Hotpot magic casts a new spell

A documentary highlights the legendary dish's different styles to present a taste of tradition, Li Yingxue reports.

A copper hotpot on a charcoal fire, thinly sliced meat and a bowl of sesame sauce, chili oil and fermented bean curd. These are the ingredients that make a traditional Beijing instant-boiled mutton hotpot.

The steaming, succulent hotpot is a celebration of life, friendship and taste. Anyone watching the magic of the ingredients coming together will have to battle a severe case of mouthwatering anticipation. The trouble is it is being watched on a computer screen.

The COVID-19 outbreak has prevented people from eating out for a month. According to data on Sina Weibo, the food or meal most people missed is hotpot.

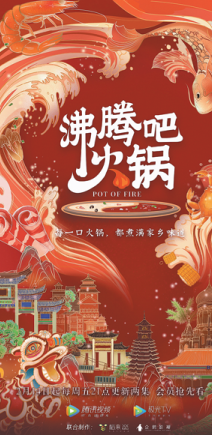

A new documentary, Pot of Fire, went online on Tencent Video on Feb 14, allowing netizens to "enjoy" hotpot together on the internet.

With two new episodes released each Friday, the documentary allows the audience to relish different flavors of hotpot from south to north across China-the first six episodes have been viewed more than 40 million times.

From Beijing-style lamb hotpot to Chaoshan-style beef hotpot, the 10-episode documentary introduces 10 different flavors of hotpot-even some niche flavors such as a sour-and-spicy flavor from Hainan province.

Each flavor also represents a city and the characteristics of its residents.

According to general director Qu Nan, the crew took one year to prepare, shoot and produce the documentary.

"We hope to use modern expressions to present a warm hotpot documentary for the audience," she says.

Qu's team selected 10 styles of hotpot from around 50 possibilities.

Hotpot in different seasons is also showcased. The crew waited until the end of last year to shoot hotpot being made in Northeast China with pickled cabbage.

The second episode is about the legendary and some might say the spiritual home of the dish, Chongqing hotpot. With thousands of hotpot restaurants in the city, this was no easy task, Qu says.

"We don't want to just show the hotpot. The food is linked to the people and their stories."

Qu uses three rules as criteria to select restaurants to feature. It must be a small restaurant, must have been opened for more than a decade and the owner must still make hotpot.

"The couple we filmed in Chongqing have been making hotpot for three decades. Each day they have to work until 2 o'clock in the morning. What surprised us is that they are not complaining about the hard work. A cup of baijiu (white liquor) or a meal of hotpot makes them happy," Qu says.

Qu has been producing documentaries for more than a decade. Pot of Fire is her first in the food sector.

"It's hard to film food, especially hotpot, because you need to capture the smoke and the boiling water," says the 41-year-old director. "It's not about using the most advanced equipment, but to find the best combination to film."

Qu's team designed an innovative way to solve the problem that the condensation and smoke of the hotpot would make the lens fuzzy. They figured out a simple but ingenious solution-attach a small fan on the camera.

"The color of a pot of chicken soup is changing all the time as the chicken is boiled. Sometimes you need to make another pot for the shoot," she says.

There are two common comments on the documentary-one is "it makes me hungry" and the other one is "I have to eat something while watching it".

Qu has a team to collect and analyze the feedback from the audience, and she also checks on the danmu, or short live comments.

"Thanks to the internet, it's amazing how fast you can get the reaction from the audience, and their reviews are so precise and professional," she says.

Each episode lasts around 12 minutes-the shorter time is to suit the fragmented time for the young viewers.

"However, the audience might think the length is not long enough, maybe because the novel coronavirus outbreak means people might have more time on their hands," Qu says.

The cartoon images of the ingredients shown in the documentary add a sense of fashion which Qu purposely chose to attract a young audience.

The voice-over is done by Jiang Guangtao, a popular dubber who is also the voice of Jack in Titanic's Chinese version.

"Jiang's voice is versatile. For this food documentary, he finds a warm and genuine voice to tell the story which quite fits our show,"Qu says.

The documentary is a salute to the medical staff fighting the virus on the front line and also a comfort for people who have to stay at home due to the outbreak.

"No food other than hotpot can represent how much Chinese like to gather together to enjoy happiness. I believe spring will finally come after the outbreak," Qu says.

"We need the courage to face life, and even some humor when dealing with difficulties. I hope this documentary can bring the audience some strength, which I believe we already have."

Today's Top News

- Crossing a milestone in the journey called Sinology

- China-Russia media forum held in Beijing

- Where mobility will drive China and the West

- HK community strongly supports Lai's conviction

- Japan paying high price for PM's rhetoric

- Japan's move to mislead public firmly opposed