When LA's wounds left a nation scarred

30 years on from Rodney King, calls for racial justice in US remain as urgent as ever

Editor's note: This is the first of a three-part series on race issues in the US. From the Tulsa massacre in 1902 to the death of Vincent Chin in 1982, to the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in 2020, and the recent mass shooting in Buffalo, New York, racial minorities have long been victims of hate crimes.

The tension in the air was almost palpable as Jackie Ryan drove home from work on April 29, 1992. Earlier that day, a jury had acquitted four white police officers accused of beating black motorist Rodney King. As she rounded a corner, the now-retired shop owner spotted people on trucks carrying flags.

"And I'm going, this is something really real here. People are angry," Ryan, 85, a longtime resident of South Los Angeles, where the LA riots sprang up, told China Daily.

Since the Rodney King incident, the United States has gone on to witness yet more police violence against black people. High-profile cases included the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014, the death of Freddie Gray in 2015, and more recently, the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd in 2020. The second anniversary of Floyd's murder is Wednesday.

For more than a year, people watched an amateur videotape on television showing a group of police officers repeatedly striking King after a high-speed chase. The officers reportedly struck King 56 times with their batons while he lay face down. The verdict shocked and devastated the community, Ryan said.

Increasing the tension was the fatal shooting of black teenager Latasha Harlins by a Korean-American grocer who accused her of stealing orange juice. The grocer, convicted of voluntary manslaughter, got probation, which a state appeals court upheld just a week before the King verdict. The court's decision was considered a light punishment by many in the black community, she said.

Ryan watched flames engulf shops in the neighborhood as news of the verdict on King's case spread. The blaze scorched a grocery store and was edging closer to a business across the street from her African cultural store, so she raced to help her friend move things from his building.

That night, Ryan and fellow store owners slept on the sidewalk to guard shops against arson by the rioters. Meanwhile, several blocks away at First African Methodist Episcopal Church, the city's oldest black church, pastor Najuma Smith-Pollard was in disbelief over the verdict.

"It was devastating; it was very hurtful," she told China Daily. So many pastors, civic leaders, officials, media and community members had congregated at the church that day for service and mediation under the guidance of the church's senior pastor, Cecil L. Murray, that it was "beyond standing room only", Smith-Pollard said.

When the then 20-year-old went home that night, a trip that took Smith-Pollard across South LA, she experienced firsthand the "complete mayhem" left by the racially fueled explosion.

"It wasn't that I was afraid of the people, I was just afraid of like, how does our city recover, where do we go from here," said Smith-Pollard, who serves as the assistant director of community and public engagement at the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

Following the initial uproar on April 29, the city plunged into five days of looting, assault, arson and murder in one of the worst episodes of civil unrest in US history.

Most of the violence was concentrated in South LA, a predominantly black and Hispanic neighborhood, as well as Koreatown, where resentment had grown between Korean and African Americans. In all, more than 60 people died, most were black and brown, thousands were injured and nearly $1 billion in property was damaged, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Critics blamed the city's lack of a detailed plan for the crisis and the police department's slow response to stopping the violence that spread throughout the city. Some witnesses also accused the police of leaving the poor communities of color to fend for themselves while directing armed personnel to affluent areas like Beverly Hills.

The unrest spotlighted for the world the racial and economic inequality that existed in one of the most diverse cities in the US. This year, Los Angeles marks the 30th anniversary of the riots with a series of commemorations, celebrations and peace gatherings. Those who lived through the violent days, however, said the struggle with racial injustice continues despite some progress.

King, who died in 2012 aged 47, wasn't the first black man, or the last, to be beaten by police, Smith-Pollard said. But it was the first time it was caught on camera and shown to the world.

'Too disrespectful'

"For people to see that it was like, 'Oh my God, we finally got footage' because this happens all the time," she said. "So now, we are not just mad about Rodney King; people are mad about every other black and Latino man who had a Rodney King experience, and nobody knew about it, and nobody could do anything about it."

That's why the ensuing verdict was so painful because people couldn't believe that even with sound and images, nothing changes, "that is just too disrespectful", she said.

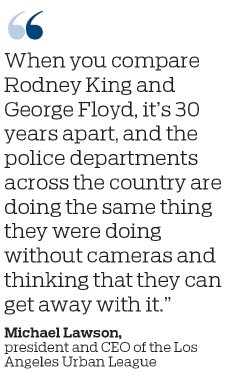

"A slap to the face" was too soft a term to describe how his community had felt in the wake of the acquittal of the officers and the Korean grocer, Michael Lawson, president and CEO of the Los Angeles Urban League, told China Daily. His organization is dedicated to helping African Americans and others in underserved communities.

"We were skeptical but hopeful at the same time; that verdict dashed our hopes," said Lawson, who was listening to the radio in his car when the jury's verdicts came 30 years ago.

"When you compare Rodney King and George Floyd, it's 30 years apart, and the police departments across the country are doing the same thing they were doing without cameras and thinking that they can get away with it," Lawson said. The difference with Floyd's murder is that it resulted in a conviction, in 2021, he added.

Floyd died on May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis after Derek Chauvin, a white police officer, knelt on the black man's neck for more than nine minutes while Floyd was handcuffed and pinned to the ground. His death, which a bystander captured on her cellphone, sparked protests around the world against racial injustice. Still, the black community waited with great concern for Chauvin's sentencing because police are rarely held accountable in the US, Lawson said.

"Those of us who are old enough to remember held our breath, when the murderer of George Floyd was sentenced because we knew that time after time after time, the officers get acquitted, and finally, we have a situation where the officer was convicted," he said.

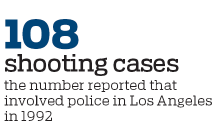

The Los Angeles Police Department had 37 instances of shootings by police in 2021, compared with 108 in 1992. Thirty years ago, 60 percent of the officers were white. Last year, white officers made up 28 percent of the force; Hispanics, 52 percent; Asians and Pacific Islanders, 11 percent; and blacks, 9 percent, according to the department's year-end review.

Lawson acknowledged that progress has been made in relations between communities of color and law enforcement over the years, but "there's a lot of work to be done. It's not just LA, it's across the country now," he said.

Gina Fields was a college student studying at the University of California in Berkeley when the riots broke out in 1992, but the tension in Los Angeles during the months leading up to it was not lost on her.

"There was a lot of anger in the community, and people didn't really have a place to put that anger," said Fields, who grew up in South LA and now heads the Empowerment Congress West Area Neighborhood Development Council.

Many African Americans were being pushed out of South LA by the influx of immigrants from South Korea, Mexico and Central America. The black neighborhoods in the city continued to shrink, while Korea-town and other ethnic communities expanded, she said.

"Prices were rising, rents were going up and the money people were making wasn't increasing," Fields told China Daily.

African Americans also faced hurdles in getting business loans. They were instead given to Korean Americans who opened liquor stores in black neighborhoods, she said.

High unemployment

Brenda Stevenson, an Oxford University history professor, told China Daily that swathes of the neighborhood were plagued by high unemployment. Residents also had trouble getting affordable housing and adequate education and health resources. That, along with the high incarceration rate of African Americans and Hispanics, contributed to the unrest, she said.

The socioeconomic injustice that existed in 1992 is still present today, she said. In addition, the homeless population, made up mostly of brown and black people, has grown tremendously. The underlying racial disparities were further exposed during COVID-19, when ethnic minorities had limited access to treatment and testing, she said.

"There are so many things that are going on today that are both similar to and in some cases worse than it was in 1992," Stevenson said.

Between 1960 and 2016, in metrics such as income, housing, transportation and education, residents in South LA still lagged far behind others in Los Angeles County, according to a study by researchers from UCLA called "South LA since the Sixties". In 2016, a full-time employee in South LA made an average of 60 cents for every dollar earned by a county resident.

Many vacant lots where the riots occurred remain undeveloped. Large store chains don't want to come to the area for fear of another civil unrest, Fields said. "Fighting for our rights still doesn't necessarily get us what we need in our community," she said.

Although racial relations between minority groups have improved, Los Angeles remains a segregated city.

"Here in LA, you have one ethnicity living in Santa Monica on the West Side; you have another living in the Wilshire area; you have another living in South LA; you have another living in East LA," Fields said.

Los Angeles is a sprawling and car-driven city. Unlike other large cities such as New York or Chicago, where people usually take public transportation, residents here get into their cars and arrive at their destinations without encountering anyone else, Lawson said.

"We are so segregated that you can literally live your life not interacting with people of another ethnicity if you don't want to," Fields said.

A lot of the people in these ethnic communities speak only their native tongue, she said. The isolation between the ethnic groups resulted in language and cultural barriers, which contributed to the tensions and probably led to the misunderstanding between Harlins and the Korean grocer, Fields said.

"I think in the immediacy of the moment that different ethnicities may have felt that we were fighting against each other, but I think over time, what we've learned to understand is we are just all fighting to be treated fairly," Fields said.

Both the Korean and the black communities have realized that they have more similarities than differences.

About half of the damage from the riots was sustained by Korean businesses. Many store owners felt that they had been abandoned by law enforcement when police protection didn't show up.

Connie Chung Joe, chief executive of Asian Americans Advancing Justice-LA, was in high school during the riots. She recalled hearing about friends' parents and her own relatives going to rooftops with guns to protect their businesses from potential looters.

"For Korean Americans in LA, it's one of those moments we never forget, much like 9/11 was for all Americans," she told China Daily.

Joe noted that two racial movements, Stop Asian Hate and Black Lives Matter, have been pushed to the forefront during the pandemic. She urged members of ethnic groups to reach across racial lines to establish solidarity.

"I think what needs to be done to address racial disparities is to really think about how communities of color must work together to fight racial oppression instead of allowing ourselves to be pitted against one another for scraps of attention and resources," Joe said.

More work needs to be done to resolve "long-term racial tensions", she said, noting the belief that anti-Asian hate crimes in recent years have been committed by African Americans is "factually incorrect".

Marsha Mitchell, communications director at Community Coalition, a South LA-based organization working to enhance the area's conditions, echoed that comment.

"There is a current narrative trying to pit black and AAPI communities against each other. But the attacks and targeting of AAPI people are squarely rooted in white supremacy, which is embedded in American racism," she told China Daily.

Fair treatment demanded

Mitchell suggested strengthening coalitions "that demand just policing, laws and policies that benefit both communities".

Many interviewed for this article preferred to use the word uprising, instead of riots. It was "a demanding of equal and fair treatment", Fields pointed out.

Smith-Pollard said "rioting or looting" is a strategy that gets attention but isn't sustainable.

"We also understand why people do it because a riot is the voice of the unheard," she said.

Compared with 30 years ago, ethnic groups are engaging each other more, there is also more accountability because of activism and technological advances, but activists and experts said more is needed to overturn "a system of racism".

"Until you've lived it, and walk in the shoes of racism, until you've been followed around in a store when you are just trying to shop; until you try to return an item of clothing into a store and they accuse you of stealing it; until you stood at a counter, and have someone white just walk in front of you like you are invisible, which happens day after day after day with me. Until you've lived that life, you don't really understand how it makes your heart feel," Fields said.