LEARNING TO PAINT: A FAMILY AFFAIR

For members of elite households, painting was a shared language, Zhao Xu reports.

If you are a friend of a powerful art family and own a painting by its patriarch, what would you do? The answer from Xie Boli, a collector living in 14th-century China, produced one of the most prominent and talked-about works in Chinese art history.

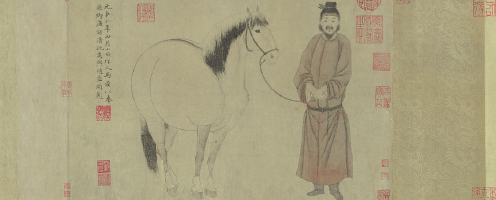

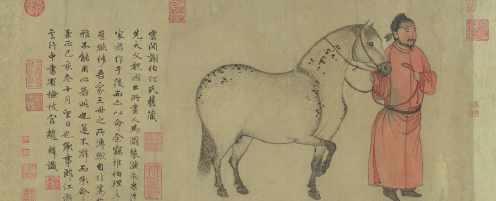

The original piece that was in Xie's possession was Groom and Horse by Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), a crucial figure in the evolution of China's literati painting tradition. Exactly how and when Xie came to own this masterpiece remains unknown to modern-day art historians. But what they do know, from the inscriptions on the complete piece as we see it today, is that the collector approached Zhao Yong, the master's son, in the autumn of 1359 and then his grandson Zhao Lin barely two months later.

On both occasions, Xie asked if another picture of the same theme could be added to the existing one, and his wish was granted both times, resulting in a paint scroll that features, in succession, three pairs of horse and groom, as rendered by three generations of the Zhao family.

The piece kept growing in the ensuing centuries, with nine people who had come into its audience putting down their thoughts in colophons that are attached to it. The last one of them is poet and figure painter Chen Hongshou (1598-1652).

"Instead of mere ink-and-brush skills, the most precious thing that could be transmitted from one man to his posterity is the moral value and the literary tradition in which it is embedded," Chen wrote, probably thinking about himself and his son Chen Zi, who had inherited in his own art the old man's style but not his signature "quirky charm", to use the words of Joseph Scheier-Dolberg, the man behind the ongoing exhibition Learning to Paint in Premodern China at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The curator has put on display both the Zhao family painting and an album featuring four painted leaves from Chen Hongshou and seven from his son — they are believed to have been brought together either by a collector or by the son himself.

"There could be no greater advantage than to be born into an artistic family," Scheier-Dolberg reflects.

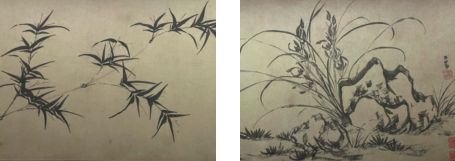

This is especially true for Zhao Yong and Zhao Lin, whose mother/grandmother Guan Daosheng (1262-1319) was artistically on a par with her husband. For proof, one only needs to check out the scroll displayed right beside the horses-and-grooms one. Here, Guan's bamboo, for which she was famous for, was served up in the form of what appears to be a little more than a sprig. Yet the painter played on the contrast between the extremely slim, barely-there stems and the strung-together leaves rendered emphatically in dark ink, producing an effect that's both vigorous and graceful.

Entering the picture from the left, Guan's bamboo was greeted by the slender, elongated leaves of the orchid flowers painted by her husband that occupy the right part of the scroll. The reciprocity was so obvious that they seemed to have been painted on the same piece of paper — except that they were not, judging by a seam in the middle.

"Whether they were intended to go on the same handscroll at the moment they were painted, we don't know. But by the mid-14th century, they were already joined together to give generations of art lovers something to celebrate," says Scheier-Dolberg.

The couple were as much bonded by the vagary of times as by their shared artistic language: in 1279, the Song Dynasty came to an end, succeeded by the empire of Yuan founded by the Mongols. In around 1286, Guan, who's "probably the highest-regarded woman painter-calligrapher from Chinese history" according to Scheier-Dolberg, traveled with Zhao Mengfu to Beijing to serve the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) government of Kublai Khan, a highly controversial decision among their contemporaries given Zhao's background as a direct descendant of the Song royal family.

Thanks to the fame she was able to gain even before her marriage, Guan's arrival in the Yuan capital "was recognized by the larger community", says Scheier-Dolberg. But it was what Zhao Mengfu was able to achieve there, as a much emulated scholar-official powerful enough to hoist literati painting onto the pedestal of Chinese art, that had come to have a profound impact on those who came after him.

Among them was his grandson Wang Meng (1308-85), featured in the same gallery with his grandparents, his maternal uncle (Zhao Yong) and his cousin (Zhao Lin). Posthumously, Wang was to share the lustrous designation of "the Four (Painting) Masters of the Yuan Dynasty" with three others including Huang Gongwang (1269-1354), whom Zhao Mengfu also tutored.

Reflecting on the height the Chinese literati painting had reached during the Yuan Dynasty, Wang Yimin, an ancient painting-and-calligraphy expert from the Palace Museum in Beijing, says: "The development of art followed its own curve. For literati painting, the idea first germinated during the Tang Dynasty between the seventh and eighth century, when poet-painters started to see painting as being fueled by whatever was driving their poetic creations.

"During the ensuing Song Dynasty (960-1279) — a golden period of Chinese literature, painting was approached as a form of personal erudition and expression by men of words, many of whom were rather shaky on the technical side of things," Wang Yimin continues. "All this had paved the way for the Yuan Dynasty painters, who made big progress in combining solid training with sensibilities in line with their literary tendencies."

Meanwhile, the attitude of the Mongol rulers toward what they had inherited also played a big role, according to Wang Yimin. "Following the fall of Song, Kublai Khan had scouts out and about searching for prominent intellectuals who could possibly serve his court — that's how Zhao Mengfu was brought to his attention," he says. "Jayaatu Khan, the eighth emperor of the Yuan Dynasty, was so eager to be seen as a true guardian of the country's art legacy that he enlisted the help of a scholar-painter named Ke Jiusi, whose connoisseurship he relied on to sort through the massive art collection put together by successive Song emperors."

And Ke was among those who paid their due tribute to this Guan-Zhao union on paper. This was done through writing colophons which collectively offered glimpses into the dense web of friendship and family connections that were often central to the process of art learning in ancient China.

Yet one aspect of this process — and perhaps the least openly-discussed aspect — is that despite all the privileges, few born into a luminous art family grew up to outshine their ancestors. That's because "when one was kept from an early age within the shadow — or aura — of his father and grandfather, who were most likely in control of every aspect of his art education, it would be very hard for the person, humbled and in reverence of the family legacy, to really outgrow that experience to form something uniquely his own," says Wang Yimin. "And to have something of his own was the only way one could possibly carve out a place right beside those he once looked up to."

One man whose life could have followed the storyline of an elite family-trained scholar-artist struggling to find his own voice was Zhu Ruoji (1642-1707), who had the good luck to be born into the royal family of the Ming Empire (1368-1644) and bad one to have this happen two years before its collapse. Finding shelter in a Buddhist temple following the killing of his father when he was mere 2, Zhu, who later adopted the art name Shitao (meaning stone wave), was denied at a young age nearly all access to old-master collections a privileged art education would certainly entail.

Instead, the man he grew up to be cast his eye on nature, following her lead "in search of every mountain peak amazing enough to be put into my sketchbook", to quote Zhu himself. Thanks to that approach, Zhu created some of the most breathtaking pieces known to the Chinese art history, with an intuitive, almost willful style that never failed to respond to either nature's changing moods or his own temperaments. The result is transcendental rather than simply representational.

However, his idiosyncratic approach didn't mean that he was not conscious of what had been done by those who came before him. Although he was never quite able to find ease with the art-world establishment of his time, he did share their view that history offered lessons and that anyone in search of the true spirit of Chinese painting should look beyond the recent past into the more distant one.

"Paintings done during the beginning and the middle part of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) are infused with a powerful magnificence," he said, before going on to lament on its loss in the following centuries.

Zhao Mengfu probably would have agreed. "Instead of going to the stables to look at horses, Zhao and his son and grandson were thinking about old horse-paintings from the Tang Dynasty which, thanks to the flourishing Silk Road trade, was seeing a steady arrival of sturdy steeds from Central Asia," says Scheier-Dolberg. "That explains the grooms' big bears and distinct facial features."

With what a later colophon-writer described as "manes like dark jade" and "four snowy hoofs" that had allowed it to travel the long distance to be "paraded in the emperor's stable", Zhao Mengfu's horse is a symbol of art-historicism. But more than that, in an ancient China where little possibility for personal advancement existed outside of the world of officialdom, the horses — "extraordinary creatures with leisurely manners" to quote from the same colophon — conveyed an urgent longing of the society's educated members. They, too, wanted to be in "the emperor's stable".

"To avail oneself of the chance to serve the emperor and by extension the populace under his rule, that was considered noble. And that might explain Zhao Mengfu's thinking behind his active participation in the Yuan government," says Wang Yimin.

As in art-making, his son and grandson and nephew followed his footsteps, to different ends. Approaching his 50th year, Zhao Lin, the grandson, was able to find favor with the founding emperor of Ming Dynasty. His cousin Wang Meng, on the other hand, was not as lucky: serving the same Ming emperor, he found himself embroiled in a political struggle that cost his life. He died in prison in 1385.

In 1359, 37 years after the death of Zhao Mengfu, Zhao Yong was brought face to face with his father's horse-and-groom painting, done when he was 7 and just starting to learn his art.

Asked to add a sequel and inscribe it, which Zhao Yong did later the same year — and some believe one year before his own passing — the son was emotionally overwhelmed by his encounter with this long-lost piece of memory.

"I was overpowered by a mixture of joy and sorrow, and simply couldn't put the painting down," he wrote.

Today's Top News

- Effective use of investment emphasized

- China's shuttle diplomacy strives to reach ceasefire

- Nanjing Museum's handling of donated art, relics being probed

- Key role of central SOEs emphasized

- New travel program hailed as 'milestone'

- Animated films top draw at box office