COMPANIONS IN SOLITUDE

Living with the pandemic has led a museum curator to reflect on the way ancient Chinese approached the idea of seclusion-to embrace it rather than fight it.

To be alone or together? That question, evocative of the famous one in Shakespeare's Hamlet, was presented by Joseph Scheier-Dolberg to himself on one of those days last year when the curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was homebound with his wife and young son, in a city ravaged by the pandemic.

While outings were largely limited to hasty walks to the nearby grocery store, exchanges with family and friends, including those with whom the curator had previously not been in active contact, unexpectedly rose. Sitting in his dimly lit study-bedroom in Manhattan, across the desk from his home-schooling son, he contemplated his own state of being, in the same way an ancient Chinese scholar might have done hundreds of years, or even millennia, ago.

And while ancient Chinese looked for answers deep in the forested mountain or in their own backyard that often amounted to "a simulation of nature" to quote Scheier-Dolberg, the curator, in his own effort, has turned to what those literary-minded men came up with over the ages-ink-soaked pieces of painting, calligraphy and poetry, often three in one.

And now he is sharing his findings with museumgoers through an exhibition titled Companions in Solitude-Reclusion and Communion in Chinese Art, on view at The Metropolitan Museum until next August.

"For more than 2,000 years, reclusion-the act of removing oneself from society-has been presented in Chinese culture as an ideal state in which to cultivate the mind and transcend worldly affairs," Scheier-Dolberg says in the exhibition's accompanying wall texts. "At the same time, communion with like-minded people has been celebrated as essential to human experience. Images of people pursuing one path or the other, or combining them in complex and surprising ways, abound."

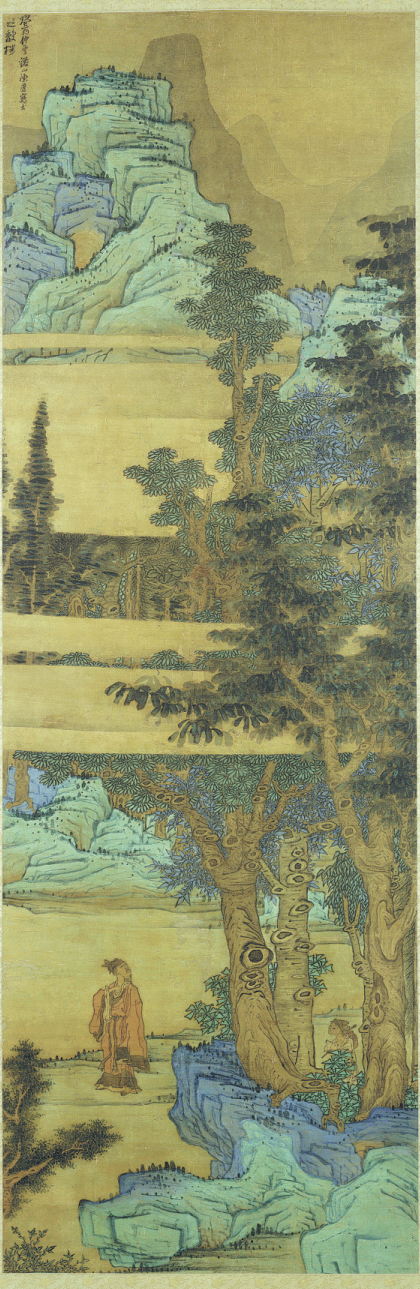

Within those images-about 60 of them are on view-one sees plenty of mountain scenes, although the men that appear in them often seem to stroll rather than scale. The strenuous nature of climbing is replaced by a soothing touch inherent to the genre, one that envelops the figure-usually a scholar-gentleman-as he cruises across the tableau, adding "an extra layer of meaning" to what would otherwise be a landscape painting as seen in the artistic traditions of the West.

One example is by the 17th-century calligrapher and poet Chen Hongshou, whose rendition of the theme puts a scholar-gentleman amidst a green-tinted mountain vista, trailed by a servant boy carrying the jug of wine requisite for "unlocking creativity", to quote Scheier-Dolberg. The fruit of that creativity, most likely to come in the form of writing, stood the chance of inspiring more than a few other works of art executed in the same spirit.

"Painting and literature-and by extension calligraphy-were inseparable," said Wang Yimin, an expert on ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy at the Palace Museum in Beijing. "And one can only expect to truly understand and appreciate the phenomenon of 'literati painting' in ancient China with that in mind."

The Palace Museum has grown out of the Forbidden City, a sprawling royal palace in which successive Chinese emperors lived between the 15th century and the early 20th century. It is where they presided over their court and hoarded their enormous royal collections of art, of which literati painting, in true reflection of its dominant cultural position, forms a major part.

Wang, calling Chen "a link in a winding artistic tradition", said literati painting can be partly traced to a time when China's educated elite first sought active engagement with politics. He was thinking about the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) and the subsequent Warring States Period (475-221 BC), the end of which marked the beginning of a mighty, unified China.

"Apart from the kings and generals, one group of people who populate this dramatic chapter of Chinese history are the thinkers or scholar-lobbyists," Wang said. "Not content with merely recording their thoughts for posterity, they journeyed from one kingdom to another, and would only stop when assured of the listening ear of a decision-maker, i.e. the king."

While the cutthroat rivalry between the kingdoms, which were constantly at war, worked in the interests of the lobbyists, those who succeeded were still few and far between. Perpetually on the road with an increasing sense of frustration, those who failed to make an impression remind Wang of others whose ambitions were thwarted by the country's elaborate testing system, installed by the rulers of a unified China to select officials and fill its gargantuan bureaucracy.

"Some galloped on that path, others faltered and turned to nature for solace," Wang said. "Yet there were others who saw themselves riding a professional and an emotional roller coaster as their fortunes rose and fell, often subjected to factors beyond their own control."

Ensnared by what one famous fourth-century Chinese recluse described as the "dusty net" and buffeted by ever-changing political winds, these scholar-officials developed an even deeper appreciation for a simpler and, ideally, nobler existence.

Nature, which runs parallel to human society, seemed to be able to offer that possibility. "By retreating to nature one declares his intention to live up not to society's expectation but to one's own expectation," Scheier-Dolberg said. "To paint a picture of nature's recluse, or to own one, was almost tantamount to saying that no matter where you were, your mind and your heart belonged to the mountains-moral high ground to which a dignified man must lay claim."

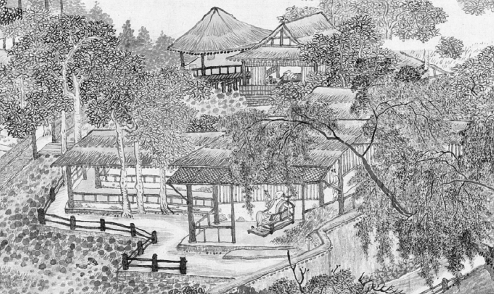

One such person was the 12th-century scholar-official Li Jie, whose hand scroll of an imagined water-facing retirement home is titled Fisherman's Lodge At Mount Xisai. The painting, accompanied by the words of those who felt compelled to put down their thoughts after having studied it, sheds light on a shared dream steeped in idealism. (These words, often themselves masterpieces of calligraphy, are attached to the rear of the painting to form what is known as the colophon.)

"Why fisherman's lodge?" Scheier-Dolberg prompted. "Because a thatched hut, not unlike the wine, had become a symbol for one's dismissal of a regimented, ambition-fueled life and all the luxury that life promised."

Fortunately for Li, his dream was realized around 1184, about 15 years after he enunciated it in painting. So it did for a friend of his named Fan Chengda, a powerful bureaucrat-cum-leading poet who wrote the very first piece of the colophon, which eventually grew so long that someone given the task of mounting the piece felt obliged to split it in two. And in two parts the work is now on view at the museum, quietly taking up the long display cases on both sides of a gallery.

"The length of the colophon testified to the admiration felt for Li by his contemporaries as well as those who came after him," Scheier-Dolberg said. "Spiritually, they aligned themselves with him."

The last one to calligraph the colophon was Ye Gongchuo (1881-1968), a painter and calligrapher who also served as a senior official in charge of transport during China's republican era.

However, the deepest respect has traditionally been reserved for one man, Tao Yuanming, a marvelously endowed writer of poetry and prose who lived between the fourth and fifth centuries, who is revered as "the forefather of all recluses".

"Although he was not the first recluse, he was the first to articulate with such richness that idea of reclusion as a noble way of life," Scheier-Dolberg said. "He made the decision to retire from public service in 405 when he was only 40, and merely two years after he successfully sought a position with a powerful general. Compared with many who spent extended time in office while pining for another, freer life, Tao practiced what he preached, at the peak of his life.

Channeling his energy into drinking, writing and planting chrysanthemums, he created through words a joyous and tantalizing vision of a hermit's life that contrasted with the more brooding and stoic images that also exist in plenitude in Chinese cultural history. (Think about ink-washed paintings of snowy landscape punctuated with the solitary figure of an angler. Wrapped in reed coat and gloom, he is most likely to have turned his back, literally, on viewers and on society.)

Yet it would be naive to think that Tao had not suffered disillusionment. "Realizing there was no way to revive the Jin, all he could do was become 'as drunk as mud'" was the inscription from the 15th-century painter-calligrapher Du Jin, whose portrayal of Tao caught him in a moment of contemplation underneath a giant pine tree, his boy-in-attendance following with a handful of chrysanthemums.

Here, Jin refers to the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420), whose demise was witnessed and lamented by Tao, who, despite his seeming detachment, was not without strong political inclination and a sense of belonging.

With the end of the dynasty, China descended further into political chaos and disintegration. Yet this highly volatile period between the third and sixth century was also marked by flourishing art and literature, which some believe may have been partly fueled by the inner struggle of the disenchanted literati class whose members chose to be recluses in unprecedented numbers.

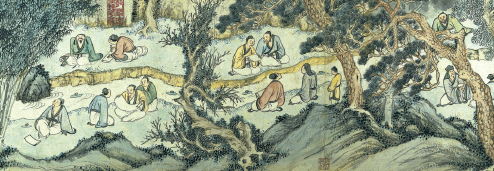

Proving to be immense inspirations, these men and their words found their way into numerous paintings and poetry by later generations. One of them, by the 19th-century painter Liu Yanchong and featuring seven highly adulated writer-hermits from the third century, can be seen at the exhibition.

Known as the "seven sages of the bamboo grove", these men joined Tao in the pantheons of Chinese hermits, due as much to their mutually nurturing friendship as to their literary genius. In what is now Xiuwu county in Henan province, they enjoyed regular get-togethers in the bamboo grove, where they famously let wine and creativity flow freely.

"A hermit is not necessarily a loner," Scheier-Dolberg said. "Communion is not viewed as the opposite of reclusion in premodern China. Rather, the act of separating oneself from society often meant opting out of relationships of necessity and into those with the like-minded, for mutual enjoyment."

Scheier-Dolberg pointed to paintings that show small gatherings, taking place either against a natural background or in what he called carefully curated garden spaces on one's home estate, complete with "cultivated trees and fantastic rocks", all strategically placed to evoke a natural sanctuary and stimulate contemplation.

According to Wang, the limited number of people in those paintings, and the way they were presented-either as pages in booksized painting albums or as long, horizontal scrolls a viewer is expected to open gradually in hand, speaks for the gathering as part of a minority culture.

"The depiction of these events, as the events themselves, were never meant for a crowd," Wang said, pointing to painted home-dividing screens, often seen in ancient Chinese households for the well-off, as examples of popular art.

"The albums and hand scrolls were shared among a knowing audience who saw themselves or their alter egos in them, and were capable of reading between the brushstrokes."

These get-togethers were called elegant gatherings, a term that may sound slightly pretentious. Yet going by what Wang says, the participants had every reason to feel good about themselves.

"Of course they drank wine, played chess, burned incense, spent time looking at some precious old paintings, but the core part of an elegant gathering was composing poetry. Guests were required to write poems based on game rules, to use a specific word or to let the poems rhyme on a certain sound, for example. Failure to do so would probably make one appear less elegant than one had wished to be."

As daunting as that possibility appeared, it turns out that ancient China produced its own bumper crop of talents who reveled in the challenge. Some joined Wang Xizhi, a fourth-century calligrapher and writer of prose, in an elegant gathering he organized, one that has been immortalized by the resulting collection of poems.

During the event, which took place in a scenic spot named Lanting (Orchid Pavilion) in what is now the city of Shaoxing, in Zhejiang province, all 42 participants were seated alongside a winding brook, whose halting flow carried cups of rice wine downstream. Whenever a cup came to a hesitant stop, the nearest person was required to imbibe its contents before coming up with a poem.

Wang, regarded by many of his successors as the greatest Chinese calligrapher of all time, wrote the preface for the poetry collection, a literary and calligraphic masterpiece whose fame grew to such an extent that Li Shimin, a 7th-century emperor of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), was believed to have sought it out and taken it with him into his own burial ground.

Fortunately for modern-day art lovers, copies of the original writing by other hugely talented calligraphers were made before it disappeared.

Then there are the images-numerous paintings made by later generations to help imagine the event, two of which are now on view in the New York exhibition.

"It's important to remember that calligraphy was not born as a blue-blooded form of art," Wang of the Palace Museum said. "People skilled with the use of a brush were once relegated to the role of scribe, with the task of putting down what their superiors had to say, often in official announcements or documents.

"Wang Xizhi was undoubtedly a leading figure in elevating calligraphy to a level worthy of the lifelong trying of a scholar-gentleman. That preface he wrote sealed the deal."

Another, equally far-reaching impact the gathering had was on literati painting, Wang said.

"Writings came first, followed by pictures, since it is words that inform a picture and imbue it with meaning. This is something that is distinctly Chinese, something that sets the tradition of Chinese literati painting apart from all the other great painting traditions of the world."

Wang once studied Chinese art history at Beijing Normal University. Among his teachers was the renowned contemporary calligrapher Qi Gong (1912-2005), a descendant of the ruling Aisin-Gioro family of Qing (1644-1911), China's last feudal dynasty.

"One story he was fond of telling was of when he, as a young man, took his own paintings to a senior family member and painting master for advice. The old gentleman asked a single question before agreeing to open the scroll: 'Does it have a poem?'," Wang said.

"What he meant was that a painting not made by a literary-minded man was decidedly second-rate. In other words, throughout its history, a piece of literati painting was often judged not so much on the merits of its brushstrokes as on its import."

Although literati painting came into being only in the eighth and ninth centuries-before that the scene was dominated by professional painters who were skilled artisans with little formal education-it was able to draw from the immense cultural and spiritual legacies of the previous centuries, to which both Wang Xizhi and Tao Yuanming were contributors.

Having died in 361, four years before Tao was born, Wang Xizhi was spared the demise of the Eastern Jin Dynasty in 420. This is particularly important because the calligrapher came from the powerful Wang family that helped shape the dynasty's politics.

Wang Xizhi was born with a silver spoon in his mouth and never felt the need to worry about the more mundane matters in life; but there were others who had to toil to make ends meet while finding time to entertain their vision as a noble-minded recluse.

Shitao (original name: Zhu Ruoji), a much-revered 17th-century painter-recluse whose painting album is on display in the exhibition, complained later in life to a friend about having to labor on a commission of large-scale screens meant as home decor.

Talking of reality, in premodern China one group bound by reality to live rather secluded lives were women. Scheier-Dolberg gives space to that aspect by including images of aristocratic ladies seen in residential spaces, "heavily manicured" gardens, for example.

In 1799 a female scholar named Cao Zhenxiu wrote a cycle of 16 poems-all on famous women of history and legend-before commissioning a young painting virtuoso of her time, a man named Gaiqi, to provide illustrations. The result, on view in the exhibition, shed light on what Scheier-Dolberg called "an increasing participation of women in literary activities", exemplified by Cao, who, judging by the poems, clearly felt an affinity with her female predecessors in history.

Among them was Madam Wei Shuo, a maternal aunt of Wang Xizhi, who first taught him calligraphy.

The exhibition also features images of women enjoying their own elegant gatherings. Throughout premodern Chinese history such events largely existed in paintings or book pages, that is in the imagination of artists and writers, Wang Yimin said. This is not to include the get-togethers of wives and concubines of a powerful patriarch, which, by virtue of all the chess-playing, tea-savoring and string-plucking, resembled an elegant gathering.

"Even during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), a period characterized by a prosperous, open society, women were only allowed to attend gatherings accompanying their husbands," he said.

Although small in number, literally accomplished courtesans offered the most notable exceptions. Turning up at an elegant gathering not as the accessories of men, but as their counterparts-at least creatively, they left behind words that lasted as long as their legends.

Within that painting album by Shitao are two images of fishermen. Their existence, with that of the woodcutters, was long romanticized by the members of the literati class. Tempted to think that they might one day trade their living "at the whim of a massive bureaucracy", to quote Scheier-Dolberg, for one at the whim of nature, the scholars-officials embraced these men of hard labor as they did Tao Yuanming's chrysanthemums and thatched huts.

Sometimes just a fish might do. In 1082 the Song Dynasty (960-1279) literary giant Su Shi, after discovering that he still had wine and fish to offer, embarked on a nighttime escapade with friends. A more adventurous version of the elegant gathering, during which Su climbed to the top of a cliff to release a "primal scream", the event was recorded by Su in his literary masterpiece Second Ode on Red Cliff.

Throughout his life, Su repeatedly found himself at odds with those in power and went into exile several times, including to Huangzhou, Hubei province, between 1080 and 1086, where Red Cliff is located. The free-spirited sublimity of his words hardly belies the poverty he was then subjected to, as the scourge he endured did little to diminish his concern for the masses or make him cynical.

"One did not have to go into the mountains to embrace nobleness, which is closely tied to the Chinese perception of a recluse," Wang said. "It's more about a state of mind that the Chinese literati had been aspiring to for 2,000 years."

It is no accident that within 50 years of Su's death in 1101, the reigning Song Dynasty emperor Zhao Gou transcribed his piece in the emperor's own cursive handwriting and attached it to the rear of a hand scroll painting he commissioned from one of his court painters depicting the outing. The piece is held by the Palace Museum in Beijing. Two other pictorial renditions of the same event are on display in the New York exhibition.

"Judging by all standards, an emperor is the opposite of a recluse who relinquishes social wealth and ambition, but that didn't stop Zhao Gou or his successors from putting themselves in the mind of those who did so, or presenting themselves as one of them," Wang said, referring to a painting housed by the Palace Museum in which the 18th-century Manchu Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was seen as a plain-robed scholar-recluse, waited on by an attendant boy instead of his court.

Communion was what the emperor was hoping for-communion with the educated members of his empire.

The fishermen under Shitao's brush are anglers to be exact, one of whom was sitting on a bridge, pole in hand. "The painter had clearly projected himself onto this image of the angler who, as imperturbable as the water surrounding him, doesn't seem to really care much about what he's doing," Scheier-Dolberg said.

"You must know that he who casts a fishing line is not someone who desires fish," wrote Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), an iconic figure in Chinese art history, in a poem accompanying his painterly depiction of a famous scholar's garden that still exists today in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. The painting is on view in the New York exhibition.

Wen, who lived the last 33 years of his 89 years in relative seclusion, was probably referring to self-cultivation. But those who were lucky enough to hold the painting and gaze at it may have had something else in mind. One of them was Yixin, the powerful regent Prince Gong of the ruling Aisin Gioro family of the Qing Dynasty, who literally sealed the painting with his royal stamp of approval.

Born in 1833, when the fortunes of the empire were on the wane, he spent a good part of his life trying to turn it around, by repairing a weakened government, adopting military reform and effecting a rapprochement with the foreign powers who were pounding on China's door with cannonballs. Nothing really worked. He died in 1898, 12 years before the collapse of Qing, thus saving himself the suffering that China was subjected to in the following decades.

He was not alone. The exhibition has a 15th-century calligraphy piece that features a renowned prose poem from the third-century BC. Written as a series of exchanges between the author Song Yu and the ruler of the Kingdom of Chu during the Warring States Period, it employs angling as a potent metaphor for statecraft.

Not unlike those itinerant scholar-lobbyists of his time, the highborn Song Yu tried to influence the rulers and had his share of triumph and defeat before dying at the age of 67 in 223 BC, the same year the Kingdom of Chu was destroyed by the Kingdom of Qin in its effort to unify China through military campaigns, which it did two years later in 221 BC.

"If a ruler uses saintly behavior as the pole, high morals as the line, deep humanity as the hook and bountiful wealth as the bait," Song's prose poem said, "then the world will be his pond and the populace his fish."

Today's Top News

- Xinjiang harnessing clean energy for a better future

- Melodies of belonging and shared heritage echo across Strait

- China all set to safeguard trade interests

- Celebrations inspire unity, confidence

- Xi sends congratulations to Malawian president-elect

- Premier calls for efforts to enhance China-US ties