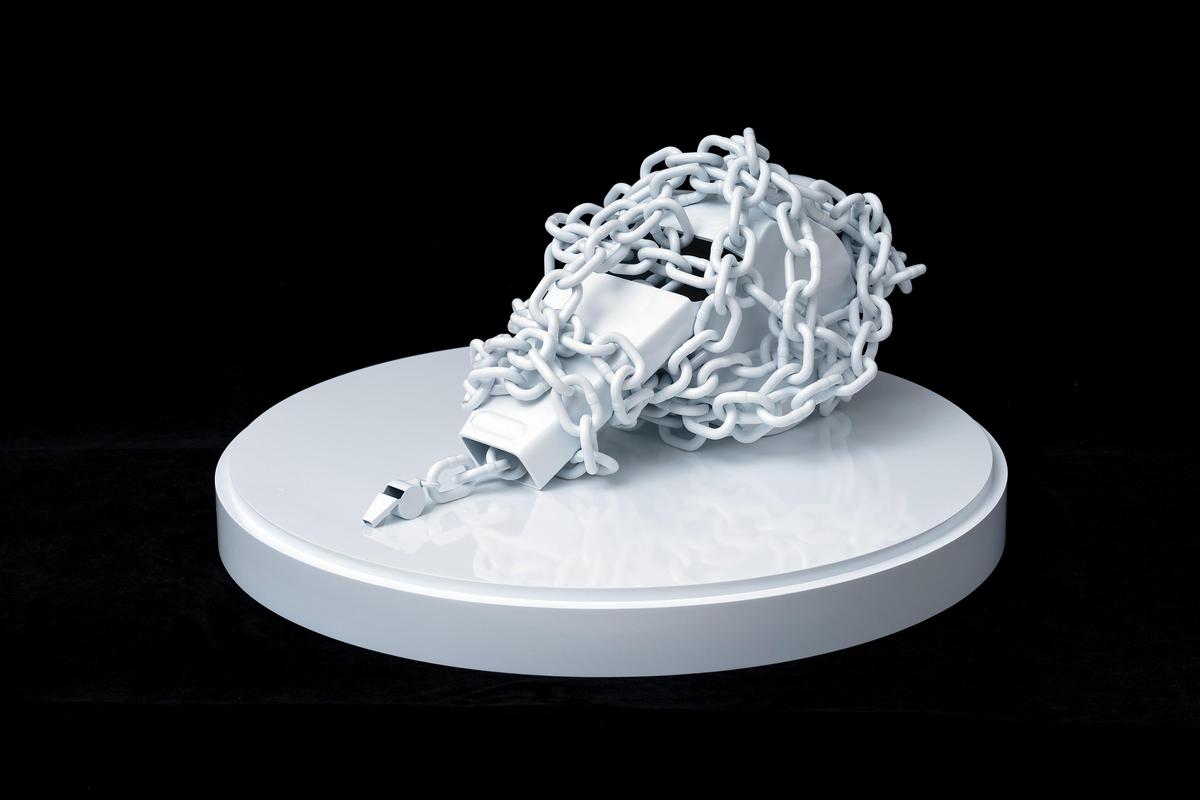

The show also included sculptures made out of resin - an enormous whistle bound up in chains, for example. It's the artist's way of symbolically gagging the noises made by tyrannical law-enforcement personnel (think George Floyd, who was suffocated by a Minneapolis police officer pressing down his knee on the victim's neck in May 2020).

According to the Department of Justice of the United States, in 2020, anti-Asian crime soared by 77 percent. A total of 279 cases were reported. As groups of minority communities took to the streets to protest against racism, the mainstream media looked the other way.

"The mass protests in Manhattan, urging people to 'Stop Asian Hate', didn't get a page in mainstream outlets," Lin recalls. His own response to what he believes was a case of studied silence was to make a four-channel video called Non-news (2021). It shows two protests led by tens of thousands of Chinese people denouncing anti-Asian hate,and two more asking for the elimination of the Specialized High School Admissions Test, which supposedly has a history of favoring affluent white candidates.

Non-News was preceded by 20200313 (2020), a black-and-white video showing people's reactions to a key moment in American history. On that date - March 13, 2020 - then-US president Donald Trump declared a national emergency on account of the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the most striking images on that video is a close-up of the artist's face, turned upside down and wearing a surgical mask. His eyes express fear, grief and disbelief - being witnesses to the spiral of chaos and deaths, unleashed by the pandemic, as well as deep-rooted systemic failures entrenched in society.

His increasing preference for neutral shades might be read as a response to New York City Mayor Eric Adams' remark against Andrew Yang when both were running for the city's top job in 2021. Adams had said that Yang and his supporters couldn't "trust a person of color to be the mayor", ignoring the fact that the Chinese American Yang was not white either. Lin, who was deeply affected by the incident, reacted by making a two-channel video titled Un-colored.

While such an interpretation may or may not be accurate, it is evident that the artist no longer considers public spaces as his only platform. Lin seems to have turned over a new leaf in his artistic career. Nowadays he is as much at ease marrying physical action with digital technology and exhibiting his artworks in galleries.