A DIAMOND HEWN OUT OF THE SNOW

A chance meeting in New Hampshire between E. Grey Dimond, a cardiologist, and his famous contemporary Edgar Snow led to a friendship that long outlasted the latter's life, and a quest by the former to get close to a country Snow had sought to understand and to explain.

On Sept 15, 1971, E. Grey Dimond, 53, found himself crossing the border between Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland, from what he called "neon China" to New China, half a year before US president Richard Nixon stepped onto the ground at the airport in Beijing to begin what he called his "week that changed the world".

The cardiologist, today remembered as the founder of the School of Medicine at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, had a special mission on that trip. He was to verify some reports filed by his fellow Kansas City native Edgar Snow, based on the man's own previous travel to China during which he was invited to ascend the rostrum in Tian'anmen Square at a time when the US and China were estranged.

"This chance to review patients, their records, their medication …from this experience I realized that Edgar Snow has been right (in noticing the huge advances made in Chinese medicine)," wrote Dimond in his 1975 book More than Herbs and Acupuncture, countering the prevalent view in the West.

"I enjoy the criticisms of contemporaries who are so buried in their hostility toward that they could not see the 'return' of China," Dimond said.

One of the best-known victims of that hostility was Snow.

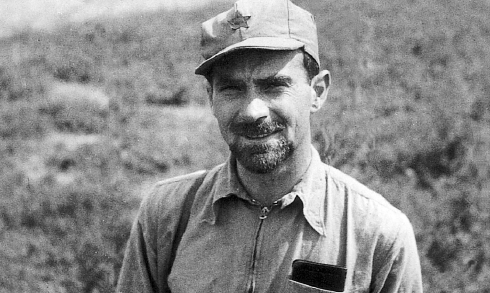

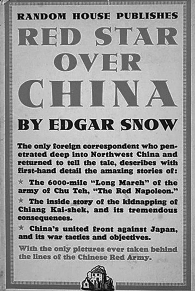

Between June and October 1936, Snow, after having studied journalism at the University of Missouri and spent eight years in China, traversed hundreds of miles of inhospitable territory to reach the Chinese Red Army base in the country's northwest, where he listened, observed and reported the Communist revolutionaries' own stories in their own words. More than 100,000 copies of the resulting book, Red Star Over China, sold in England alone within its first few weeks of publication.

It was instantly considered a classic and remained so, for "this book has stood the test of time on both these counts-as a historical record and as an indication of a trend", to quote the celebrated China scholar John K. Fairbank.

That "trend" has since captured the fascination of the West. But it also led, during the era of McCarthyism, to Snow's exile in 1959 from the US to Switzerland, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Yet Snow, who remained a US citizen throughout, did return on rare occasions, including in October 1965, when he was in Dublin, New Hampshire, for the Dublin Peace Conference. It was organized by Grenville Clark (1882-1967), an influential lawyer of his time and author of World Peace Through World Law, who was nominated four times for the Nobel Peace Prize.

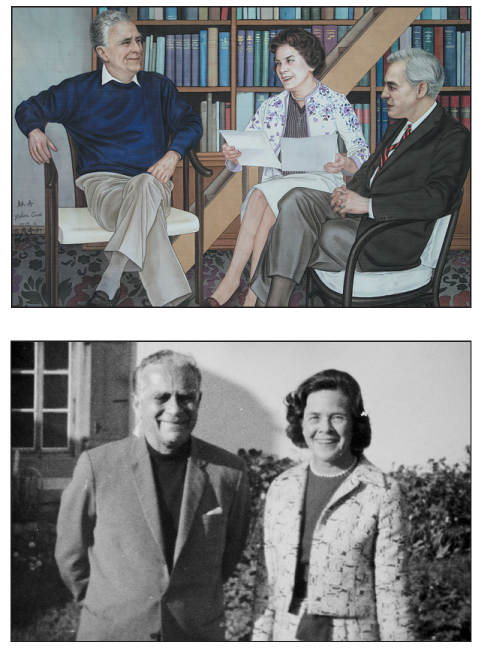

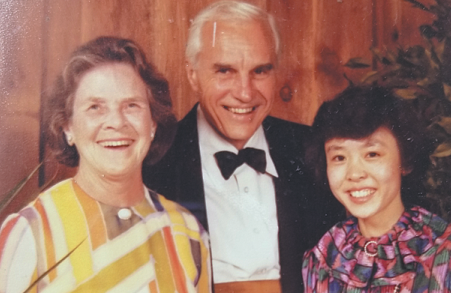

"The participants … were stimulating, but the man who brought real excitement to the gathering was the expatriate American author Edgar Snow," Dimond, who married Clark's daughter Mary Clark, and was at the conference, later wrote.

"In Dublin, Edgar Snow and Dr. Dimond shared adjoining rooms with a bathroom-proof of a very special kind of friendship," said Nancy Hill, Dimond's personal assistant for the last decade of his life. The two men really hit it off, with Snow introducing Dimond to the term Third World and its vast potential implications.

"Snow was saying: You guys thinking in your Western-versus-Soviet communist way leaves out one fourth of the population on Earth. There's this whole other population that is neither Soviet nor Western, who are suffering through the remnants of imperialism, who want more freedom and revolution in some cases, and who don't want to be told by you guys that they should preserve what they have through your legal traditions.

"This provided Dr. Dimond with his 'light bulb' moment."

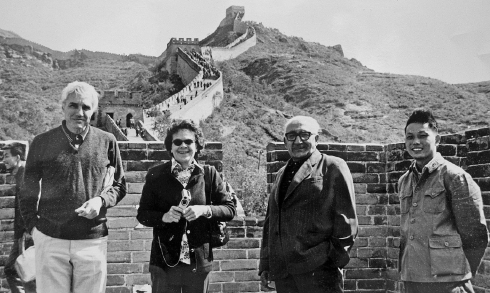

Then came Dimond's China trip in 1971, during which he was joined by his wife Mary and three of his fellow doctors, including his 85-year-old teacher Paul Dudley White (1886-1973), a cardiologist who had served as president Dwight D. Eisenhower's physician. No other American doctor had visited China since 1949.

The trip was only possible because of Snow, who wrote directly to the then Chinese premier Zhou Enlai on behalf of the prospective visitors. In 1936, upon Snow's arrival at the Communist base in Bao'an, Shaanxi province, Zhou surprised him by talking to him in English. In his 1968 documentary The China Story: One-Fourth of Humanity, Snow narrated rare footage of his meeting with Zhou, atop a horse with a "pre-Castro beard", a style Snow himself soon took up during his stay there. (Dimond's father-in-law, to whom Snow dedicated his 1968 edition, the final one, of Red Star Over China, funded the film.)

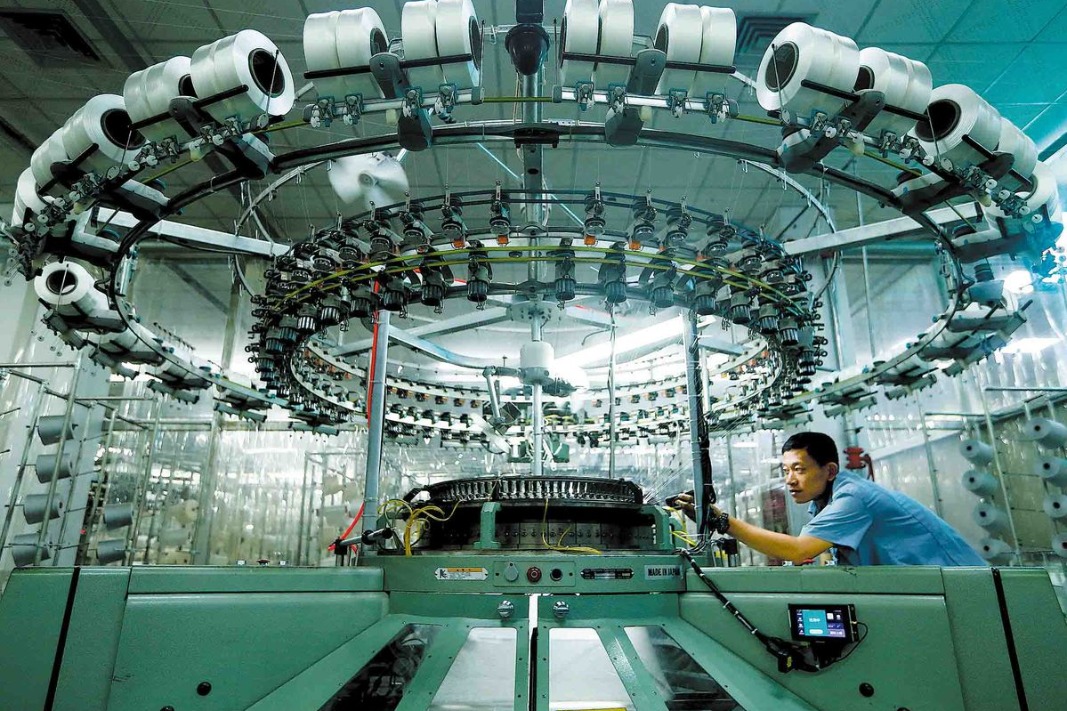

Dimond died in 2013, having made about 40 trips to China and enabling two-way exchanges from academia to the arts, from culture to commerce. Somewhere among those trips he visited the caves carved out of the vertical faces of the yellow-earth plateau in Bao'an. There Snow sat down for days in 1936 with the young Mao Zedong who was virtually unknown in the West, before leaving to write the world's first detailed portrait of a man who later became the founding chairman of the People's Republic of China.

"By dedicating the rest of their lives to the country Snow had introduced to them, the Dimonds were able to develop a deeper connection with the journalist long after his death," Hill said.

In fact, en route to Hong Kong during their 1971 trip, the Dimonds stopped over to see Snow at his home in Eysins, Switzerland, and to go through his multiday "intensive course on modern China", accompanied on its last night by Moutai, a Chinese drink "to be respected" thanks to its high level of alcohol.

"I … said to Edgar that I did not understand what he meant by Marxist principles, and I didn't understand what he meant by Mao Tsetung (Mao Zedong) Thought,"Dimond later wrote in his book. "Edgar laughed, raised his thimble of Moutai, and said,"Here's to your China education. Ganbei! (Bottoms up)"

In Beijing in 1971 the Dimonds visited historical sites, ate Peking duck and struggled to develop further appreciation for the reputed Moutai. But a particularly meaningful moment came when Dimond observed his Chinese counterparts performing surgery under acupuncture anesthesia.

"Dr. Dimond first became interested in acupuncture in Vietnam in the 1960s, when he was sent there during the height of the Vietnam War," Hill said. "The preparation he was given for his lecture in Hanoi was centered on what one should do if a bomb went off."

What he probably had not imagined then was that years later an effort by president Richard Nixon to end that same war-an effort for which Nixon was seeking China's help-contributed to a thaw of Sino-US relations, and to Snow's return to the spotlight, after his virtual absence from public view in the US for nearly 20 years.

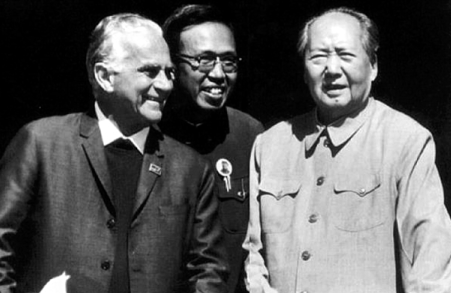

During his last visit to China, between August 1970 and February 1971, Snow had not only got glimpses of China's massive educational program in family planning and birth control, but also climbed atop the Tian'anmen rostrum to watch-side by side with Mao-the parade that was taking place on October 1, China's national day.

Carried by newspapers worldwide, "the picture of the two … told the whole world and the Chinese people that we are friendly to the American people," said Ji Chaozhu (1929-2020), Mao's English interpreter and author of the memoir The Man on Mao's Right, in an interview in the 2000s. "And if the American administration has a similar idea as the American people… we are ready to establish a good relationship, working relationship with them."

Two months after the Tian'anmen parade, Snow sat down with Mao in his study for "a five-hour discourse", to use Snow's words, in which Mao said he would be happy to talk with Nixon "either as a tourist or as president". The message was first announced in the article Snow wrote and published in Life magazine on April 30, 1971.

And it seemed to have set in motion a chain of events: between July 9 and 11 that year, Henry Kissinger, Nixon's security adviser, secretly traveled to Beijing to negotiate on a possible visit by Nixon; on July 15 Nixon shocked the world by announcing on live television that he would visit the People's Republic of China the following year, which he did from February 21 to 28, 1972.

Amid all the excitement surrounding the rapprochement, very few in the US were aware of the fact that Snow, whom Life said "probably has more firsthand information than any American … on what the Chinese leaders think about the US today", died of pancreatic cancer on Feb 15, 1972, at the age of 67.

Dimond was among those who were first informed when Snow was diagnosed with cancer in late 1971, barely three months after the doctor returned from his own China trip.

"I called Dr. Ma Hai-the (Ma Haide) in Peking," wrote Dimond in his 1975 book.

Ma Haide is the Chinese name of George Hatem, a Lebanese-American doctor who joined Snow on his adventure to seek out and speak to the "Reds" in 1936. Hatem stayed on in China and became a Chinese citizen.

It did not take long before Hatem, with his team of Chinese doctors, nurses, nutritionist and even a chef, flew in from Beijing to Geneva at the behest of Mao and Zhou. Taking up residence at Snow's place they tried everything within their capacity to enable Snow to "die gently", as Dimond put it.

Another old friend who went to Snow's bedside was Huang Hua, then China's first permanent representative to the United Nations. Huang, a student revolutionary and close friend of Edgar Snow in Beijing in the 1930s, caught up with Snow in Bao'an in 1936 and accompanied him further west at the end of his five-month stay there, acting as his interpreter.

"The three red bandits" was how Snow referred to Hatem, Huang and himself, Dimond said. This was even though Snow had, in his own words, "never been a member of the Communist Party".

"This book (Red Star Over China) predicted that the communists would win victory. It was, however, not a book of advocacy. It was a book of reporting," wrote Snow in the 50s, when letters to him from China were delivered having been opened, presumably by the FBI, and he felt more than ever before the need to defend himself.

One person who was trying to correct the wrongs was Dimond, who wrote to Nixon when Snow's cancer was first found, seeking medical help.

"I elaborated in telephone calls to the White House, here was a remarkable opportunity to show the world the errors of the tragic policy of previous years which had scarred the careers and spirits of honest men, such as Snow," wrote Dimond in a chapter of his 1975 book titled Journey To The Beginning, a nod to Snow's autobiography of the same name.

"The final White House response to me, by telephone, was to thank me for my concern and to advise me that the president could not make special exceptions. … After all, there were many Americans living overseas."

While Snow's memorial was held in Geneva on Feb 19, 1972, Nixon was en route to China, almost everyone within his entourage carrying a copy of Red Star Over China.

"It's hard to see justice in such timing," a deeply saddened Dimond said. "The journalist who has tried to tell his country its Asian policy was wrong, and who had brought personally from Mao Tse-tung the clear signal that Mr. Nixon would be welcome in Peking, left the scene just as American Asian policy made the giant turn away from the issues that had made enemies of the two nations."

The doctor and his wife, who also attended the memorial, found their consolation two years later with the establishment of the Edgar Snow Memorial Foundation, the first of its kind anywhere.

"It's a project that got almost unanimous support from people who knew Edgar Snow, including Huang Hua, who came to be a close collaborator to the Dimonds on their work,"Hill said.

Yet their work began even before that. In November 1972, nine months after the Nixon visit, Dimond helped bring to the US the first delegation of Chinese physicians since 1949.

On Jan 31, 1979, the Dimonds were at the Chinese Liaison Office in Washington being received by the then Chinese vice-premier Deng Xiaoping during his state visit to the US following the official establishment of Sino-US diplomatic relations earlier that year.

"We remembered Grenville Clark, Paul White, and Edgar Snow, and wished they were with us on this evening," Dimond later wrote.

Yet the memory of Snow came most powerfully to Dimond through the doctor's association with his friends, people with whom Snow had been brought together during his stay in China between 1928 and 1941, by both destiny and a shared desire for truth and the betterment of human conditions.

Two people on this list were George Hatem and the New Zealander Rewi Alley. Not unlike Snow, both had an intrepid heart that led them to Shanghai in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Both became disillusioned and disgusted by what they saw in the hedonistic "Pearl of the Orient": the seemingly endless dying of the poor and the execution by the ruling Nationalist government of those who were "trying to agitate against this sort of thing", to use Hatem's words. Both reached out to the leftist thinkers and writers around them, both Chinese and non-Chinese, and soon developed a strong curiosity and sympathy toward the Chinese Communists.

"When word came from Rewi Alley that the Red Army needed a Western-trained doctor, I was delighted, "recalled Hatem, who came to China as a medical student intent on studying tropical diseases, many years later.

From Shanghai Hatem embarked on his own separate journey toward the "Red Zone", one that intersected with Snow's when the two arrived at Zhengzhou in Central China, a major railroad junction. They completed the rest of their journey together, winning each other's trust as they tried successfully to slip through the military blockade of the Nationalists, at risk to their own lives.

As Snow left at the end of his five-month stay to work on his "scoop of the century", Hatem stayed, became a Red Army doctor and married a Chinese woman. By the time Dimond met him for the first time in 1971, equipped with a letter of introduction from Snow, Hatem had become known as the man responsible for ridding China of venereal diseases, or simply the most famous American living in China.

In April 1978, at the arrangement of Dimond, the "Dr. Horse of China" as Dimond called Hatem, made his first visit in 50 years to his native United States. (Hatem's Chinese surname Ma could also mean horse.)

The sentimental journey took him to his hometown in Buffalo, New York, where, when asked if he thought China was the best of all worlds, he replied,"China is the best for China." He later delivered a speech before the United States-China People's Friendship Association in San Francisco.

"It was a mellow time, a time for reflection, comparison, mending ties, a time needed to complete one's life cycle," Dimond wrote in his 1983 book Inside China Today, one filled with his long conversations with Hatem.

Some of those conversations were joined by Alley, whose Beijing home Dimond had tried unsuccessfully to locate during his first trip there, with a hand-drawn map from Snow.

In 1939, two years after Red Star Over China was published, Snow returned to Shaanxi to report on a burgeoning form of mobile, small-scale production units known as Gung Ho, or industrial cooperatives. Set up everywhere, including in cave dwellings, they had the unique advantage of escaping Japanese bombing, while providing desperately needed wartime materials for frontline soldiers and jobs for the millions of refugees who had trekked west.

The idea was mainly that of Alley, who oversaw its implementation and is known today as "the father of Gung Ho".

Dubbing it "guerrilla industry",Snow not only contributed to the very idea of Gung Ho, but was also actively involved in it.

While the Alley in Snow's 1958 autobiography Journey to the Beginning was a "red-haired, broad-chested, driving man with legs like tree trunks", the Alley Dimond came to know in the 70s and 80s was "pink-haired, mellow, moves with unshakable calm and speaks in slow, careful cadence".

"(Hatem and Alley) walking arm in arm, very slowly, heads together, chatting away like two upright bears" was one soothing picture Dimond painted. Between them, Hatem and Alley filled for Dimond more than a few narrative gaps in Snow's life journey, while having their own remarkable journeys witnessed by a man infinitely inspired by their long-gone friend.

Both Hatem and Alley died in the late 1980s, deeply mourned by Dimond. But more devastating was the sudden loss of his wife five years earlier. On June 8, 1983, after organizing and hosting the first edition of the Edgar Snow Symposium, Mary Dimond, president of the Edgar Snow Memorial Foundation, died in her sleep from a heart attack, at the age of 67. The couple had planned to divide their time between their home in Kansas City and a ranch in California.

The grieving, done by Dimond in private, was not lost on Wu Tong, daughter of Dr. Wu Weiran, who was among the first to meet Dimond when he arrived in China in 1971 and who headed the Chinese physicians' delegation to the US in 1972. Coming to the US in 1980 to study at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, which Dimond founded, Wu Tong became the couple's adopted daughter and stayed with them at their home for more than two years.

"In my first year in the States, every night after dinner, Mary would spend an hour practicing English with me," recalled Wu Tong, an eye doctor in her 60s.

"Together they had been to many places in China, had lived in tents in areas where there was no running water. They never complained-in fact, they savored every moment of it," said Wu. "I remember stealing a glimpse of Dr. Dimond in his study, not long after Mary's passing. He was just sitting there, in a trance, which is very untypical of him."

"I let my life sleep for a while, mulled, thought, weighed," Dimond wrote. "I decided to stay put at 25th and Holmes (the couple's Kansas City home address) and wave the flag more vigorously, permanently."

Dimond later took on the presidency of the foundation and continued the biennial symposium, which, with the participation of Huang and his successors, has been taking place alternatively in Kansas City and in China.

Because of the pandemic the 19th Edgar Snow Symposium in Beijing next month will be held as an online event.

"When the official channels of diplomacy become obstructed by clamor and conflict, the work of international friendship and interpersonal communication can help to bridge the gap of intercultural perceptions and keep the conversation moving forward in a positive direction," said James McKusick, the foundation's former president, referring to the current poor state of the relationship between China and the US.

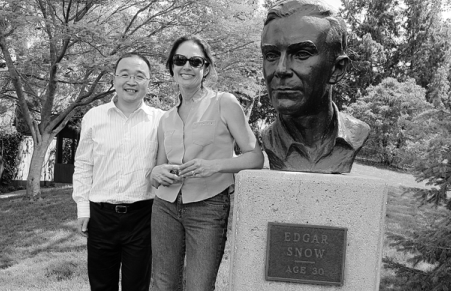

One person who is behind this year's event is Sun Hua, director of Peking University's China Center for Edgar Snow Studies. "The center was established in 1993 at the initiation of Huang Hua, who served as its honorary director before his own passing in 2010," Sun said. "Why Peking University? Because this is where Snow is buried, in China."

In a note that Snow wrote, and which his wife Lois Wheeler (1920-2018) discovered in the days after he died, he said: "Someone please scatter some of my ashes over the city of Peking, and say that I loved China. I should like part of me to stay there after death as it always did during life." (Snow married Wheeler in 1949, after his divorce from Helen Foster, whom he had married in 1932.)

The wish was fulfilled on October 19, 1973, as Wheeler, escorted by Hatem, arrived on the campus of Peking University for the burial of half of Snow's ashes, in a ceremony attended by premier Zhou. It was on that campus that Snow taught journalism in the 1930s, with Huang among his students.

Snow's note also said:"America fostered and nourished me. I should like part of the same residue scattered over the Hudson River, to join other debris which touches our shores."

Dimond took part in carrying out that part of the wish with the Snow family at Sneden's Landing in upstate New York, near the Hudson River.

Wheeler later gave a large collection of Snow's papers, pictures, film footage and memorabilia to the University of Missouri-Kansas City, with which the Edgar Snow Foundation is affiliated.

In the summer of 2012 Sun visited Dimond at this Kansas City home for the first time. There, in a redwood building on the university campus he discovered what Dimond must have discovered at Hatem's living room in Beijing:"Pure USA with a Chinese heart", as Dimond put it. With memorabilia from all his China trips artfully on display, the space had been turned into a scholars' center, dedicated to things in which "we both, Mary and Grey, have a faith"-"human dialogue, social intercourse, the amenities of scholarly communication."

Walking around the 3-acre oasis with Asian-garden inspired grounds, Sun saw beautiful little gravestones with Chinese characters on them. "It turned out that Dimond had given his pet dogs highly entertaining Chinese names,"Ma ma hu hu, meaning so-so, for example," Sun said.

By the time of Sun's visit, Dimond had stopped traveling to China because of the infirmities of age. But before that he had passed on his passion for China to many around him, including Hill.

Following in the footsteps of Snow and Dimond, Hill found herself in the cave dwellings once inhabited by the "Red Bandits", "storied, magical" places where "time seems to have slowed down", she said.

"Dr. Dimond always said that there's this natural harmony between Americans and Chinese-both are secular, fun-loving people endowed with the same sense of humor," said Hill, who joined the foundation's board in 2012, after her first trip to China, where "the Snow legacy feels so much more real and present".

Sun returned to visit Dimond in May 2013, six months before the old man's passing in November. Upon Dimond's request, Sun arranged for a reprinting in Beijing of 200 copies of his Inside China Today, a book he dedicated "to Edgar Snow, George Hatem, Huang Hua and to their adventure of 1936".

"The very nature of journalism has changed in the West (since Snow's time) … With a terrible dearth of independent Western reporters working in places like China, the inevitable outcome is that news from those parts of the world will be reported at second or third hand, with a lot of unconscious bias or even intentional 'slant' injected into the story," McKusick said.

"The world needs more fearless independent foreign correspondents like Edgar Snow who are willing to go the extra mile to find the truth and report the real story."

On the morning of Nov 3, 2013, Dimond talked on the phone with Wu Tong, who was made the executor of his estate even though he had three biological daughters in the US. In the evening that same day, the 94-year-old cardiologist who loved woodcarving died peacefully at his home, a place he named Diastole.

"Diastole is a word with a bit of music and poetry in it," Dimond wrote in his book Distant Milepost. "Diastole: when the heart rests."

Sun said from Peking University:"He proved with the latter half of his life how a venerated doctor can use his or her professional and social stature to break ideological barriers and do cultural cross-pollination. In that sense he set a precedent that hasn't gone unnoticed."

Hill, referring to Dimond's attitudes toward both acupuncture and Chinese socialism said it was about "respecting alternative systems".

"Be modest in your conclusion," he wrote toward the end of Inside China Today. "Leave room for change. Above all, weigh what you are seeing against the past-against the future-and against the success and flaws of our own society."

It is a heartfelt humbleness Dimond inherited from Snow, who, on arriving in Shanghai in 1928, decided to stay there and "save the rest of the world", because "China was a world in itself".

In 1946, after World War II, a 28-year-old Dimond was sent to Tokyo to treat Americans who were former Japanese prisoners of war. There he met J. B. Powell, who, by virtue of being a Missouri School of Journalism graduate and an editor of the China Weekly Review in Shanghai in the 1930s, was a close associate of Snow, who regularly contributed to the English periodical.

"Dr. Dimond at the time had already heard about Snow," said Hill, today the honorary president of the Edgar Snow Memorial Foundation. "And J. B. Powell undoubtedly filled him with more details of the man. But it wasn't until he met Snow in 1965 that he realized why he was such a successful journalist.

"Snow was smart, engaging, genial and warm. He was a guy who was in the moment, who cared so deeply about who he was talking to and what they were talking about. When the two were conversing, the rest of the world just went away."

Asked about Snow's most important advice to Dimond, Hill replied:"You have to be in China to understand it."

Today's Top News

- China, US announce measures to ease tariff tensions

- China releases white paper on national security

- Marriage reforms making it easier to tie the knot

- Nations vow to uphold intl justice

- Head-of-state guidance key for Sino-Russian ties

- China-CELAC Forum to send unity message