Exhibition recalls brutality of POW camp

Photographs and diaries that capture life in Northeast China during WWII go on show in Liverpool

The last thing you might expect when you are suffering under the brutality of a Japanese prisoner of war camp is a cheerful Christmas card from the management of the engineering factory you are being forced to work in.

Yet that was what happened to Gunner Ronald Joy in Mukden Camp in the winter of 1944.

| Alan Joy, son of Ronald Joy, a former prisoner in Mukden Camp, spoke at the launch ceremony of the POW camp exhibition in Liverpool on Nov 6. He holds an engraved mess tin his father made as a tribute to his murdered comrades. Ma Chi / China Daily |

| From left: Visitors at a special exhibition on Shenyang World War II Allied Prisoners Camp in Liverpool on Nov 6; The Christmas card sent by the factory management to Ronald Joy in 1944. |

The management of the Mashu Kosaku Kikai Kabushiki Kaisha factory sent all the workers a card that read: "Wishing you a merry Christmas and a happier new year."

Roy's son, Alan, still finds it a little bizarre 71 years later. He says: "It's as if they knew the war wasn't going to end well for the Japanese."

The card was among artifacts presented to Shenyang World War II Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum for an exhibition about the camp, which was opened at St. George's Hall in Liverpool on Nov 6 by Shen Beili, a minister at the Chinese embassy in London.

The free exhibition, Forgotten Camp, is supported by the Chinese embassy, the Shenyang government, Liverpool City Council and China Daily.

Ronald Joy, who died aged 59 in 1979, was newly married and barely 20 years old when he was sent as part of a Royal Artillery unit to what was then the British colony of Malaya. He and his colleagues were taken prisoner in Singapore when Lieutenant General Arthur Percival surrendered to the invading Japanese forces in 1942.

Selected by the Japanese because of his engineering background, Joy was shipped to Mukden Camp in Manchuria (an occupied area of Northeast China) and put to work in a factory.

Life was brutal. He told his son of one instance when he suffered physical abuse at the hands of the Japanese guards, when he was ordered to do 100 press-ups for some minor infringement of camp rules.

"Each time he pushed up a guard would hit him on the head with a rifle butt. His arms were useless for days afterward," Alan Joy says.

His father also told him about two prisoners who were recaptured after escaping from the camp. They were first paraded in front of the other inmates and then bayoneted to death. "My father engraved a mess tin as a memorial," he says.

The former POW spoke little about his experiences at Mukden Camp, but his son says the family knew he had suffered. Like many other inmates, the soldier experienced the harsh winters prevalent in that part of China. He contracted frostbite and "it used to recur during winter back here in England", Alan Joy says. "He had nightmares. We all knew he was having a hard time."

After the camp was liberated in 1945, Ronald Joy was shipped home via Canada and resumed life with his family - he and his wife had three children - and resumed his engineering career in his native Bradford.

After invading China in 1931, the Japanese set up what it called the "independent state of Manchukuo" under the puppet emperor Pu Yi, the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

The Mukden Camp, along with nearby satellite camps, were designed to hold United States military personnel captured during its invasion of the Philippines, as well as British servicemen held after Singapore capitulated in 1942. Among them were so-called VIP prisoners such as General James Wainwright, who had led American troops in the Philippines, and Lieutenant General Percival.

Mukden Camp, later renamed Shenyang Camp, contained more than 2,000 US, British, Australian, Canadian, French and Dutch servicemen, and is the best preserved of the almost 200 POW camps established by the Japanese throughout Asia.

Reviled by the occupation soldiers, Chinese civilians risked death to pass what little food they could spare to the starving prisoners inside the camps, according to official Allied records based on interviews immediately after the liberation.

Ronald Joy told his son of acts of friendship from Chinese civilians outside the camp, who would smuggle food and medicine through the wire. During the early part of his captivity in Malaya, he and his fellow prisoners would go on work parties and were able to slip into a nearby village where Chinese women hid them in a temple and brought them food. Several times they were able to smuggle food back to where they were being held captive.

The Japanese treated their captives appallingly by any standards. The militarists who gained control of Japanese society before World War II doctored the bushido, the so-called warrior code, to suit their view, which dictated that soldiers who surrendered were less than human. This view extended to Chinese civilians under their control.

After liberation, many prisoners sought out the Chinese who had helped them and stayed in touch until it was no longer possible to do so.

Beatings, executions and solitary confinement made up everyday life for prisoners in the camps, where rations issued by the Japanese were barely enough to keep them alive. They were denied all but the most basic form of medical treatment.

Figures compiled after the war tell a grim story. Less than 3 percent of Allied prisoners held in Nazi German camps in Europe died. In the Japanese camps it was a different story: 37.3 percent of the Allied prisoners they held died, not to mention the tens of thousands of citizens in China, Malaya, Singapore, the Philippines and other occupied nations who were killed as the Japanese tried to implement their vision of a Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

US teams who parachuted into Mukden after the Japanese surrender in 1945 found 1,600 prisoners who were malnourished and emaciated. The Japanese guards had withheld vital International Red Cross supplies for three and a half years.

General Wainwright, who after being freed was flown directly to the Philippines to meet Allied commander General Douglas MacArthur, was "haggard and aged", according to MacArthur's memoir.

"He walked with difficulty and with the help of a cane," he wrote. "His eyes were sunken and there were pits in his cheeks. His hair was snow white, and his skin looked like old shoe leather. He made a brave effort to smile as I took him in my arms, but his voice wouldn't come.

"For three years he had imagined himself in disgrace for having surrendered. He believed he would never again be given an active command. This shocked me. 'Why, Jim?' I said. 'Your old corps is yours whenever you want it.'"

The Japanese destroyed many records of the camps before their surrender, so it is difficult to know exactly how many died from maltreatment, inadequate medical assistance or execution.

As a memorial, the Chinese authorities constructed the museum on the site of Mukden Camp. Some of the buildings were preserved, along with artifacts, photographs and prisoners' diaries. Former inmates have returned to visit the camp over the years, and there is a plaque detailing the friendship between prisoners and the Chinese civilians who tried to help them.

Forgotten Camp, part of commemorations for the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II and the China-UK Year of Cultural Exchange, was to run in Liverpool until Nov 15 before touring France, the Netherlands and the US.

chris@mail.chinadailyuk.com

(China Daily European Weekly 11/13/2015 page30)

Today's Top News

- China to beef up personal data protection in internet applications

- Beijing and Dar es Salaam to revitalize Tanzania-Zambia Railway

- 'Kill Line' the hidden rule of American governance

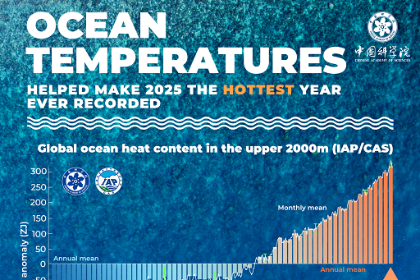

- Warming of oceans still sets records

- PBOC vows readiness on policy tools

- Investment boosts water management