A man of character

Fascination with the history of Chinese language has been a driving ambition, Wang Linyan reports.

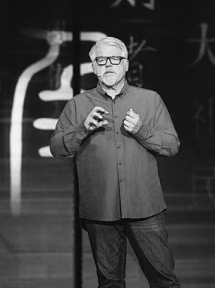

For the past three decades, Richard Sears, 71, has been focused on one thing: telling stories behind Chinese characters.

"What I do is to take every character and try to find its original pictographs and explain its original logic," he says.

Sears, nicknamed Uncle Hanzi by Chinese netizens, even designed a website for his sole passion. Hanzi means Chinese characters.

In order to explain the Chinese characters, he has built a database of 31,000 oracle bone characters from the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC), 24,000 bronze characters from the Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century-256 BC), and 48,000 seal characters (or zhuanti) of the Qin (221-206 BC) and Han dynasties (206 BC-220), as well as 11,000 from the book Shuowen Jiezi (an explanation of Chinese characters). The book was written in AD 121 in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), one of the earliest books on Chinese characters' forms and origins.

Early interest

His interest in Chinese language and characters goes back to 1972, when he was a 22-year-old physics major at Portland State University in Oregon, the United States.

"I had checked across Canada and the US. And I was on my way to Africa," he recalls. "I wanted to see the world. But then I realized only 7 percent of the world speaks English as a mother tongue. So I wanted to know what it was like to speak another language."

Sears bought a one-way ticket to Taiwan to learn Chinese.

In Taiwan, Sears supported himself by teaching English. Two years later, he returned to the US to finish his study and went on to get a master's degree in computer science. He became a researcher at a US national lab after graduation, later worked as a software engineer at several companies in Silicon Valley.

By 1990, at 40, Sears was already pretty fluent in Chinese, but he did not know how to read, so he decided to learn to read and write Chinese. An average Chinese, for example, a high school graduate, knows about 5,000 characters and 60,000 character combinations. But to Sears, the characters were complex with many strokes and almost no apparent logic.

He says he found on some rare occasions, when he could get a step-by-step evolution of a character from its original pictographic form with an explanation of its original meaning and an interpretation of its original pictographs, it would suddenly become apparent how all the strokes had come to be.

"I'm a physicist, so I don't like blind memorization. I knew that Chinese characters came from pictographs and I wanted to know the stories behind the Chinese characters."

But all he had at that time was a book in English that was based on Shuowen Jiezi.

Seeking answers

As he studied, Sears realized quickly that many of the explanations could not possibly be true. Even the experts had many opinions. He decided to computerize it, so that he could "separate good opinions from bad ones".

In the 1990s, computers were primitive. Sears knew Chinese archaeologists had studied characters on oracle bones. And he found important books such as Guwenzi Gulin (explanations of ancient Chinese characters), Liushutong (methods and examples of the invention of Chinese characters) as he talked to experts during his trips to the Chinese mainland and Taiwan.

What happened in 1994 made Sears realize time was of the essence-he suffered a nearly fatal heart attack.

"I did not know if I would live another hour," he says. "And then I had my first heart surgery and I had to think about my life. I had to plan as if I was going to die maybe in a year. So I decided to computerize Shuowen Jiezi."

Sears scanned the book and started to computerize the ancient characters. He then scanned about 96,000 other ancient characters from three more books, Liushutong, Jinwen Bian (a compilation of Chinese characters on bronze ware), and Xujiaguwen Bian (an updated compilation of Chinese characters on oracle bones).

The database of ancient characters came into being, but that was not the end of the story. He wanted to explain the step-by-step evolvement of these characters from the original pictographs to the modern simplified forms.

Over thousands of years, Chinese characters have gone through at least seven stages of transformation from oracle bone character to bronze character (jinwen), then from xiaozhuan to the present simplified characters.

Sears spent about $300,000 from his own savings on the website and later he lost his job in Silicon Valley due to the slack economy. He even worked on a night job as a security guard for several years so that he could study characters at night and get some rest during the day. "I didn't earn much, but at least I had time to read Chinese books," he says.

Website draws clicks

He finally got his website up in 2002 and named it Chinese Etymology, where visitors can check for free the evolvement of Chinese characters in various forms.

He continued to work on the maintenance of the website. In 2003, Sears moved to a rural area in Tennessee to work as an engineer for Tennessee Valley Authority.

Between 2002 and 2011, the website would get 11,000 or 15,000 hits a day, and donations on the website would be no more than about $100 a year.

But then in January 2011, it suddenly went up to 600,000 visitors in one day. That was when he became Uncle Hanzi, a nickname from Chinese netizens, after one of them shared his website on Chinese social media. That week, he received 3,000 emails.

"I like the nickname. I've been studying Chinese characters since I was 40. Thinking of the money and energy spent, most people thought I was crazy. Now finally people think it's worthwhile," he says.

Some visitors are keen to learn Chinese characters, others are researchers looking into Chinese etymology.

More people got to know Sears and his story after he appeared on a number of shows, including First Class for New Semester, an annual program for primary and secondary school students on China Central Television, and Chinese Bridge on Hunan Satellite TV.

Currently, the website receives about 300,000 visits every month on average across more than 170 countries and regions. Half of the hits are from China.

In addition to the database, he has explained the etymology of 15,000 modern characters on the website, which means 99.99 percent of all the characters that the average Chinese is going to see.

"You can put in any simplified character or any traditional character. And you can see the change over 3,500 years. And you can see the logic explained," he says.

For example, the character jia (home) has a rooftop and a pig underneath. The pig is there to share one roof, he explains. In southern China where it rained a lot, people would put the house on stilts, so if it flooded, the inside of the house would not get wet. So the pigs lived underneath the house.

Sears says he likes to go out in the countryside and talk to farmers and look at how they grow their crops.

"And I look at ancient technology, spinning and weaving. And I think does this correspond to some ancient Chinese character? So I learn more by going out in the Chinese countryside, looking at how people do things."

He says there are probably 400 characters that are based on spinning and weaving. "Like the word for grandson, one character component looks like a cheese ball. That's because it was a job of small children to spin thread. So that would be the sunzi (grandchild). So this is very interesting."

Through years of study, Sears says he has found that many modern Chinese have blindly memorized Chinese characters, and they don't understand that characters come from pictographs. "But if you understand the ancient Chinese pictographs, you can understand a lot about ancient Chinese people," he says.

"So if you know the history of Chinese characters, then you know something about everyday life of ancient Chinese."

If you look at the sky, can you tell where huangdao (ecliptic) is, Sears asks.

"Every ancient Chinese knew where it was," he continues. "It's the star that goes from due east to due west. And it was extremely important to ancient Chinese. It was a matter of life and death.

"It was important to understand astronomy. That's the way they arranged agriculture. But most people today don't think about that. They hear the words, but they don't understand what it's about."

Staying in China

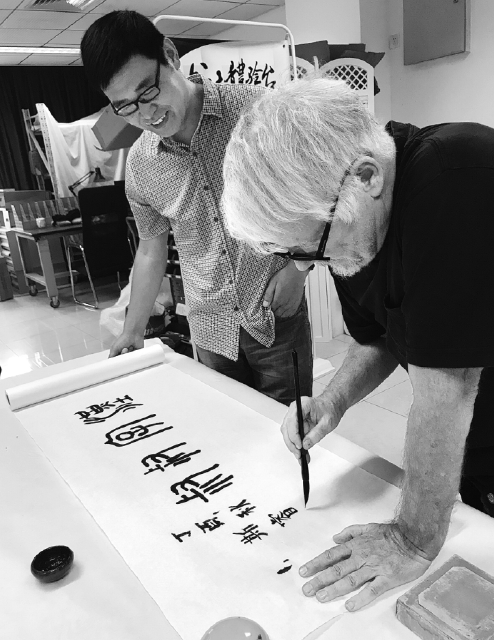

After he visited Tianjin in 2012 to receive an award at an event hosted by Tianjin Satellite TV, Sears decided to stay in China. He worked different jobs in Tianjin, Beijing and Anhui province before finally settling down in Nanjing seven years later in 2019. There he worked with Nanjing Retinar Information Technology Co to transform the images of different forms of the same Chinese characters into animation for teenagers, using augmented reality and pattern recognition.

In June last year, Sears was awarded Jinling Friendship Award by the Nanjing local government in Jiangsu province. Six months later, the 70-year-old received his long-awaited permanent residence permit for foreigners, or the Chinese "green card".

In September, Sears set up his studio in Nanjing as part of the local authority's plan to cultivate talent in the culture sector. The studio focuses on applying AR, animation and artificial intelligence to telling stories of Chinese culture and character origins. They have made more than 60 such videos in English with Chinese subtitles for Bilibili, a video website.

"They have both entertainment value for young Chinese and educational value and can teach the origins of Chinese characters," he says.

"We also want to make videos with a high educational value for other platforms both for Chinese and foreign learners of Chinese characters. This will be a comprehensive set of videos, showing the pictographic origins of all of the basic components of modern and traditional Chinese characters."

In the meantime, Sears has been updating the database. "My philosophy is huodao lao xuedao lao (live and learn), so never stop learning."

Today's Top News

- US scholar: China's 15th Five-Year Plan charts path to future

- Coding the law for smart governance

- China ready to take tougher steps over Takaichi remarks

- Mobile judicial teams ensure justice for all

- Historic cross-boundary marathon marks a milestone

- Preparations begin for new space mission