Sights, sounds and scents from a sparkling thread

An exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum is encouraging school students to think about the meaning of the ancient Silk Road

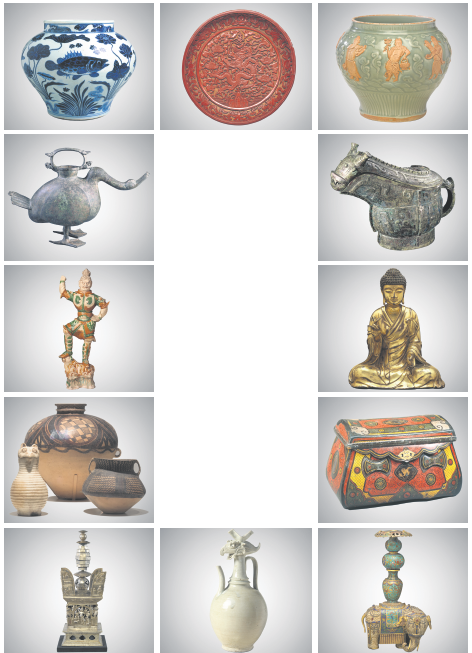

There's nothing wildly unusual about a piece of blue-and-white porcelain from ancient China. After all, every museum with a China collection seems to have one or two, if not a couple dozen, of them. But for Susan Beningson, curator of Chinese art at the Brooklyn Museum, a 14th-century wine jar with blue-painted fish and aquatic plants provides an entry point to the museum's newly installed China gallery. "This is one of the great masterworks of our museum's much-prided ceramic collection," she said in late October, when the gallery opened after a six-year renovation.

It was produced by the imperially sponsored kilns of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province at a time when blue and white ceramics were luxury goods, she said.

"If you look really closely, you can detect flecks of black in the rich cobalt blue paint. This points unequivocally to the mineral mined in Western Asia, from where it was exported across the ancient Silk Road to China for use by its craftsmen."

She was referring to the trans-Eurasian trade network that linked China with vast land to its west, from little kingdoms scattered across the Gobi Desert to the shore of the Mediterranean and Rome.

On top of its position in the history of international trade, the jar offers a case study in how ancient Chinese relied on homophones to do well-wishing.

While fish (yu), shares the same pronunciation with a word meaning surplus, the lotus flower (lian), provides a rebus for the idea of continuity. Put together, they fulfill a major Chinese longing, to be seriously spoiled by ceaseless abundance.

The jar was part of a large bequest of Chinese ceramics from the Hutchins family collection in Long Island, New York, Beningson said.

"When the father died in 1952, the son invited the then curator of Chinese art to go to the estate on Long Island and pick things. But this was not initially among the things chosen from the rather dusty collection. Before the curator left, he went to wash his hands on a sink in the garage, and the fish jar was under the sink catching drips of water. The curator asked: 'Can we have that too?' And they said yes. The jar was then put on the truck and came to Brooklyn."

In fact, if you listen to Beningson, the new China gallery showing, which features 140 pieces, is as much about the formation of the museum's remarkable Chinese collection as it is about Chinese art, ancient and modern.

Cloisonne wares, the other strength of the museum apart from porcelain, came in 1909, donated by an American collector in Brooklyn whose brother lived in Beijing and was in charge of buying antiques and sending them to the New York borough.

In another example, a first-century bronze mirror on view was bought by Stewart Culin (1858-1929), the museum's first curator of non-Western art, who traveled to Asia, including China, between 1909 and 1912.

"We know from his diligently kept journal that he bought this in an antique store in Shanghai for two dollars and 40 cents," Benington said. "We have his receipt. More an ethnographer than an art historian, Culin was interested in people's daily lives. So if he went to a restaurant in Shanghai he kept the menu and put it in his archives, which are now all with us."

Beningson intends to tell stories with the exhibits, about one third to half of which are either new to the collection or have not been on view for decades.

"Our display is only vaguely chronological. I want there to be narratives in different places so that if somebody comes in and doesn't want to spend hours going through the cases, he can just go to one case and can still get a good story and a good time."

Items that offer tantalizing glimpses into the lives of ancient Chinese include bronze belt hooks inlaid with gold threads; gemstone-embedded animal mat weights used to keep the floor mattress in place while people shuffled and moved on it; and a tiger-shaped ceramic pillow that inevitably raises the question of comfort in the mind of curious visitors.

Both the hooks and the weights are from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), a period of territorial expansion and cultural prosperity closely associated with the forming of Chinese civilization and the opening of the Silk Road.

About 139 BC an envoy of the Han emperor Wudi embarked on a westward journey led by a man named Zhang Qian. The journey eventually took them 10 years, most of it spent in the captivity of the nomadic Xiongnu people (arguably the ancestors of the Huns who later posed a serious threat to the declining Roman Empire). For the next millennium until the 10th century the footsteps of these intrepid men were followed in both ways by equally adventurous merchants and their caravans, who trekked and traded on the 8,000-kilometer terrestrial route, before more maritime options became available.

Beningson was quick to point out that Chang'an (modern-day Xi'an), the capital of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24), was nearly three times the size of Rome, four times larger than Alexandria, Egypt, and 17 times bigger than Byzantium.

However, it was the winding trading route that has acted as a sparkling thread for Beningson the storyweaver.

A lot of that story can be found in the depth of the blue, the 14th-century ceramic fish jar being one example. One of its predecessors, an exuberantly painted third-century BC pottery vase, testifies to the beginning of those exchanges. The blue pigment on it was derived from lapis lazuli, for which Afghanistan was known two millennia ago as well as today.

The Silk Road entered its heyday during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Transmitted along the road were not only gleaming gemstones and glistening metal wares, but also animals (rhinoceroses and elephants) and people (the Sogdians who dominated the Silk Road trade for several centuries), sounds (Sogdian music), sights (Sogdian dance) and scents (the various spices for tasting and for burning in front of the Buddha, whose influence spread along the road).

More often, a single object holds multiple clues, shedding light on the truly international nature of the trade going on at the time.

A 10th-century ceramic ewer sports a phoenix head that points to the influence of Sasanian gold and silver wares, a much sought-after luxury on the Silk Road. Meanwhile, its full body of fine white clay asserts its noble association with the royal kiln of Jingdezhen, as opposed to other, less-celebrated ones in China's coastal south.

It came into the museum collection in 1954, and the person who donated it said that it originally came from Indonesia, Beningson said.

"Maritime trade between China and Southeast Asia was greatly expanded in the late 10th century, when the Tang Dynasty was replaced by its successor, Song."

Here two story lines, the terrestrial Silk Road and what is dubbed today in China as the Maritime Silk Road, intersected.

Having done training sessions with primary schoolteachers from Brooklyn last summer, Beningson is well aware of the impact a museum visit may have on children.

"When they come into the museum, that might be their first exposure to China.… I really want to use art to tell stories about Chinese history and civilization. I want to hook them young. If they get very excited about China now, it may stay with them for their whole life, like what has happened with me."

The Brooklyn public schools in the third grade have a unit on Tang Dynasty Silk Road and global, Beningson said.

"Our exhibition in that part is organized for them."

Pearl Lau, who has taught art in Brooklyn for 18 years, and who recently retired as an elementary schoolteacher, has taken part in the museum's Summer Teacher Institute partly presided over by Beningson.

"It's important to know as a forming human that the whole world is responsible for what we take for granted," Lau said.

"Invent writing? China, Egypt, Maya and Sumeria. Invent the zero? Arabic and Mayan people. Ideas are exchanged, and the Silk Road offers the perfect example of trade and culture and gets students to think, for example, what kinds of instruments were introduced along the path and why. In the meantime, such study empowers minority students including the Chinese and Muslims, as it created a 'Wow!' from the kids who have been learning about their American-European culture all along."

Animals have a big role to play, Lau said.

"What better way to hook kids than to talk about animals? I introduced how to travel across the desert with your camel, packing enough water for the horses from the Pamir mountains, meeting dancing girls in Kashgar, what instruments you would be playing, etc."

Beningson herself has envisioned school students doing animal-themed tours inside the gallery, with items ranging from ram mat weight and elephant cloisonne to a goose-shaped bronze wine jar, whose crooked neck and tentatively uplifted head vividly conveys the bird's agility and timidity.

They can also study the star maps used by ancient Chinese for celestial navigation in their next life, she said. A Han Dynasty bronze, labeled "Star and Cloud Mirror", contains on its patinated sphere constellations of rising and setting stars, with the central knob presenting the polar star, the star of all stars for ancient Chinese astronomers.

"Or, they can trade superpowers like what they do with their Pokemon cards," Beningson said, pointing to the "Immortal Jar", a fine celadon porcelain around whose big belly the images of eight immortal friends from Chinese folklore are depicted.

"We put on explanatory notes detailing the magic each of them has, and we plan to issue trading cards… The whole thing is really geared toward our young visitors."

The museum's education department, with a grant from the Freeman Foundation, is putting together a brochure on Chinese, Japanese and Korean art for teachers based on the museum's collection. The brochure will be in three languages: English, Chinese and Spanish, reflecting the diverse ethnic communities in Brooklyn.

"There will be a lot of background information-the list of dynasties and maps of the Silk Road, for example-in brochures to help teachers when they teach that unit," Beningson said.

"We'll talk about the difference between porcelain and earthenware, as well as the difference between Buddhism, Taoism and Shintoism," she said, referring to the interconnected religions and thoughts that shaped societies in East Asia.

The Japan Gallery had a joint opening with the China Gallery two years after the reopening of the Korean Gallery in 2017. The three adjacent galleries, reachable through a staircase from the great hall, make Brooklyn Museum "one of the few museums in the US that has given prominent location to non-Western arts", said David Berliner, the museum's president and chief operating officer.

Two other things that Beningson is keen to get across through the China Gallery is the creativity and diversity of Chinese culture.

"People talk about China as if it's a monolith, but it's not a monolith," she said.

She sets out to debunk the myth by pairing ancient ritual bronzes unearthed from the central plains with those excavated from the empire's peripheries on the far north and south, and by juxtaposing the sober, demure-looking Song Dynasty porcelain with a shimmering silver saddle, engraved and repoussed with phoenix motif, from the Empire of Liao (916-1125), whose horse-mounted troops harassed and pillaged the Song borders in the 10th century. The inspiration for the saddle came as much from Silk Road silver as from the Song people's love of high-relief ornaments on metalwares.

Throughout Chinese history, artists and artisans have constantly looked beyond borders and into the past. Very often the same prototype was adopted to serve different purposes. While a bronze brazier from the Han Dynasty was used to warm wine, a celadon-colored ceramic tripod clearly modeled on the ancient bronze is most likely to have appeared on an altar, as an incense burner.

Antiquarianism is a tradition, a sentiment, an undercurrent to aesthetical development, and an often-overlooked force for Chinese culture's constant self-reinvention.

In 2013, with the financial support from the City of New York, the Brooklyn Museum tore out the old galleries for arts of Asian and the Islamic World. What followed was not only the laying of ducts and vents and the introduction of climate control, but also the extensive research and conservation work of the museum's China and Japan collection, a large part of which is now more ready than ever to greet the public.

The China Gallery ended at one side on a 12th-to-13th-century lacquered leather trunk used by what the wall texts identify as "a discerning elite world traveler on the ancient Silk Road".

The decorative techniques used here are called "engraved gold" and "engraved color", in which gold leaf, powder or pigmented lacquer is placed in lines embedded in the lacquer ground. The same method was widely adopted in making Islamic book covers.

While the multiple design motifs relate to silk textiles from Central Asia, the central medallion depicts a dancing lion ubiquitous in the visual culture of ancient China.

Under the front of the lid is a line of Chinese inscription that means "Made by the Ou family of Wenzhou, Xinhe Street, Anning Ward". Wenzhou, in Zhejiang province, has been a center of lacquer production since the 10th century. From the mid-14th century superbly made Chinese lacquers like this were exported in large quantity to Egypt, eastern Iran and Central Asia.

Brooklyn Museum's China story is deeply embedded in the narrative tableau of global exchanges, cultural and commercial.

And in very much the same way the gold lines were set off by the red and black background, this China story is being accentuated and completed by many other stories that are just as relevant, but that have rarely been fully understood.

Today's Top News

- Experts: Decoupling disastrous for Japan

- Nation boosts foreign-related rule of law

- HKSAR holds legislative election

- Nation's electric truck sector sees robust growth

- Vote for good governance in Hong Kong: Editorial

- China blasts Japan over radar-illumination claim, warns against 'militarism'