The first emperor of China invented Keynesian economics

China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective

The first emperor of China invented Keynesian economics

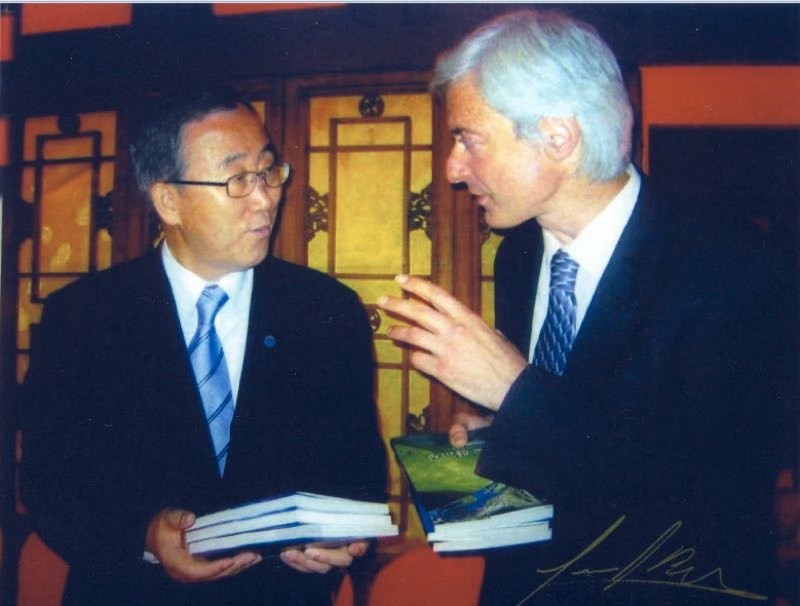

Editor's note: Laurence Brahm, first came to China as a fresh university exchange student from the US in 1981 and he has spent much of the past three and a half decades living and working in the country. He has been a lawyer, a writer, and now he is Founding Director of Himalayan Consensus and a Senior International Fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

He has captured his own story and the nation's journey in China Reform and Opening – Forty Years in Perspective. China Daily is running a series of articles starting from May 24 that reveal the changes that have taken place in the country in the past four decades. Keep track of the story by following us.

China and the United States in 2012 represented the biggest and second-biggest emitters of carbon into our planet. After attending the UNFCC COP 17 in South Africa and Rio+20 in Brazil, and watching my own country's representatives block every move toward a climate solution, it occurred to me that to have any positive impact on climate change, it may be possible to see more results through China rather than the US.

The question of combating climate change was no longer about the science – that was perfectly clear. It was about the political will of leaders who want to make a change for the better and who are willing to confront, rather than comply with, corporate interests to do so.

I dusted off former Premier Zhu Rongji's Sixteen Measures on Macro-Economic Control, the founding document of his macro-economic control system. With the help of Zhu Rongji's daughter, Zhu Yanlai, we together drafted a document, Sixteen Measures on Green Macro-Control Policy, to mirror Zhu Rongji's famous Sixteen Measures on Green Macro-Control Policy, which is considered the founding document of China's managed combination of planning and market. Both tools would be needed for the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. This kind of transition will involve reforms as complex in the decade ahead as those that occurred in the 1990s.

Following Rio + 20 in summer 2012, I returned to my studio beside the Great Wall and began to help the central government draft a single policy proposal that merged principles of planning with the market to create jobs that could combat climate change. With a leadership transition in China, I thought they might be open to new ideas. While drafting the document, I looked up from the window of my studio by the Wall with its looming towers, a kind of Da Vinci Code revealing China's economic history.

To most people the Great Wall was a vast feudal castle or defense bulwark against Mongolian and Manchurian invaders. But from an economics perspective it represented massive fiscal stimulus for infrastructure investment, using fixed assets to fuel economic growth and assure jobs. The Great Wall was not just a defense system, but a sophisticated national telecommunications program. Whether by horse relay messenger (the Wall was built wide enough for horses to run on it) or bonfire signal, one end of China's vast nation could communicate news to the other in almost real time, relative to the day.

China's 2,000-year-old telecommunications project was government fiscal funded. This was not so different from many of our technology communication undertakings today. It provided jobs for everyone from Confucian scholarly engineers to commanding generals, right down to the masses of Chinese workers who built it. While one son in every family across the empire was conscripted to work on the Wall – a cruel undertaking – this practice also assured that each family received a Keynesian cash injection to boost local spending power.

Arguably the first emperor of China invented Keynesian economics. The Wall's greatest construction periods usually coincided at times when Chinese exports surged together with its foreign exchange reserves. But each dynasty's overextension of construction coupled with a depletion of resources, led to economic downturn during that period of history. China's new economic stimulus would now have to involve fixed-asset investments into green energy solutions, financed through a new concept that would come to be known as the green bond.

While drafting the document, I sought out Lin Lin, who headed the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Beijing office, and worked closely with her future successor Sun Yiting, who is now vice secretary of the International Financial Forum (IFF) and director of the Center for Green Development. At the time he was already coordinating with China's different government departments in finding ways to develop a policy response to reduce the country's carbon footprint. Key to the success of such policy would be the role of China's financial institutions and regulatory authorities in creating financial mechanisms that would encourage businesses to become genuinely green.

"Green economy consists of two things," Sun said. "First is the economy itself. Logically it must grow, which means an increase in GDP with businesses that are profitable. Charity is nice, but should not be confused with economy. The economy is all about industry, trade, and finance. Second is green, which means in hard terms reducing the carbon footprint. That calls for a total reduction of carbon and waste. So putting the two together, how do we facilitate a boost in production and ecological conservation at the same time? This is what the green economy should be all about: Using the tools of a real economy to preserve natural resources, contributing to overall growth. That will involve technical changes to productivity and finance."

"The total reduction of carbon will only occur through either renewable or efficient energy," Sun said. "It is about real businesses reducing carbon and waste, not an accounting game on the corporate books."

This can only be achieved through environmental economics. That is, infrastructure stimulus for grid conversion requiring the government's investment, combined with credit and fiscal policy that drives businesses to adopt renewable and efficient energy for their own bottom line. In short, green finance.

So the challenge in drafting a policy document to promote the concept of ecological civilization was how to adapt finance to support a re-gridding of China's energy matrix, to transition it from fossil fuels to green energy, while creating new jobs – essentially green growth. Inspired by the Great Wall, I sought to draft a blueprint for a "Great Green Grid."

Please click here to read previous articles.