The VOTE that SHOOK up the WORLD

When China was restored to its rightful place in the UN 50 years ago, many Chinese in the US feted a decision they regarded as nothing but common sense.

For John Lee, Sept 22, 1971, was a day to remember. "It was all about the optimism of youth-young people pursuing what we believed to be right," Lee, now 72, says.

That day the 22-year-old and his elder brother Corky were among 900 people who marched in Manhattan, New York, near where United Nations headquarters is located, as-to quote a report carried by The New York Times dated Sept 19, 1971-"127 UN delegations are busily lobbying and being lobbied on the issues of whether Peking should be seated, whether Taipei should be expelled and whether such an expulsion would be an 'important question' and thus require a two-thirds vote instead of the usual majority".

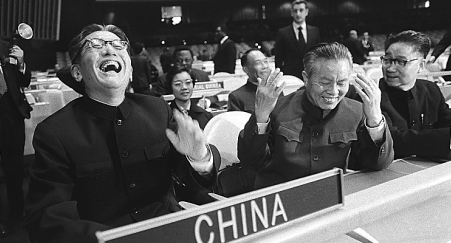

A month later, on Oct 25, the 26th UN General Assembly rejected the "important question" resolution, a procedural maneuver successfully used by the United States in the 1960s to block Beijing's effort to seek representation in the UN. The assembly then proceeded to pass Resolution No. 2758 with an overwhelming majority: 76 votes for, 35 against and 17 abstentions.

"The General Assembly... decides to restore all its rights to the People's Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the United Nations, to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it," the text of the resolution said.

Francis Plimpton, a US diplomat who was part of the US delegation to the UN in the 1960s, wrote: "The presence of Peking will strengthen the status of the UN as a ready made forum for multilateral diplomacy, a place where representatives can quietly negotiate among themselves without the disadvantages of trying to handle multifaceted problems by disparate bilateral contacts or by multiparty ad hoc conferences."

Lee, calling the UN adoption of the resolution a "breaking point", sees the demonstration as the harbinger of that historic moment.

"It was enlightening to see significant numbers of Chinese coming out in public in support of the PRC. It had been largely a private endeavor up to that point. I dare say that many who had been brought in by the KMT(Kuomintang) to march on their side were quite surprised to see us."

Between 1946 and 1949 the Chinese Communists, led by the Communist Party of China, were at war with the Nationalists, led by the Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT. Despite strong backing from the US, the Nationalists, with Chiang Kaishek as the paramount leader, suffered a humiliating defeat before fleeing to Taiwan for a foothold there. On Oct 1, 1949, the People's Republic of China was born.

For the next 22 years, with what the Chinese government calls "the manipulation of the United States",Chiang Kai-shek continued to send his people to New York to represent China at the UN. This despite Beijing's ceaseless "struggle to restore China's lawful seat" and despite what Lee calls "the apparent absurdity of the arrangement", against which the brothers and their fellow pro-Beijing protesters had demonstrated.

"I remember seeing the KMT buses rounding the corner of 42nd Street and coming into our view from across the street," Lee says.

"What followed was a massive shouting match."

Fearing a physical clash, police, massing on side streets, asked Lee's group to stop where it was, a couple of blocks from its planned destination, the UN Plaza. Hugely disappointed, Lee, who had been acting as the group's liaison person with the police, found himself arguing fervently with an officer, watched on by the legion of camera-hauling international reporters.

"All the time I was thinking to myself: 'Dad's going to see this on TV tonight'," Lee says, referring to his late father, who watched the evening news religiously, and who had dropped by Lee's apartment that morning casually asking about his son's plans for the day.

The father came again a week after the demonstration. "'You know, there's a great deal of danger those supporters of the (Chinese) mainland undertook ... But what's right must be expressed.' That's what my father said, and he just left it at that," says Lee, who later studied law and went into practice on the West Coast.

"Everyone was watching," was how Charlie Lai, one of the founders of the Museum of Chinese in America in Manhattan, describes the mood of Manhattan Chinatown in the months before the UN resolution. "It's all about if you are not strong enough, they could ignore you."

Lai was also thinking about the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first immigration law in the US to exclude an entire ethnic group. Enacted in 1882, it barred almost all Chinese from entering the country except for scholars, merchants and diplomats. Although the law was revoked in 1943, it was not until 1965 that Chinese were finally allowed to come in relatively large numbers.

That was the year when Lai, 9, with his parents and five siblings, arrived in New York from Hong Kong, where the couple from southern China had previously sought refuge during Japan's invasion of China in the 1930s and 40s.

"My parents worked all the time in the restaurants and garment shop," Lai says. "They didn't come home and talk about politics. And since they left the mainland in the 1930s they were not necessarily in favor of the Communists or Chiang Kai-shek. Yet the idea of Taiwan representing China just didn't quite make sense to them. They saw themselves as Chinese first and foremost."

Having devoted much of his time in the 1980s to amassing the museum's earliest collection, sometimes by trawling Manhattan Chinatown salvaging discarded newspapers and thrown-out family photo albums and letters from the roadside, Lai says that "whatever happened between China and the US had repercussions here in the local Chinese communities".

"With the growing antagonism in the US against 'Communist China' and with the advent of McCarthyism in the 50s, every Chinese here in this country was a suspected communist," he said. "The FBI, the Internal Revenue Service and the immigration office were trying to weed out communist sympathizers from whatever information they had. That really put the whole community on edge."

Lee, born to his immigrant parents in New York in 1947, says:"When the red scare broke out here in the 50s, the right-wing, pro-Taiwan elements were very, very good at organizing the Chinese communities, more out of fear than anything else."

The result was "false alignment with Taiwan" and the "repression a number of progressive organizations within the Chinese communities had undergone both voluntarily and involuntarily".

"Leading up to the PRC's admission to the UN, we went over this period of time when we started to rediscover the historical treatment of Asian Americans in this country,"Lee says. "And one of the things that came to light-apart from the Chinese Exclusion Act-was the active attempt by the US government to suppress all progressive and leftist political activities within our community, after the founding of the People's Republic of China. It was also around this time that people started realizing that the PRC was on the rise, that it was developing its political power on a global scale."

Lee became affiliated with "a collective of left-leaning students" in New York that sought to provide basic social services-medical checkups, for example-to those who lived in Chinatown. The Marxist-socialist-oriented group also served as the community's "primary outlet of (Chinese) mainland news".

"What surfaced was a more positive image of China, one that allowed us to take pride in our own heritage," Lee says.

At this time the Vietnam War was raging, and Lai and his fellow high school friends were discussing the possibility of being drafted into the army.

"In the context of the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement, many young people started to question the American system and to look at other societal models, the Soviet and the Chinese ones, for example."

As the level of political consciousness grew across all communities of color throughout the 60s, communication and collaboration among all students of color also grew, Lee says.

"It was generally acknowledged that the PRC was a leader and supporter of Third World liberation struggles, a fact reflected in US domestic politics and foreign policy."

The New York Times account of the September 1971 demonstrations offers proof. "The pro-Peking demonstrators were mostly young and long-haired, and included a number of blacks, Puerto Ricans and whites," it said. "Their ally was billed as a united front of Third-World forces, and their slogans and posters, a few of which were in Spanish, reflected this position."

During the buildup to the demonstration, Lee's group "had people out passing around leaflets throughout Manhattan Chinatown as well as various campuses throughout the city.

There was "a steady escalation" by the Taiwan supporters, who wounded members of Lee's group and threatened them with violence "if we don't pull our propaganda team from the streets", he says. And he recalls meeting one young woman at a KMT literature table outside a Chinatown building.

"What struck me about her was that she had a southern accent. I and a couple of my companions struck up a conversation with her, and it turned out that she and her family had been bused from New Orleans all the way up to take part in the pro-Taiwan demonstration. The KMT were literally paying people up to $50 each to take part."

Yet the feelings among certain segments of New York's Chinese community were "quite raw" after the PRC triumph at the UN, Lai says. "The KMT had for many years focused enormous attention and resources on our communities in their efforts to cultivate support for Taiwan and the Nationalists. And remember, those were the days when the only business exchanges we had were with Hong Kong and Taiwan. It was no surprise if people didn't want to rock the boat."

As some residents of New York's Chinatown were harboring apprehension and even misgivings about PRC replacing Taiwan in the UN and its potential political implications, a cloud of "suspense" was hanging low over Patricia Koo Tsien and her fellow Chinese colleagues at the UN.

"These have been difficult days, and the future is bound to continue with some suspense," she wrote to her father, who lived in New York at the time, in a letter dated November 1, 1971, one week after Resolution No. 2758 was adopted.

"Although the general assurance is that the Chinese staff with Nationalist passports will not be affected, I think each case will probably be decided individually," she wrote. The letter and two others were provided to China Daily by Tsien's daughter Ying-Ying Yuan.

The all-too-wary US media were quick to pick up concerns such as Tsien's. "The some 400 Chinese in the UN Secretariat may present a problem," a New York Times article said. "Most are in uncontroversial posts as interpreters, translators and clerks, and in any event all members off the Secretariat are supposed by the explicit provisions of the Charter to be international civil servants responsible not to any country but only to the UN. However, experience with other Communist UN members shows that in general they treat their nationals in the Secretariat as full-fledged employees of their own Government and owing allegiance only to it."

Tsien's father V. K. Wellington Koo (Koo Vi Kyuin or Gu Weijun in modern Chinese pinyin), although in his 80s at the time, had every reason to be informed.

On June 26, 1945, as World War II was drawing to a close, Koo led an eight-person Chinese delegation at the signing of the UN Charter in San Francisco. Thanks to the fact that, alphabetically, China was the first country among the 50 whose representatives attended, Koo was the first person to sign, followed by the other Chinese delegates including Dong Biwu, a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party.

During the Chinese civil war between 1946 and 1949, Koo, as the Nationalist Government's ambassador to the US, worked tirelessly to drum up US support for the KMT. After Chiang Kai-shek's defeat, Koo continued in his role until 1956, focusing on maintaining the alliance between the US and Taiwan.

In fact, given the animosity between Beijing and Taiwan at the time-the fight for the UN seat had certainly aggravated the matter-even the UN secretary-general Kurt Waldheim felt compelled to send a mild alert to Tang Ming-chao (Tang Mingzhao), whom he appointed under-secretary-general in April 1971, following the UN tradition that each of the five permanent members of the Security Council be entitled to a top-level post in the UN Secretariat.

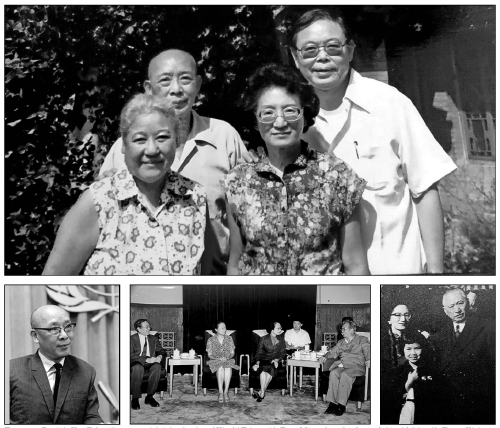

In Serving the United Nations: a Collection of Memoirs of Chinese Former International Civil Servants, a book coedited by Tsien and her fellow Chinese colleague Shing-Yi Huang, the ambassador's daughter recounted the incident:

"When Mr Tang was appointed to the Department of Trusteeship and Non-Self-Governing Territories he was informed by the secretary-general that the daughter of Wellington Koo was a member of the department and that if he found it inconvenient, I could be transferred to another department," she wrote. "But Mr Tang graciously told me of his decision to keep me, and this was for me the beginning of a new experience.

"Not only did Mr Tang not avoid me, but he would often call me in to ask me for some information or to meet his American friends. He would then introduce me as the daughter of Ambassador Koo."

In fact, none of the aforementioned worries that had informed what Tsien called "corridor talk" among UN's Chinese employees materialized.

"Just a note to tell you that word has gone around that Huang Hua told the SG (secretary-general) that the Chinese delegation does not intend to affect the continued service of the Chinese staff in the secretariat,"Tsien wrote to her father on Nov 11,1971. Huang, the head of the PRC's first permanent mission to the UN, would later met Tsien many times at tea parties given by the mission to Chinese UN staff, and as her host during her visits to China in the 1980s.

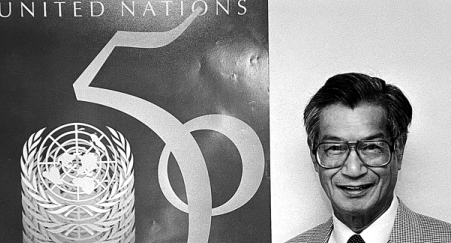

In fact, immediately after Resolution No 2758 was adopted, the 26th session had a position paper prepared by Shing-Yi Huang in anticipation of the resolution's possible effects on personnel arrangements in the secretariat.

"The PRC decision ... is a correct one as it upheld the SG's authority," says Huang, who by his own account was "enjoying his (professional) golden age" in the early 1970s. "It's also a smart one for the PRC to retain the multitude of veteran Chinese staff members who are well experienced and have distinguished themselves in many fields of UN activities."

A friendship soon developed between Tsien and Tang, so much so that years later Tsien would take her daughter Ying-Ying to visit Tang in his home in Beijing. But before that was a trip by Tsien and her husband Kiachi Tsien in the autumn of 1972 to see what Tang called "the new China".

"Arrangements were made for us to visit various places and institutions," Tsien wrote in Serving the United Nations. "Wherever we went we received detailed briefings. We thoroughly enjoyed this educational trip, which was a welcome for us to visit China on future home leave."

In doing that, Tsien found her life trajectory paralleling that of her friend Shing-Yi Huang: both first came to the US around 1947, and both waited for 25 years to return home.

"I was educated to be a diplomat at the Central Political University in China's wartime (World War II) capital Chungking (Chongqing) and joined (the Nationalist Government's) Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a junior officer," Huang, 98, says. "Two years later I was sent by the ministry to its embassy in Washington, DC to serve as an attache."

That assignment allowed Huang to further pursue studies in international relations at George Washington University, at a time when civil war was being fought in China between the Communists and Nationalists. He gained his degree in 1949, the year the People's Republic of China was founded. In early 1952 Huang joined the UN "in its new Secretariat building" in New York, after beating his fellow contestants in a highly competitive exam.

"I found to my surprise that quite a few Chinese colleagues were ready to resign and take their families back to China to participate in its reconstruction," says Huang, who acknowledges "a feeling of being abandoned by the new government" as visits to China became no longer practical.

The Chinese Government started to allow Chinese staff members in the UN to use the UN laissez-passer, he said, instead of a passport, to enter China around 1970, the year before Resolution No 2758 was adopted. When Huang returned with his family in the summer of 1972, he found himself "a guest of Chairman Mao".

"In Hangzhou we stopped at a tea shop and tasted some tea," Huang says. "My children wanted to buy a porcelain teacup with store inscription. The clerk said he had to check with the manager. The manager's answer was: 'Sure, they are the guests of Chairman Mao'."

Tang, who was then the highest-ranking Chinese from the PRC in the UN Secretariat, made a point of encouraging such trips.

Born in southern Guangdong province, he migrated to the US with his parents in the 1920s, before returning to China to attend high school and university, where he joined the Chinese Communist Party in 1931.

Back in the US in 1933, Tang studied Western contemporary history at the University of California, Berkeley. Throughout the 1930s and 40s he remained an active Party member, co-founding the Chinese-language newspaper China Daily News in New York to raise awareness and support among overseas Chinese about the plight and struggle of their home country.

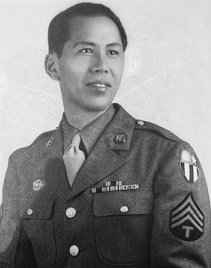

The paper was founded with the support of the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance, a labor organization dedicated to improving the lives of those in an occupation heavily identified with Chinese Americans in the first half of the 20th century. (Lee's parents opened their first laundry in New York in 1946, after his father was discharged from the US Army Air Corps at the end of the World War II.)

A co-founder of the paper was Ji Gongquan, whose son Ji Chaozhu, with Tang's daughter Nancy Tang (Tang Wensheng), acted as Mao Zedong's most-trusted interpreters during the 1970s. Nancy Tang can be seen sitting behind Huang Hua when the PRC delegation took its place in the General Assembly in New York on Nov 15, 1971, three weeks after the resolution. Both interpreted during president Richard Nixon's visit three months later. Ji Chaozhu also served as UN under secretary-general for development support and management services from 1991 to 1996, a "distinguished leader with energy and vision", to quote a UN tribute made when he died in April last year.

Through his education, as well as his close involvement with both the alliance and the newspaper, Tang Ming-chao straddled the dual worlds of Chinese in the US at the time: one was inhabited by the parents of Lee and Lai and their fellow Chinese laborers; the other by Tsien and Huang and their relatively small circle of highly educated, elite Chinese.

Above all, he understood the cultures and concerns of both groups, as well as their longing to reconnect with China.

Realizing the key role he played in bridge-building, Tang had "gone across the street to talk to people",Yuan says, referring to his relentless effort to win hearts and minds, which he also did through "his even temper and his genuine open-minded and democratic administration", to quote Yuan's mother Tsien.

On Tang's appointment as under secretary-general of the Department of Political Affairs, Trusteeship and Non-self-governing Territories, which he later asked to be renamed the Department of Political Affairs, Trusteeship and Decolonization, The New York Times carried an article titled "Job with a Needle". "They (the Chinese) accepted (the appointment), apparently deciding that the new post would strengthen their influence in Africa and Asia-and give them a chance to needle Western powers on colonial issues," it said.

For the next eight years, Tsien, specialized in Portuguese territories from that country's colonial era, and with more than 20 years of UN experience behind her, became Tang's de facto right-hand lady, accompanying him during multiple UN missions overseas to negotiate, monitor and facilitate the decolonization process.

"During Mr Tang's term of office from 1972 to 1978, some 14 territories became independent," Tsien later wrote. "The 1970s were a memorable period for the United Nations in the process of decolonization, in which Mr Tang was able to play an important part. In his personal capacity he was much respected for his high principles, his integrity and his never flustered serenity."

When Tsien retired in 1979 she immediately wrote to notify Tang, who had left the UN earlier that year and whom Tsien would meet in Beijing many times before he died in 1998. Tsien made her last visit in 2005, 10 years before she died in 2015 aged 97.

Contrary to the prediction by some US media in 1971 that the Chinese would be "rubbing against and being rubbed by their East River colleagues" (UN headquarters occupy a site adjacent to the East River),Shing-Yi Huang discovered deep-rooted common ground with "my colleagues from the PRC", who also "lived up to the high standards of competence, loyalty and integrity prescribed in the traditional Chinese civil service system".

Huang's last trip to China was in the spring of 2014. The then 91-year-old visited his hometown Ningbo, in Zhejiang province, where "my late wife was buried and so will be myself to share the same tomb", to use his words.

On Oct 1, 1984, after the end of Shing-Yi Huang's UN service, he found himself in Tian'anmen Square, Beijing. As a guest to China's National Day parade, Huang watched as a group of students from Peking University walked past, unfurling a banner greeting the country's top leader with a "Hello, Xiaoping!"

Caught by surprise, Deng Xiaoping, who was at the helm of the country's reform and opening-up drive, smiled and waved from atop Tian'anmen Gate. China had opened a whole new chapter.

In retrospect, Lai, a Princeton University graduate whose involvement with Manhattan Chinatown has proven to be lifelong, says that China asserting its place in the UN and its subsequent development has accorded those around him with a "unifying perspective".

"To see a group of people sitting around a table about to begin a Peking-versus-Taiwan argument, when one of them stood up and said,'Shut up already! Are we proud to be Chinese?' and the rest all answered,'Yes! We are proud to be Chinese!'That was a scene one was likely to encounter in Chinatown after October 25, 1971. And it's very, very powerful."

According to Lai, the land reform and the redistribution of property and wealth that had been carried out in China throughout the 1950s and 60s had alienated many members of overseas Chinese communities.

"The relatives of these people, who had bought land and property with money sent home from overseas, were often viewed as bourgeoisie and targeted," he said.

"Yet when China was weak, our overseas Chinese had truly fared more poorly. So despite being upset by the political upheavals the PRC had been through and its impact on their families, our community members had truly found comfort in the fact that China was given what it demanded, that it had finally become strong."

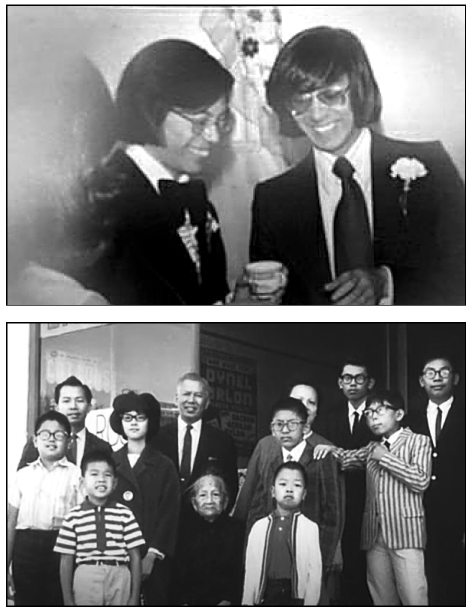

These days Lee hangs on to his memories of the demonstration as he recalls his elder brother Corky, who died in New York in January aged 73 as a result of COVID-19. His dedication to photographing Asian Americans had led to a tribute in one newspaper calling his life "a ceaseless act of creative intervention in a history shaped by erasure".

"Corky documented the event with his camera, at a time when no one else had even thought of recording," John Lee says. "Corky himself visited China in 1972, as a member of the Asian American Student Travel Delegation."

It was in February of that year that president Richard Nixon visited China in what he would call "the week that changed the world".

"The PRC's success in its petition to be seen as the rightful spokesperson for China opened up not only diplomatic and other channels for the country, but also people's minds here," Lee says. "After that we slowly started to see Chinese flags in Chinatown."

Lee's father died aged 74 in 1982.

"My father always believed that neither could China be ignored, or America maintain her hegemony, for long," he says. "He was right. As for me, if I needed to do it (the demonstration) again, I would, aged 72."

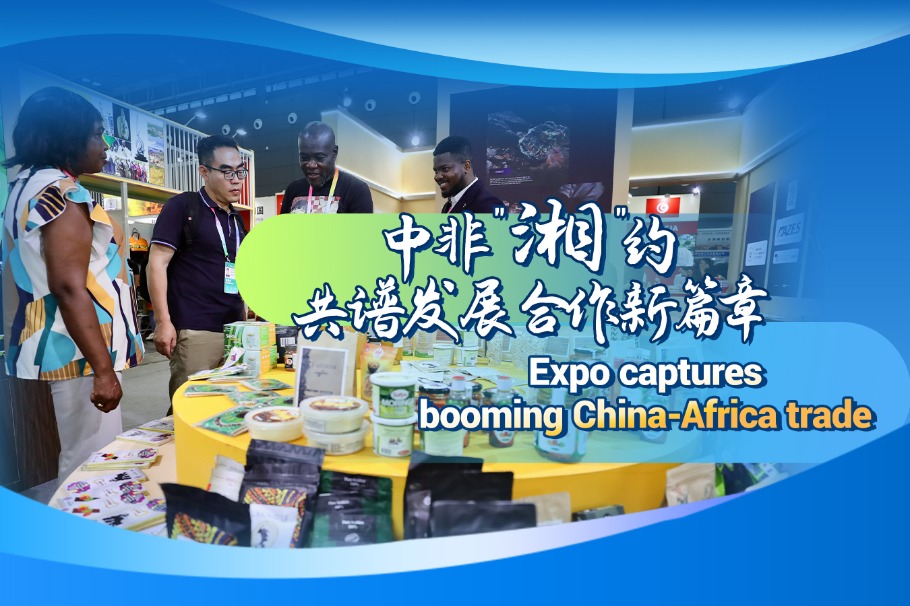

Today's Top News

- Top political advisor stresses jointly guarding Taiwan Strait peace, advancing reunification

- China, Central Asia witness deepened economic, trade ties

- Xi's article on guiding economic, social development with medium and long-term planning to be published

- Restraint and dialogue vital to de-escalate Israel-Iran crisis: Editorial flash

- 'No Kings' protests across US target Trump policies

- China criticizes US tariff narrative as 'one-sided, misleading'