Sri Lanka had 'no history of Islamic militancy'

While home-grown suicide bombers were suspected to have carried out the Easter Sunday bombings in Sri Lanka, many in that country are in disbelief.

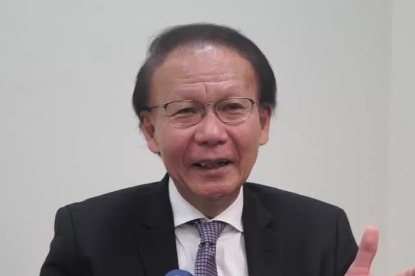

"Nobody expected this (violence) from Sri Lankan Muslims," said Alan Keenan, a senior Sri Lanka analyst at the Brusselsbased research firm International Crisis Group.

He said Muslims supported the Sri Lankan government in crushing the separatist Tamil Tigers group a decade ago. They never attacked any other group on religious grounds. Prior to the bombings, the island nation had no history of Islamic militancy, he said.

The Sri Lankan Muslims were the first to warn about Zahran Hashim, a firebrand cleric believed to have links with the Islamic State. Hashim founded the National Thowheeth Jamaath, or NTJ, a local extremist group on police radar for the attacks along with another group, Jammiyathul Millathu Ibrahim.

Keenan said NTJ was known to harass fellow Muslims who didn't share its extremist views. The first time that NTJ targeted other communities was in December, when the group was linked to vandalizing of Buddhist temples in Mawanella, central Sri Lanka.

The Muslim community accounts for roughly 10 percent in the Buddhist-majority nation, with most of the Muslims residing in eastern provinces. It was around this region that radical ideas started to take root, according to Chulanee Attanayake, a visiting research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, or NUS.

She said these ideas could have been spread by Sri Lankan Muslims who worked and studied in the Middle East.

ICG's Keenan said the Easter Sunday attacks "appear principally to be the fruit of seeds planted by transnational jihadists". Reuters reported Australia and Britain have each confirmed a bomber lived there before heading home years ago.

Keenan said that global Islamophobia had also gained footing in Sri Lanka, as evidenced by the March 2018 anti-Muslim riots perpetrated by a group of militant Sinhalese Buddhists. Such an anti-Muslim sentiment is fueling fear and insecurity among Sri Lankan Muslims, he said.

"The pressure they (the Muslims) are feeling encourages them to turn inward. It alienates them. They don't feel safe, they don't feel they belong, and that they're not treated equally," he said.

"Terrorism perpetrated by hardline groups is a preserve of a few who have tarnished the name of Islam and do not represent the vast majority of Muslims both in Sri Lanka and elsewhere," said Mustafa Izzuddin, a research fellow at the NUS' Institute of South Asian Studies.

Thyagi Ruwanpathirana, South Asia researcher for human rights watchdog Amnesty International, said, "Both political and religious leaders must make citizens understand it is not the Muslim community that was responsible for the attack."

Both political and religious leaders should call for unity and interfaith harmony, she said, adding that such harmony should be linked to "reflection and action against those who attack religious places of worship".

"This is a shared responsibility," said ICG's Keenan. "This is not just a 'Muslim' problem."