Peninsula tightrope both taut and fraught

After a pandemic-plagued year in which tensions on the Korean Peninsula grew, analysts see a bumpy road ahead for US-DPRK talks and inter-Korean relations beset by mutual distrust.

At the start of last year, stakeholders were waiting to see what foreign policy the United States would adopt toward the Democratic People's Republic of Korea as President Joe Biden took office in January.

But it was not until late April that Washington's policy review of pursuing "calibrated" diplomacy arrived, touting a longtime cliche that Pyongyang dismissed as a "spurious signboard" to cover up US "hostile acts".

Repeated perfunctory statements by the US that the "ball is in the North's court" raised doubts over whether the US is willing to make a positive gesture to the DPRK, analysts said.

During the first half of last year, the US held separate bilateral talks with Japan and the Republic of Korea, and senior national security officials from the three countries met to talk about how they should deal with the DPRK.

However, the DPRK issue is just a cover for strengthening a trilateral military alliance in Northeast Asia, because US administrations have tried to shift their strategic focus to the Far East, the so-called Indo-Pacific, said Li Nan, a researcher with the Institute of American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

The US also wants to exert more pressure on Pyongyang, Li said, adding that keeping tensions on the peninsula high could help bolster Washington's ties with its allies.

Zhan Debin, an international relations professor at the Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, said: "But the DPRK has a strategic confidence that is stronger than ever since it has sought a road of self-reliance, so it won't easily yield to outside pressure."

Kim Jong-un, top leader of the DPRK, has turned to seek economic growth and improve people's lives amid the pandemic since he charted the course during a key party meeting at the beginning of last year.

It is clear that the DPRK issue is not a priority of the US and that flawed talks between Kim and former US president Donald Trump have deepened mutual distrust, Zhan said.

"After the 2019 Hanoi summit ended without an agreement, Kim figured out that the only way is to boost domestic economic development."

As Washington showed no signs of budging on its call for sanctions relief, Pyongyang was seen as upping the ante last year.

Last Wednesday Pyongyang fired a suspected ballistic missile into its eastern waters, according to the ROK and Japanese militaries, the first such launch this year.

This came after the country conducted several missile tests said to be partly against ROK-US joint military drills, including launching a hypersonic missile in September and a new-type submarine-launched ballistic missile the following month.

Casting shadow

In addition to demanding what the DPRK calls "hostile policy" to stop, it started to call on the ROK and the US to cease "double-dealing" standards, a reference to the allies casting its missile tests as "provocations" while justifying their own as deterrence against Pyongyang.

The rising tension cast more uncertainty over prospects for peace on the peninsula, observers said.

However, there was once a silver lining. The restoration of inter-Korean communication lines in July after more than a year of suspension raised hopes for a thaw in cross-border relations.

But gloom set in again in August as Pyongyang protested over a summertime ROK-US military exercise. The lines were back up and running again in October.

Then came Seoul pushing for an end-of-war declaration.

Seeking to reengage with the DPRK, ROK President Moon Jae-in made the call in an address to the United Nations General Assembly in September.

The DPRK and the ROK are still technically at war after their 1950-53 conflict ended in a cease-fire.

It was the fourth time Moon had made such a call since 2018, media reports said, and it received a cool reception. Pyongyang rejected the proposal as premature and said there was no guarantee it would lead to the US abandoning its hostility toward the DPRK.

US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said in late October that Washington and Seoul "may have somewhat different perspectives on the precise sequence or timing or conditions for different steps". He made the comment in a news briefing that was widely seen as an illustration of how wide apart the two allies remain over the end-of-war issue.

"The US wouldn't be happy to see peace between the ROK and the DPRK, which would weaken the US-ROK alliance," Li said. "The first question would be, 'What about US troops stationed in the ROK?'" The US has about 28,500 troops in the ROK.

Updating plans

Early last month, during their 53rd Security Consultative Meeting in Seoul, defense chiefs of the ROK and the US agreed to update war plans against Pyongyang.

The announcement revealed that the US is unwilling to promote the signing of the end-of-war declaration because it utterly opposes the peaceful spirit it conveys, said Cao Shigong, a researcher with the Chinese Association of Asia-Pacific Studies.

If the US cannot get rid of its self-centered policy and long-standing tradition of hegemony, the declaration could end up with nothing, Cao said in an opinion piece published online.

Looking forward, Li said there is a long way to go and the negotiation of the declaration should also include the DPRK and China.

"The end-of-war declaration is the first step in establishing the peace mechanism on the Korean Peninsula and involves the normalization of US-DPRK relations and the denuclearization of the Peninsula. It should be more than symbolic."

Today's Top News

- Trump says 'a lot closer' to Ukraine peace deal following talks with Zelensky

- China pilots L3 vehicles on roads

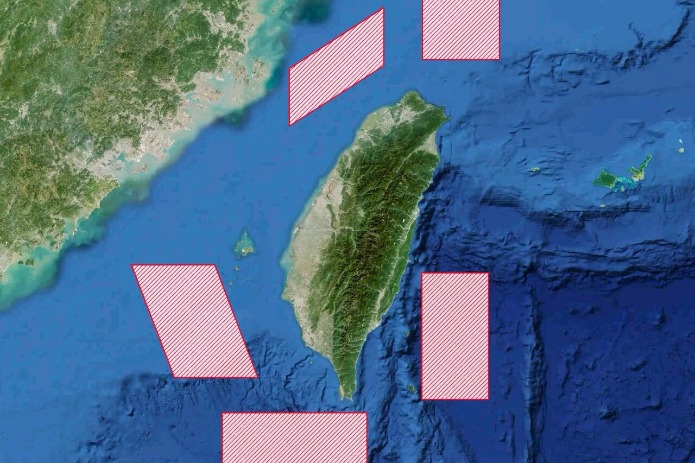

- PLA conducts 'Justice Mission 2025' drills around Taiwan

- Partnership becomes pressure for Europe

- China bids to cement Cambodian-Thai truce

- Fiscal policy for 2026 to be more proactive