Emotional response

As well as overcoming the physical challenges posed by COVID-19, there is a need to tackle the psychological fallout from the pandemic, Li Yingxue reports.

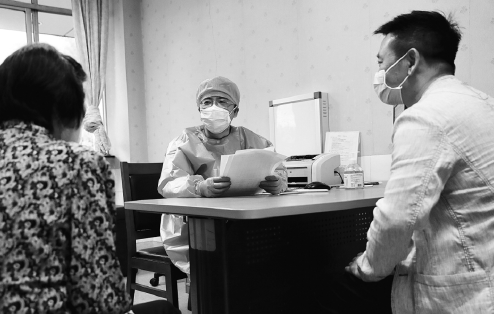

Five days after Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, was locked down in January, Liu Zhengkui and his team started an operation of psychological assistance and psychological crisis intervention to help people at the epicenter of the pandemic.

"Usually we start the operation right away when an emergency happens, but the pandemic is different because it's an infectious disease, so it took us a couple days to figure out how to proceed," Liu, a researcher at Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, explains.

Liu spent almost three months in Wuhan providing psychological assistance to local medical workers, recovered COVID-19 patients and community staff since March. At the end of August, he will return to continue his work.

Initially, the operation was planned to last for a year, but recently Liu's team has managed to secure the funding and support to extend it by two years.

"Large-scale disasters always have long-term influence on people. For people in the core area of the Wenchuan earthquake, its influence has lasted for five years," Liu says. "The influence of the pandemic may last as long as three years for people in Wuhan."

Liu says when a disaster happens, the public's attitude usually goes through three steps-nervous and terrified first, then angry, before gradually going back to normal.

"In the first phase, people think their lives are threatened, and then, when they realize their lives or work are unaffected by the disaster, society needs an emotional release and the anger will gradually fade away over time," Liu explains.

In Liu's mind, as transmission prevention has become the norm, the public's mentality also flows into a new phase.

"Social distancing is still required, which will affect people's emotions. There are occasionally new cases showing up in some places in China, which will still make people in those locales feel nervous again," Liu says.

"The prompt reaction to control the spread of the pandemic when it reoccurs will calm local people more quickly than the first wave, such as the cluster of cases which originated at Beijing's Xinfadi wholesale market," he says.

A seven-day self-help online training camp was launched by Liu's team at the end of January. A special version of the training camp for medical workers went online on Feb 23 followed by a version for parents and children.

The training camp takes one person 10 to 20 minutes each day to learn how to cope with stress and manage their emotions.

According to Liu, the core content of the training camp is based on the courses and intervention plans that are recommended by the WHO and the Chinese Psychological Society, and have been widely applied in many post-disaster psychological rebuilding operations worldwide.

"The content is combined with psychology research literature and also experiential decompression training," Liu adds.

"We also have an online psychological counseling team. If there are situations that the person who takes part in the camp cannot deal with alone, the specialists will offer help," he says.

So far, around 250,000 people have finished this online training camp, Liu says.

Liu's team was founded in 2008.They helped people affected by the Wenchuan earthquake. The team includes six tutors and a dozen students.

Liu says the strength of one team is not enough. Therefore, their team produced a list of more than 800 psychology service institutions across the country and trained them to be able to help their local communities.

Technology has also played an important role in this operation. More than 1,000 smart bracelets have been distributed to medical workers, recovered COVID-19 patients and community staff.

"The bracelet can warn people if he or she has a violent mood swing and push some information about how to manage the emotions," Liu says.

Besides helping in Wuhan, Liu's team has also opened a nationwide hotline for people to ask for help. More than 400 experienced psychological counselors take shifts to answer the calls.

Li Huijie, a member of the National Alliance of Psychological Aid, is one of the volunteers manning the phones for the hotline.

Li stresses that it's normal for the public to experience feelings of worry, fear and anxiety, and people should understand and accept this situation.

"When a crisis happens, some people will exhibit certain emotional and physical behaviors they would otherwise not display. It is a normal reaction for people in an abnormal situation," Li explains.

Li says the pandemic has affected the five basic needs of people-a sense of safety, trust and control, self-esteem and affinity. As the pandemic is brought under control and the economy begins to recover, the psychological impact of the pandemic is fading.

"Each person should have a little knowledge about psychological crisis intervention and learn some scientific methods to self-regulate when a crisis happens," she says, adding that once people feel they can't live their normal life, with regular social contacts or a feeling of happiness, they can ask for professional help.

According to Liu, so far there are more than 6,500 cases of people who have contacted the hotline asking for help.

Jiang Changqing, chief physician at department of clinical psychology, Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, says that the tension in intimate relationships and parent-child relationships is a prominent problem alongside anxiety and fear for the public during the pandemic.

"For people, the social functions include work, interpersonal communication and also family life, and if people only put focus on one aspect, it's easy to cause problems," Jiang explains.

Jiang says a key rule to regulate the relationships between parents and their children or couples is to maintain self-censorship and ask whether the goal and the action are consistent.

"Usually, in most families, the intention is good, so people need to reflect whether their behavior is good or bad, and make sure to act in a way that is conducive to accomplishing what they want," Jiang says.

"For example, if you want your child to make progress, by making too many negative comments, you may not achieve the desired goal," he says.

During the pandemic, for people who live alone, Jiang says they need to keep in touch with their family and friends, as close family contact and social support is an important foundation to a sense of security.

Jiang says that, even though the pandemic has limited people's sphere of activities, the public should try to maintain their regular schedule and get their life back to normal.

"Rules and a sense of control is a dose of good medicine for anxiety and panic," Jiang says.

He advocates for people to "self-check" by communicating with friends and family to find out whether or not they are exhibiting any change in their behavior, or acting more-or less-cautious than they should be.

"For example, if someone is wearing a protective suit, an N95 mask and goggles to go out while others are just wearing masks, it shows signs of over cautious behavior," Jiang says.

As well as learning the procedures for, and scientific reasons behind, the various pandemic prevention measures, practice is another way to strengthen the sense of control.

"This can be seen with medical workers in Wuhan. They may have felt a bit afraid when they entered the negative pressure ward to treat the COVID-19 patients, but after practicing for several days, they became sure that if they followed the necessary safety measures step-by-step, they wouldn't be infected," Jiang says.

Jiang arrived in Wuhan on Feb 20, to help the medical assistance team from Beijing. According to him, around 28 percent of the medical workers often have insomnia or their sleep is restless and filled with vivid dreams, and less than half of them have problems with their appetite or digestion due to the pressure and nervousness they experienced.

Liu and his team arrived in Wuhan on March 3. Their main focus was the medical workers and the COVID-19 patients.

Liu later noticed that the city's front line community workers were also under a lot of pressure during the pandemic, so his team decided to expand their scope of help.

According to Liu, Zhang Dingyu, head of Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, arranged for all front line medical workers to take turns in taking two weeks' leave.

"The break can help them to deal with their emotions," Liu explains. "Zhang also asked our team to arrange training for them to enhance their psychological resilience, as well as to learn how to help the patients manage their emotions if there is a second wave of the pandemic," Liu says.

Today's Top News

- China's data industry more than doubles in market size during 2021-2025 period

- Loan subsidies set to boost consumption

- Young people redefining summer tourism

- Protectionist's paradox could revitalize WTO

- Anti-aggression spirit still inspiring today

- Momentum builds in A-share market