How plowshare diplomacy won the day

Charles Freeman watched through the window of Air Force One when president Richard Nixon walked down the air stairs extending his hand to Chinese premier Zhou Enlai on Feb 21, 1972. Best known in China today as the chief US interpreter on Nixon's historic trip, the veteran diplomat recalls the crucial moment, and the shaping of Sino-US relations in their most 'malleable and creative' years.

In April 1971 a young government official, Charles Freeman, returned to his post at the US State Department in Washington after spending two and half years studying Chinese in Taiwan. He then "started writing papers for an unknown purpose", to quote the 78-year-old.

"An unknown purpose" may not be quite accurate, since Freeman was able to do his own guesswork based on what he was asked to write about.

"What is China's position on this and that? Why does China take this position? If this comes up in discussion, what is our position and how should we explain it to the Chinese? Those were the sorts of things I needed to prepare," Freeman says."There were also the background papers-a lot of information about different aspects of Chinese culture, history and so forth. And most importantly, the Taiwan question."

Any doubt that Freeman had had was dispelled as president Richard Nixon spoke to Americans from an NBC television studio in Burbank, California, on July 15, 1971, announcing his decision to visit China at "an appropriate date before May 1972".

Nixon also acknowledged a secret meeting between Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser, and Chinese premier Zhou Enlai barely a week earlier, from July 9 to 11, a meeting in Beijing that Kissinger had flown to from Pakistan to take part in, after feigning stomachache in Islamabad.

For the ensuing six months Freeman, the self-professed "worker bee", and his colleagues on the China Working Group were "locked up" in what was known as "the op-center", where they were "insulated from everybody" during "a time of obsessive involvement" in preparing for Nixon's impending trip to China.

"The purpose was to maintain secrecy," said Freeman, who then had no idea that despite a lustrous diplomatic career that would follow, he would be most remembered, up to this point, as the chief US interpreter on Nixon's China trip.

In fact, he was not even sure that he would be on it, not before he received baggage tags from those organizing the trip. According to Freeman, before the trip, Nixon, wanting to read up more on China, borrowed from him "quite a collection of books that I had accumulated" but "never returned them".

As Nixon and his 350-strong entourage including media left Guam International Airport for Shanghai on Feb 21, 1972, Freeman was on the backup plane feeling the "apprehension" around him. He switched to Air Force One later that day, and watched out of the window as Nixon and his wife Pat descended from the plane to the ground at the old Capital Airport in Beijing, the president famously extending his hand toward the Chinese premier, waiting for him.

"We were asked to get off the plane later so that members of the press, most of whom arrived with the backup plane half an hour earlier to get themselves in position, would get the best pictures the president wanted them to have," Freeman said.

Efforts to enable "the best pictures" including dressing Mrs Nixon in red, something Freeman advised against on the grounds of its wedding-ceremony connotations in Chinese culture, but it turned out to be a deft PR stroke. Yet when it came to making visual impact on the millions of television viewers in the US, nothing was as symbolic and powerful as that handshake.

Nixon recounted the moment in his memoir. "Chou (Zhou) En-lai stood at the foot of the ramp, hatless in the cold. Even a heavy overcoat did not hide the thinness of his frail body. When we were about halfway down the steps, he began to clap. I paused for a moment and then returned the gesture, according to the Chinese custom," Nixon wrote."When our hands met, one era ended and another began."

Nixon, whom Freeman described as "a very intelligent man and a strong advocate for whatever view he had", was also fully aware of the risky nature of his undertaking in terms of domestic politics, according to his interpreter.

"These days, some people are of the opinion that Nixon went to China to bolster his domestic political standing. I found that incredible because those of us on the trip had no idea that the trip would be so favorably received. It was a big gamble-Nixon was planning to run for reelection. If this had gone badly he would have failed."

That said, Freeman admitted that to arrange for the US"an honorable exit" from the war in Vietnam topped Nixon's agenda."It was surprising and very fortunate that the American public understood the strategic importance of what Nixon was doing, and the bravery it involved."

"Bravery" also due to the mounting pressure from "friends and allies", among them Japan and the Nationalist government in Taiwan, said Freeman, who soon found out that he and the other two people on Nixon's interpreting team made up "an odd group".

"One of them was rabidly pro-Kuomintang (the Chinese Nationalist Party)-he went off on a hunting trip in Taiwan with Chiang Ching-kuo right after the trip. The other was a 'Taiwan-independence' advocate. (Chiang Chingkuo was the eldest son of the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan.)

"They were brought in as my backup and were never used for interpreting," says Freeman, who, to his own surprise, saw himself refusing to interpret for the president the first time he was asked to do so, one and a half hours before the Nixons attended the welcoming evening banquet at the Great Hall of the People, where they were guests of Zhou.

"I was called over to the president's villa and was told by Dwight Chapin, acting chief of protocol for the trip, that the president would like me to interpret the banquet toast," he said.

Having done the first draft for the toast and knowing that his original version had been altered with the insertion of some English translations of chairman Mao Zedong's poems, Freeman asked for the text and was bluntly told that there was no text.

He then confronted Chapin with the truth. "If you think I'm going to get up in front of the entire Chinese politburo and ad lib Chairman Mao's poetry back into Chinese, you're nuts," he told Chapin, whom he called Nixon's "gate-keeper".

At that point, Chapin said "all right". He then "took the text out of his pocket and gave it to the Chinese", who later did the interpretation, according to Freeman. After the trip, Freeman learned that it was Richard Solomon, a member of the US National Security Council, who struck in the lines "to ingratiate the president with the Chinese leadership". Solomon played a pivotal role when the Chinese table tennis team visited the US in April 1972, barely two months after Nixon's trip to China.

In retrospect, Freeman considers the episode a pointed example of the extraordinary measures the Nixon administration had taken to maintain secrecy, without which "the trip wouldn't have been possible", given the domestic opposition he might have faced.

"Nixon had a predilection for using the other side's interpreters, because they wouldn't leak to the US press and Congress," Freeman says.

It is also worth noting that on the afternoon of the same day, Nixon met Mao at his residence for an hour. That was not on the day's schedule, and Nixon, who was given short notice, took along with him only Kissinger and Winston Lord, Kissinger's special assistant, who became ambassador to China between 1985 and 1989.

"The reason (for the sudden meeting) was because Mao was in very frail health at the time," said Freeman who, like the rest of the entourage except for Kissinger and Lord, did not get the opportunity to see the Chinese leader.

His memories of his encounters with some Chinese officials and diplomats have endured. At some point on the trip he was offered a cigarette by Li Xiannian, who became Chinese president in 1983. "I had given it up nine years before, when I was in law school in the early '60s. But I took it and have smoked ever since," Freeman says.

Days later on the plane from Beijing to Hangzhou, Freeman had a long conversation with Zhang Wenjin, who served as China's ambassador to the US between 1983 and 1985. In July 1971 Zhang and the other three were in Islamabad to meet Kissinger before they all flew to Beijing on a Pakistani plane.

Then there was Zhou, who had charmed more than a few of his foes and fellow negotiators over the decades."I remember a remark that Dag Hammarskjold (United Nations secretary-general from 1953 to 1961) had made, to the effect that, when he first met Zhou Enlai, as he did, I believe, during the effort to compose a truce in Korea, for the first time in his life he felt uncivilized in the presence of a civilized man," said Freeman, when he was interviewed for the oral history project of the Library of Congress in Washington in 1995.

Speaking to the young man across the dinner table on several occasions, Zhou asked Freeman about his background and Chinese-learning experience. On the group's last day in Beijing, Zhou, apparently having been briefed by his staff on Freeman's search for a set of Chinese history books in one of Beijing's biggest bookstores at the time, told him that he was going to give two sets of the original 18th century edition of these books to the United States.

One of the two sets, which Zhou presented through Freeman, is now in the State Department Library.

With his Chinese counterparts interpreting for Nixon and Zhou, Freeman did interpretation almost exclusively at the foreign minister level, where "all the shouting and screaming" (his words) took place.

"The US secretary of state William Rogers and the Chinese acting foreign minister Ji Pengfei discussed issues including Korea, Vietnam, Kashmir and Japan's role in the region," Freeman said. "We almost couldn't agree about anything except that China and the US should work towards normalizing relations."

The Shanghai Communique issued on Feb 28, one day before Nixon's departure from China, did not shy away from publicizing those conflicting views. "It was Zhou's idea that we put in our disagreements before we put in the areas where we would try to cooperate," Freeman said. "I think it was brilliant. It accomplished the purpose and allowed both sides to show to their respective friends and allies that they had held the line.

"The Chinese translators had bent over backwards to faithfully render the reservations of the United States in the communique," said Freeman, who was asked to review the Chinese text of the communique in Shanghai before its publication, together with Ji Chaozhu, a Chinese translator for the Nixon trip, who later became the Under-secretary General of the United Nations between 1991 and 1996. Ji passed away in April last year.

The most contentious issue was Taiwan. On October 25, 1971, the People's Republic of China was admitted into the UN, as "the world rebelled against the absurdity" of the notion that Taipei, not Beijing, was both the legal capital of China and entitled to represent China internationally"-to quote from a Freeman speech to the Salon of the Committee for the Republic last year.

"Both (Taipei and Beijing) were adamant that there was, should, and could be only one China, of which Taiwan was a part. ... When he visited Beijing in 1972 president Nixon solemnly declared in writing that the United States did 'not challenge' the cross-Straits consensus on this," Freeman said in the speech.

"Beijing accepted Nixon's declaration as the renunciation of any ongoing American intent to divide China by creating 'one China, one Taiwan', 'one China, two governments', 'two Chinas', an 'independent Taiwan' or by advocating that 'the status of Taiwan remains to be determined'."

Euphoria was Freeman's word of choice when asked about the mood on the plane back to the US. Coincidentally on July 11, 1971, when Kissinger arrived back in Pakistan after his secret meeting with Zhou, he cabled a single-word response to Washington-"Eureka."

After the Nixon trip, Freeman, who was "besieged by people with tape recorders who had come in to receive wisdom from the front", saw "a great outburst of misguided interest in China trade on the part of people throughout the country". One involved a man in Texas who read Pearl Buck, thought Chinese slept in their coffins before they died and was trying to sell a lot of them.

"We wanted to have an organization that would educate people-one that was officially created but of a non-governmental nature," said Freeman, who was then the economic/commercial officer for China with the US Department of State. The result was the formation in 1973 of the National Council for US-China Trade, later renamed the US-China Business Council.

In the meantime Freeman had also become a hot commodity on university campuses, to which the Nixon administration had been unable to send any speakers before the China trip because of widespread anti-Vietnam War protests.

However, what was most interesting for Freeman to observe was a "sudden, strange fascination" by US right-wingers with China, where "they discovered a society in which students sat straight upright in their chairs, had short hair, respected their elders and adhered to family values of a sort that were then already nothing but a matter of nostalgia in the United States".

In the spring of 1973 Freeman was briefly in Beijing for the opening of the US Liaison Office. And when Xu Shangwei and his wife Wang Hongbao, two young diplomats from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, were in Washington to help set up the Chinese Liaison Office there, they were warmly welcomed by Freeman.

"We were roughly of the same age and level with Chas, and that really helped draw us closer," said Wang, in his 80s, whom Freeman first met in 1972 and whom he called "one of the few Chinese friends of mine who's still alive".

"While we were in Washington, Chas invited us to dinner at his home-he's a big fan of Chinese food," Wang said. "He also recommended books for us to read, connected us with various nongovernmental organizations, and even showed us his paycheck once when we talked about our salaries."

On March 1, 1979, the US Liaison Office was converted to an embassy as the two countries established formal diplomatic ties at the beginning of that year, a long-overdue moment Freeman contributed to as part of the Department of State's China Normalization Working Group.

In early autumn the same year Freeman encountered a man selling noodle soup at the corner of Chang'an Avenue, just off Tiananmen Square in Beijing. "I bought a bowl and asked the vendor what work unit he belonged to. He replied, 'I am my own work unit.'"

About nine months earlier, in December 1978, the 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party was held in Beijing, a meeting that, by officially putting China on the path of reform and opening up, "had launched a second revolution", Freeman said.

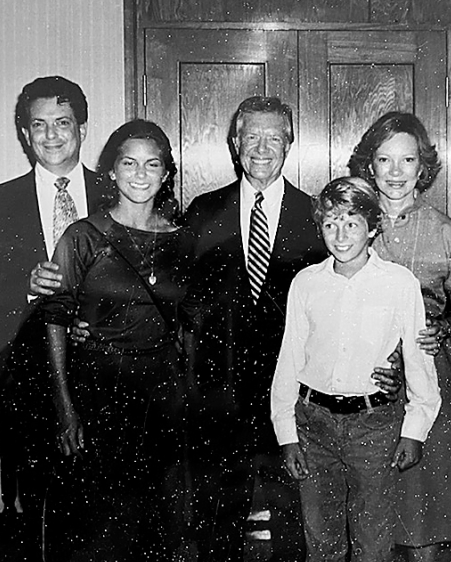

"I knew China would change, but I never imagined how much and how fast it has changed," said Freeman, who acted as deputy chief of mission in the US embassy in Beijing between 1981 and 1984 and who made sure that his own children were there to see it as China "burst into color".

Carla Freeman, his daughter, who "jumped at the chance to study at the Beijing Language Institute", to use her words, today remembers "exploring the city on my Flying Pigeon bicycle".

Her younger brother, who was given her father's name Charles, spent several of his high-school vacations in the ancient capital. Relishing a historic moment when "the two countries came together on a people-to-people basis", he still harbors fond memories for "the old-timers of Beijing who sat around, drank tea and played with their cricket". He later did his postgraduate studies on Asia and economics at Fudan University in Shanghai.

To this day both remain engaged with China. Carla Freeman, who now directs the Foreign Policy Institute of the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, traveled extensively in northeastern China, the heartland of its heavy industry, between 1994 and 1997 doing research on the regional impact of China's economic reform.

The brother, now senior vice president for Asia at the US Chamber of Commerce, served as principal US trade negotiator with China between 2002 and 2005, just after China joined the World Trade Organization.

And both witnessed the very beginning of their father's involvement with China, as he learned Chinese in Taiwan with "a rambunctious young family in tow", to quote Carla Freeman. (The father has another, younger son who was only 1 when the family moved to Taiwan, and who learned Chinese before he did English.)

"Our home was an entirely Chinese-speaking household during this time, with my father translating our story books into Chinese for us,"Carla Freeman said.

"If you wanted anything you had to say it in Chinese," said Charles the son.

"My dad was extremely disciplined. I remember he had these note cards with Chinese characters and usages all over the house."

If you listen to the diplomat himself, it was the family gene at play."Two of my own great grandfathers worked in China. One of them, Chas Wellman, after whom I was named, was hired by the Qing court to help upgrade the Chinese steel industry in around 1900," said Freeman senior. "The other, John Ripley Freeman, taught briefly at Yenching University in Beijing around 1915."

Freeman became interested in geopolitics as a law student in the mid-1960s. One of the books he read was Kissinger's A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-1822, on the balancing of power in Europe.

"The United States and the Soviet Union were at daggers drawn," he said. "I thought we would have to reach out to China. I wanted to be there when it happened."

Foresight and hard work paid off, allowing Freeman a front-row seat in Sino-US relations, sometimes quite literally. In April 1984, when president Ronald Reagan visited China, Freeman found himself "riding around in the car with the president, probably for about six hours."

He was also a close participant in the difficult and prolonged negotiations that led to the issuing of the 1982 US-China Communique on Arms Sales to Taiwan. Some of the later negotiations were carried out over a dinner table at his residence in Beijing, Freeman said.

Reflecting on the conflicts the two countries had then and now, Freeman said, "They are very different because then the major thrust was toward improved relations and the minor element was the opposition to that. Now, those who want to improve relations are the absolute minority", referring to the hawkishness of the US administration toward China.

Asked what lay behind the success of Nixon's trip to China Freeman answered "good preparation", "efforts from both sides to turn public opinion around" and "a strategic idea at the right time".

"When either Nixon or Mao saw a strategic opportunity for his country, each proved able to set aside both prejudice and the conventional wisdom to seize it," Freeman said during a speech in 2019 at the Woodrow Wilson Center titled "Nixon's China Legacy and its Contemporary Reversal".

"In 1972 the United States and China set aside ideological differences to pursue some common interests," he said. "The United States now sees such differences as impediments to cooperation with China even on obvious common interests."

On July 23 last year, Mike Pompeo, secretary of state in the administration of Donald Trump, delivered an incendiary speech at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California. Declaring American engagement with China since Nixon "a failure", Pompeo "completed the trashing of the 'one-China' stipulation by declaring-inaccurately-that 'Taiwan has not been part of China'", Freeman said.

Freeman clearly saw it coming."Over the nearly 50 years since the Nixon administration first embraced the notion of 'one-China', it served as the essential underpinning of Sino-American peace and the absence of armed conflict in the Taiwan Straits," Freeman said in December. "But it was constantly chipped away at by opponents of Sino-American normalization ...anti-Communists, and-more recently-advocates of great power rivalry and confrontation with China."

On April 8 the 280-page draft Strategic Competition Act of 2021 was introduced by the US Senate foreign relations committee. The bill, a bipartisan agreement on new comprehensive China legislation, seeks to mandate diplomatic and security initiatives to counteract Beijing. It describes sanctions as "a powerful tool" for the US and stresses the need to "prioritize the military investments necessary to achieve United States political objectives in the Indo-Pacific".

The chill is felt by all who have built a career on the now-deteriorating Sino-US relationship, including Carla Freeman and her brother.

"The commercial and business relationship has been the thing that's held the US and China together for decades," Charles the son said."But it's seen today as a greater source of tension than alignment."

A little more than 51 years ago, on April 1, 1970, Nixon, in anticipation of a relaxed bilateral relationship, announced the easing of trade controls with China. Between 1979 and 1981, when Freeman acted as the director of Chinese affairs in the State Department, he witnessed Sino-US collaboration in areas from astronomy and geology to education and agriculture."Both Chinese soybeans and sows were of great agricultural and scientific interest to us," he said.

Joining her father in 2016 at an event titled "Two Freemans and a Changing China", held at the Center for China-US Cooperation at the University of Denver, Carla Freeman provided her own observation. "My father spoke about empathy as a key tool in diplomacy and how that can be a source of confusion to non-diplomats...As an academic focused on aspects of contemporary Chinese policy, the presentation of Chinese perspectives unadulterated by normative interpretation also runs the risk of rebuke - in Washington especially, those seem as too empathetic to China can be dismissed or even decried as 'panda huggers' among other appellations." she said.

Yet the diplomat, who was assistant secretary of defense between 1993 and 1994 after having been US ambassador to Saudi Arabia between 1989 and 1992, considered empathy essential in 1972.

"I find it noteworthy that the most belligerently anti-Chinese members of the current US Senate are also its youngest" who "have no experience of its (the Cold War's) anxieties" and "appear to take its sudden end as predestined", said the diplomat, who believes that to compare the current Sino-US confrontation to the Cold War of 1947-1991 is "profoundly misleading and delusional".

"The US-China contention is far broader than that of the Cold War, in part because China ... is part of the same global society as the United States. China is now fully integrated into the global economic system and cannot be walled off from it."

Looking back to what Nixon called "the week that changed the world", Freeman said that being part of it has given him a long-term commitment to China and enabled him to take part in the shaping of Sino-US relations in their most "malleable and creative" years.

"To recall this (the Nixon trip) is to remember the narrowness and precariousness of the strategic reasons that brought the US and the People's Republic of China together. We were starting from complete estrangement and reaching for a common understanding," Freeman said.

zhaoxu@chinadailyusa.com