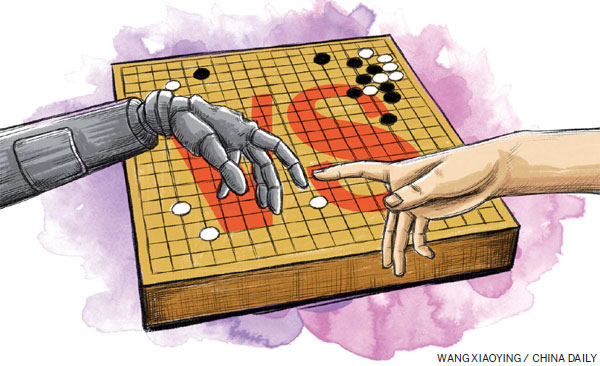

Matching wits

While AlphaGo's win over one of the world's best Go players marked a milestone in artificial intelligence advances, humans have an edge in many of the simpler tasks, such as linguistic expression

What does a board game have in common with a pet?

It turns out that Go as a game sounds like the Chinese word for dog (gou) even though the Chinese equivalent is weiqi, or literally the encircling game. That's why recently many in China have been inundated by the news that a dog has trumped humans in smartness. It was about the only scintilla of fun in an otherwise grim scenario for the human species.

Most of my compatriots were probably not paying enough attention in 1997, when IBM computer Deep Blue beat world chess champion Garry Kasparov in a match. There was not as much coverage here, plus that style of chess, known as international chess, is not widely played in China, while Go is an ancient game invented in China and most popular in Asia.

So, AlphaGo's match with Lee Sedol, which was streamed live on all major online platforms with narration and commentary, came as a big blow to anyone who considers Go to be the ultimate barrier for artificial intelligence in climbing over that of the human.

Before the match started on March 9, Chinese forecasts fell neatly into two camps: Science majors overwhelmingly took the side of the machine while Go specialists believed in the ability of one of their best to come out ahead. Needless to say, the more you pinned your hope on Lee, the more disappointed you got.

I'm not a science major and know nothing about Go. All the sci-fi movies I have seen have conditioned me to accept this as something of a given. Actually they go far beyond defeating humans at board games.

From a layman's perspective, for anything that builds on the foundation of knowledge, humans do not have a chance vis-a-vis a computer, let alone a specially equipped and programmed one. The irony is, the more specific and in-depth the knowledge is, the easier it is for a machine to commit to memory and recall for use.

Games have rules and possibilities, and a machine can outsmart a human because it can tap its storehouse instantly. Sure, Go involves strategizing, which is far more complicated than simply identifying the best out of a million possibilities. But anything that can be streamlined and quantified into a set of rules will leave humans at a disadvantage.

AlphaGo's victory was a milestone in artificial intelligence research, but it's time to move beyond it. As Deep Blue's Murray Campbell said, it marked "the end of an era ... board games are more or less done".

I have always believed that computers would be competent for highly convoluted tasks but would fail at childishly easy ones. Yes, it can memorize all the dictionaries in the world, but it wouldn't be able to translate very simple words and sentences.

Have you ever used a translation program lately? They tout something like 85 percent accuracy rate, which, if you think of it, would mean mistakes in almost every sentence. The most unexpected outcome is, it can turn a solemn piece of writing into an unintentionally hilarious one.

Take the English phrase "come on". There is no way a program can render it into Chinese with a satisfactory rate of correctness. English language natives may not be aware of it, but the phrase has very subtle changes in meaning, depending on the context, the tone of the speaker and other factors. In Chinese, every one of these possibilities requires a different phrase in translation.

Have you seen Chinese movie subtitles that put "Come on!" for cheering for sports games? It's because one of the dictionary definitions equate it with "Go! Go! Go!" and a computer translator functions very much like a programmer in picking what he sees as the right option.

The beauty of a human language is its ambiguity. Great literature thrives on it. When Hamlet first opens his mouth and out comes, "A little more than kin and less than kind", its meaning can be sensed but not reproduced in another language. You can try, of course, and many have. The pun implies the speaker's intuitive suspicion.

"To be or not to be" uses the simplest of English words, yet the Chinese version has to turn it into "To live or to die", which fails to recapture the elusive dichotomy of deep thinking and simple language.

Chinese, of course, is a rich language equally capable of such linguistic feats, if not more. I'll not quote the great literature of the past but trot out something funny my WeChat friends were posting today. It divides a man's life into four stages, with each one characterized by "xihuan shang yige ren". The six characters, making up four words, are exactly the same, and the trick is in the word shang and the difference in emphasis.

In the first one, it exists to smooth the tone and doesn't need to be translated. So, the phrase means "to like a person".

In stage two of a man's life, shang should be read as a verb, meaning "mount" or more specifically "copulate with".

In phase three, shang is an adjective that means "the last" or "the one before". A manifestation of midlife crisis for Chinese men is to regret that they did not get the woman who waltzed through their life without him realizing she is the one.

For the last stage, shang should be completely de-emphasized while "a" should be turned into "one". So, the sentence becomes "like to be by himself or alone".

I don't think AI can distinguish between the four meanings on paper. Even if they're read out aloud, it could be hard because some of them sound exactly alike. Next time we test an AI program, don't go for the brainy stuff. Pick something like a tongue-twister or a pun or an advertising slogan. Or have it translate a poem, which I consider the ultimate trial.

It's wonderful that machines can do more, but machines are made by man and there are creative jobs that only man can perform. Often the deceptively simple ones. For all that I know, AI may not measure up to a pet when it comes to emotionally connecting with humans.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 03/25/2016 page22)

Today's Top News

- Sanctions show China's resolve to safeguard its sovereignty and territorial integrity

- China OKs three action plans to build pilot zones for a Beautiful China

- CPC leadership meeting stresses steadfast implementation of eight-point decision on improving conduct

- China launches steps against US defense firms, individuals

- Militarism revival efforts criticized

- Leadership highlights Party conduct