Scientists on trail of 'Deltacron' hybrid

A hybrid of the Delta and Omicron variants is popping up in several European countries and has made its way into the United States, researchers said.

Experts said it is still too early to worry about the new variant of the coronavirus, which they said is unlikely to spread easily.

The hybrid, dubbed "Deltacron" by some scientists, has yet to be designated with its own official name. It is a recombinant virus that carries genes from both Delta and Omicron.

Two independent cases of the hybrid have been found among 29,719 positive coronavirus samples sequenced between November and February by scientists from Helix, a lab based in California. The study was published on Saturday on medRxiv, the preprint server for health science papers, and has yet to be peer-reviewed.

Previous studies have identified cases of Deltacron in Europe. Scientists from IHU Mediterranee Infection found three patients infected with the hybrid in southern France. The team's report was published on March 8 on medRxiv.

In a March 10 update, an international database of viral sequences reported 33 samples of the new variant in France, eight in Denmark, one in Germany and one in the Netherlands, reported The New York Times.

"The fact that there is not that much of it, that even the two cases we saw were different, suggests that it's probably not going to elevate to a variant of concern level "and warrant its own Greek letter name, said William Lee, chief science officer at Helix, to USA Today.

During a World Health Organization media briefing on March 9, WHO's COVID-19 technical lead Maria Van Kerkhove also acknowledged the variant, saying that there are "very low levels" of the recombinant's detection.

"This is something that is to be expected, given the large amount of circulation, the intense amount of circulation we saw with both Omicron and Delta," she said.

Studies underway

Van Kerkhove said scientists have yet to see any change in severity with this recombinant, but there are many studies are underway.

"Unfortunately, we do expect to see recombinants because this is what viruses do, they change over time," she said, adding that the virus is infecting animals, with the possibility of infecting humans again.

"So, again, this pandemic is far from over. We cannot allow this virus to spread at such an intense level."

The variant is extremely rare and has not yet displayed the ability to grow exponentially, according to experts interviewed by the Times.

Etienne Simon-Loriere, a virologist at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, told the Times that the gene that encodes the virus' surface protein, known as spike, is almost completely derived from Omicron. The rest of the genome comes from Delta.

The spike protein is essential when it comes to invading cells. It is the main target of antibodies produced through infections and vaccines. So, the antibodies that people developed against Omicron-either through prior infections, vaccines, or both-should work just as well against the new recombinant, Simon-Loriere said.

"The surface of the viruses is super similar to Omicron, so the body will recognize it as well as it recognizes Omicron," he said.

Today's Top News

- China to apply lower import tariff rates to unleash market potential

- China proves to be active and reliable mediator

- Three-party talks help to restore peace

- Huangyan coral reefs healthy, says report

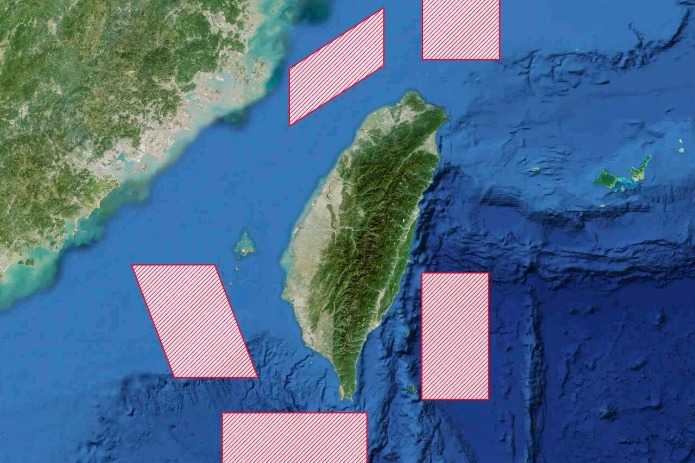

- PLA conducts major drill near Taiwan

- Washington should realize its interference in Taiwan question is a recipe it won't want to eat: China Daily editorial