Return from heaven

Tashi Tsering, still lean and tough at age 37, is a special breed - one of only a handful of humans physically capable of full function at the top of the world. He is adapted to extremes.

Friends call him Tatse. Born and raised at the foot of the snow-capped Himalayas, he is one of the few who can reach the world's highest summits without supplemental oxygen.

In 2014, the government of the Tibet autonomous region asked Tatse and other top guides to move corpses entombed in the ice, mostly between 7,300 and 8,500 meters, to give them new resting places out of sight in caves, behind large rocks or beneath the snow. It was the first step in a plan to bring them down.

Tatse gained strength for the macabre duty by chanting a six-syllable prayer - om mani padme hum - signifying the transformation of earthly things to the pure exalted body and mind of a Buddha. He used his ice axe to chop out the remains of nine bodies, and he and other guides gently carried them away from the main climbing route.

He worked quickly because of the frightful nature of the task and to avoid frostbite.

But for Tatse the mountain is not all terror, drudgery or even business. It's a place of serenity. For him, it is heaven.

A SPIRITUAL CALLING

When people from the flat land of civilization look up at Qomolangma, they may imagine only the geological forces they learned about in school science classes. Not so with the Tibetan guides. They find something profound and infinite in the wind, ice and rocks framed by an electric-blue sky. They see the domain of gods.

On April 19, the day climbing began this year, Tatse and his fellow guides, all of them bronzed and sinewy, performed an ancient ritual at the foot of Qomolangma.

Circling piles of rocks hung with Tibetan prayer flags, the guides chanted "Suo ... suo... suo" - victory - throwing paper strips of scriptures into the chilly air. They burned juniper branches, producing fragrant smoke, like incense, as an offering to the female mountain god.

Then they lined up facing the peaks, pressed their palms together in devotion and prayed for her to bless them on the coming ascent. It's the same before every climb: They commit their lives to the effort.

In his mind during the prayer, Tatse expressed the purity of his motives: "I have no intent to harm you at all. This is my work. Please protect me from hidden dangers. I trust my safety to you."

Tatse promised to remove trash from the mountain and to avoid making "big sounds". Noise is thought to irritate the gods, who may then retaliate by bringing bad weather - the climbers' greatest fear.

"We humans are fragile before nature," Tatse said. "I always want to climb with a worshipful mind and heart."

FINDING A BALANCE

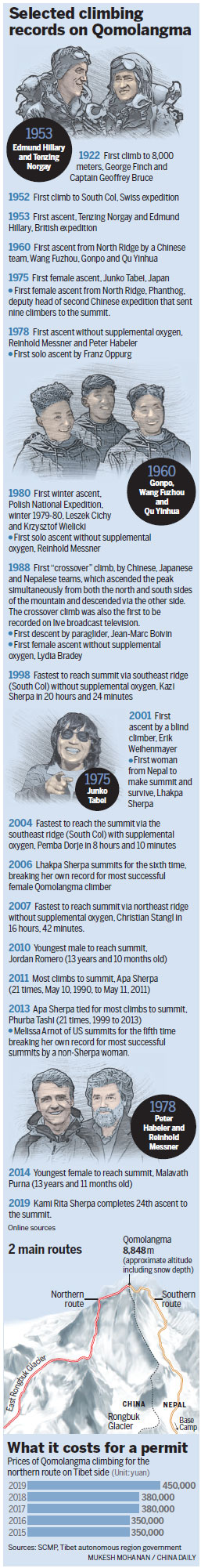

Over the past two decades, the regional government has been working to turn mountain climbing into a major industry. With five peaks rising above 8,000 meters, 70 above 7,000 meters and more than 1,000 above 6,000 meters, Tibet is a mountaineering magnet.

Nyima Tsering, an outstanding climber and head of the region's sports bureau, founded the Tibet Mountaineering Guide School in 1999, producing top guides to lead paying customers in the dangerous game - usually one guide for each, although they may move in groups on the mountain. Tatse and another climber, Tashi Phuntsok, were the school's first graduates in 2001. More than 300 have been trained since.

The school is supported financially by the for-profit Tibet Himalaya Mountaineering Expedition Co, founded in 2001. It offers jobs to trained guides and provides commercial climbing services for a number of Himalayan peaks.