Can developer land banks be unlocked?

Long waiting line for a roof

The waiting time for applicants is almost six years. More than 153,900 general applications and over 100,800 non-elderly one-person applications are awaiting action. This wait is the longest in more than 20 years. It was 1.8 years in 2009. The stated Housing Authority (HA) target of three years for new applicants seems unrealistic. The HA pledged to supply 75,000 units from 2011 to 2016. It managed 62,559, a 17 percent shortfall.

The 2016 Policy Address flagged 210,000 units in five years, of which 70 percent - 147,000 - would be public housing. Actual production was 79,099, meeting only 53 percent of the target. Ryan Yip, head of Land & Housing Research at think tank Our Hong Kong Foundation, calculated the deficit of 20,500 units under the 2017 Long Term Housing Strategy for 180,000 units - as equivalent to 1.6 times the area of Taikoo Shing. Yip is pessimistic about the production goal of 15,000 new units a year from 2021 through 2025.

The PRH financing is unsustainable, adds Jacqueline Hui, a researcher at Our Hong Kong Foundation. The HA is meant to use the rental income to cover the construction and maintenance of public housing units. However, the authority is negatively impacted by rising construction and maintenance costs. Under the current arrangements, it is projected to accumulate an operating deficit of HK$490 billion ($62.9 billion) by 2041-42, according to Hui's research.

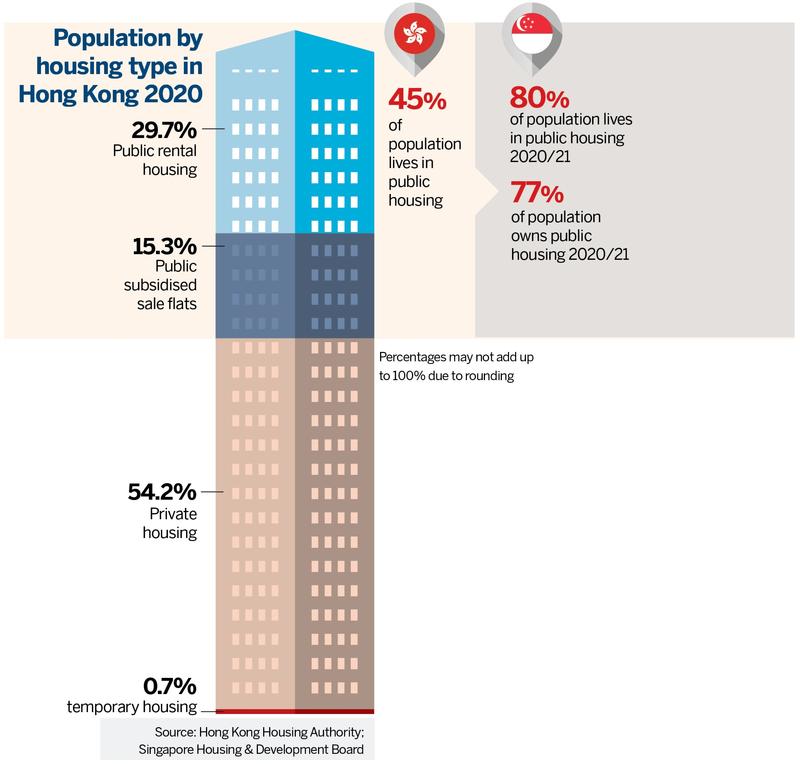

The average monthly rent in the city is HK$20,858, exceeding the median monthly income of HK$18,400. That forces the housing underclass to survive in subdivided flats averaging 132 square feet. The average living space for public rental housing tenants in 2014 to 2020 ranged from 13 to 13.5 square meters per person, while subdivided cells allowed 4.9 sq m per capita, according to a 2019 government survey. Singapore, densely populated with an even smaller land area, provides 30 sq m per person for 81 percent of its residents in public housing.